The battle between minimalist and maximalist fashion has reached a new equilibrium

Maximalism’s reign over the past several years of fashion looks to be nearing its end.

Maximalism’s reign over the past several years of fashion looks to be nearing its end.

The splashy, ornate style rose to prominence around 2015, the year Gucci designer Alessandro Michele debuted a weird, gawky new look brimming with prints, frills, and colors. Streetwear was exploding, boosting designer labels such as Off-White and helping infect luxury with a taste for bold, unmissable logos. Demna Gvasalia became creative chief of Balenciaga, where he would introduce his indulgent proportions, as in his triple-soled Triple S sneakers.

But in 2019, growth at luxury labels selling refined, understated minimalism caught up to the maximalists, according to the latest luxury study from management consulting firm Bain & Company. The study doesn’t mention any brands by name and the firm declined to offer any. But fashion companies peddling pared-down design such as The Row (paywall) keep quietly attracting customers, while the breakout brand of 2019 was Bottega Veneta, whose new artistic director, Daniel Lee, has offered an elegant but austere new vision for the label. Federica Levato, a Bain partner and co-author of its report, says formalwear brands by nature also fall in the minimalist category.

This new equilibrium may be more significant than just signaling a swing in fashion’s pendulum. Bain says it suggests shoppers aren’t conforming to trends as they once did, instead picking freely from what’s available to express their own styles.

Minimalism and maximalism have been in a long tug of war. In a recent exhibit on the subject, the museum at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology noted “every fashion movement is a response to what came before it, perpetuating a design cycle that alternates between exuberant and restrained.”

It’s not always easy to categorize designers neatly into one camp or another. The styles are also more complex than just fashion’s equivalents of subtraction and addition. Minimalism rethinks clothing’s construction and the space between clothes and body. Maximalism juxtaposes visual elements to synthesize them into something new. That said, the resulting clothes do tend to strip away elements or pile them on, and there always seem to be designers strongly in one camp or the other who lead the way and set the tone for a period, such as minimalist Phoebe Philo at Celine in the late 2000s or Michele more recently.

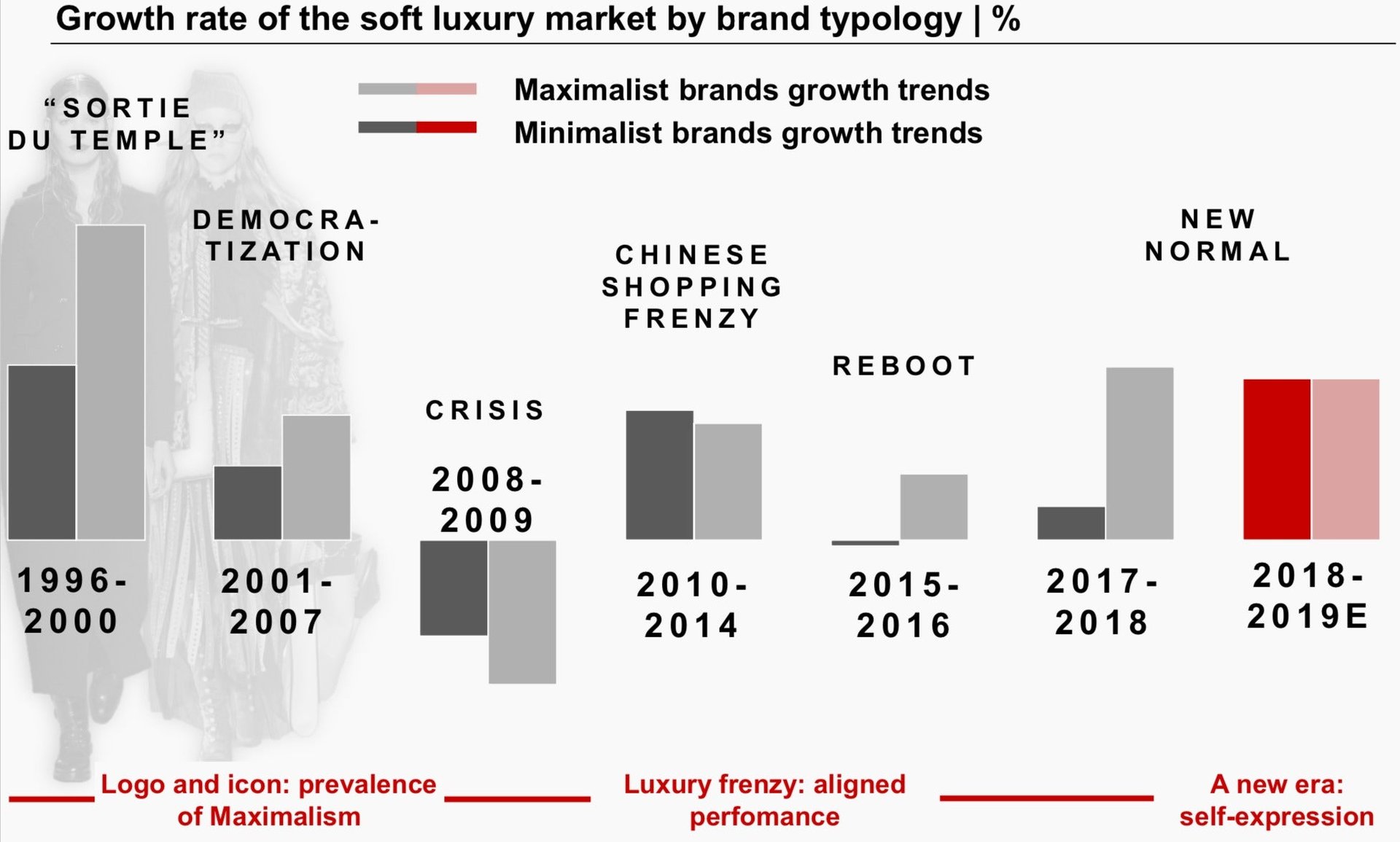

From the mid-1990s through 2000, maximalism commanded the cycle, according to Bain’s data, which charted the performance of each style during different periods of growth for the overall luxury industry. It calls the period “sortie du temple,” or exit from the temple, a time when luxury companies began introducing lower-priced lines and opening up to a mass audience. Logo items were popular, Levato says, as a way “to show the aspiration of the customer.” The same continued from 2001 to 2007, during what Bain calls “democratization,” when luxury companies expanded around the world.

When the financial crisis hit, minimalism suffered less. Shoppers viewed their purchases as investments and avoided items that might lose cachet with a shift in trends, Levato explains. The period from 2010 to 2014 saw maximalism and minimalism growing about equally as a flood of new Chinese customers boosted labels across luxury.

But maximalism took over as Chinese spending slowed and luxury entered a new normal of lower overall growth. The reason, Levato says, is because the brands understood better what customers wanted. They had adjusted their messaging to talk less about craftsmanship and heritage and more about the values they represent. She calls it the start of a “post-aspirational” era.

The minimalists are now catching up, but maximalism continues to grow. For the moment, neither is clearly dominant.

Historically, the fashion industry tended to dictate what was in style. But various experts, including Bain, note shoppers today are increasingly empowered and just as active in the process. To them, Levato says, “brands are just a means to express their point of view.” Even compared to five years ago, they’re buying a wider array of labels. Fashion giants LVMH and Kering have capitalized by cultivating a wide array of brands with distinct points of view that appeal to different customers.

Like media, fashion it seems is fragmenting in service of a universe of niche audiences. The critic Alexander Fury commented on this point last year when reviewing the spring collections. The season’s fashions, he wrote, “more than in any era in living memory, seem inextricably linked to the times in which we live. They are hysterical, scatterbrained and lunging toward extreme opposites.”