In late April 2019, I found myself standing on the 15-acre floor of the National Rifle Association’s annual convention and gun show, looking at a gel mold that demonstrated what a hollow-point bullet does inside a human body.

The mold showed how the bullet spreads out, tumbles, and explodes. A thumb-sized round turns a liver, a kidney, or a heart into mush. The exit wound is as big as a cantaloupe.

Everywhere I looked, I was surrounded by foot soldiers of the NRA.

A paunchy man walked by wearing a too-tight t-shirt that read, “Ho ho ho, now I have a machine gun.” A man with a Gettysburg beard stood to one side. At the nearby Palmetto State Armory booth, two young men caressed AK-47s on display.

I had gone into the convention hoping to answer my questions about how the NRA, a relatively small organization (representatives claim around 5 million members, but the figures are not confirmed) wields so much power.

In the 2008 case District of Columbia v. Heller, the Supreme Court ruled on an individual right to bear arms rather than a state militia’s right to be equipped. But since the late 1960s, the NRA has blocked gun registration and licensing systems, stymied enforcement of existing laws by hamstringing the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF), and undermined public-health approaches to gun violence.

The NRA is at the heart of an American gun culture that has given rise to a societal tolerance for horrific shootings. Yet in the past two decades, the association has morphed into something even more powerful: a machine for right-wing America.

Members of the NRA may not look like much individually. But under one of the most gifted political organizers in US history, current NRA vice president Wayne LaPierre, they remain core to US president Donald Trump’s re-election campaign, even after a year in which the NRA was rocked by grifting scandals. Militarized and steeped in a hierarchical culture that celebrates violence, NRA-member voters are also likely to quickly support war.

I went into the convention thinking there were two forces at work that can explain the NRA’s power and LaPierre’s longevity: Weaponized right-wing politics, and the gun industry, which provides the bankroll. My hypothesis proved to hold up.

But I also learned that 15 acres of guns is not all about politics. Nor is it all about guns.

Before I went to the convention, I went to the Washington National Cathedral to attend Easter Sunday services. As much as I thought it was important to understand the NRA’s bonds with its members, I was also a little scared. I had procured a big-donor pass to the convention, given to me by Rob Schenck, an evangelical who runs the Dietrich Bonhoeffer Institute. A friend of Schenck’s, reverend Pat Mahoney, would travel with me, “undercover.” We registered under our own names, but we both were going with the aim to observe a culture to which neither of us belong.

For the record, Mahoney, while a singularly brave man, is not great at being undercover. Short, compact, and bearded, he has been arrested more than 100 times all over the world, often when he’s protesting for the rights of persecuted Christians.

“I’m Irish and raised on the Jersey Shore,” he likes to say. “I didn’t have a chance, genetically or environmentally.”

American gun history

Before the event, I did my homework to try to understand the history of the NRA, particularly under LaPierre. I talked with Bill Sisk, a policy scholar at the University of Albany’s Rockefeller College, to help me understand the evolution of the group, which was founded in 1871 to help American Civil War soldiers learn to shoot better. For its first 100 years, it was a pretty standard lobbying group, whose leaders spoke up for the waning number of American gun owners.

In the 1970s, Harlon Carter, a former border patrol chief with a head shaped like a bullet, rose to the top of the NRA. A thug who was convicted of murder as a juvenile and later helped execute the 1954 Operation Wetback, the largest deportation plot in US history, Carter helped devise a decades-long legal strategy that allowed the NRA and its allies to carry a new interpretation of the Second Amendment through the Supreme Court.

In 1987, LaPierre stepped into the public eye with a letter demanding the release of Bernard Goetz, a right-wing vigilante hero who shot four black teen-agers on the New York City subway. In 1991, LaPierre was named NRA leader.

Under him, part of the NRA’s power has come from its ability to maintain an affinity with the violent right wing, from Timothy McVeigh to the Branch Davidians, while still projecting an image as a mainstream organization.

“From my cold, dead hands”

For most of his tenure, LaPierre has had an important ally: an ad firm named Ackerman McQueen.

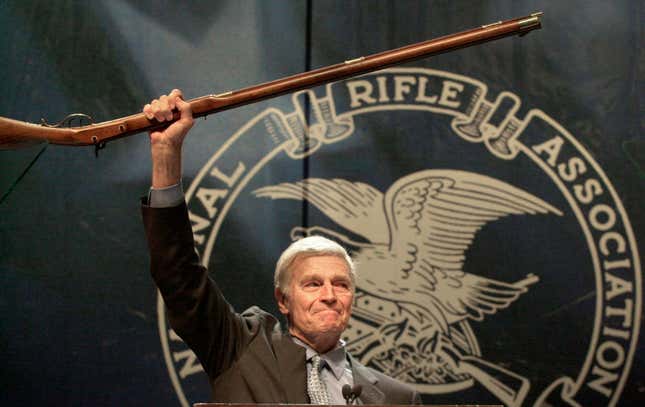

As the 1990s rolled into the 2000s, LaPierre teamed up with the actor Charlton Heston. An aging Moses (the character Heston had played in the 1956 film The Ten Commandments) was the perfect standard-bearer for the newly libertarian NRA, which was as much if not more a platform for the right wing as an advocate for gun rights.

“When loss of liberty is looming as it is now, the siren sounds first in the hearts of freedom’s vanguard,” Heston said in a famous speech as president of the NRA, shaking a replica of a 19th century Sharps rifle above his head. Then, his favorite NRA refrain: “From my cold, dead hands.”

If you watch videos of Heston’s speeches, you’ll usually see the camera panning across a crowd of older white men, their faces shining. Someone was telling them what they wanted to hear as change was overtaking America: They could hold on to their power, and even be “freedom’s vanguard”—if they could only hold on to their guns.

The convention center in Indianapolis, Indiana, one of the few in the country large enough to host the NRA, was decorated with giant banners. Images of three leaders loomed large throughout: LaPierre, his heir apparent Chris Cox, and former security council staff member Oliver North, who fills the public role Heston once held.

North would resign before the weekend was over; Cox would leave over the summer. In times of stress, LaPierre has a history of removing threats, as he had in the late 1990s with one of the original gun rights activistsNeal Knox, who was said to have reservations about the ways the NRA was spending money and ensnaring itself in politics (Knox died in 2005).

After the stop in the convention center, Mahoney and I walked over to the adjacent Lucas Oil Stadium for an evening VIP barbecue. Our big-donor passes meant we were in the “Ring of Freedom,” but there were still some doors closed to us.

I’ve seen this tactic in brokerage and multi-level marketing firms, where the objective is to incentivize people to constantly strive to move up in ranks. The hierarchy suggests there are rewards ahead, but only for select insiders.

And there is always a group of insiders more inside than you.

How guns divide us

“Where are you from?’ I asked a middle-aged couple behind me.

“Northwest Pennsylvania,” the man answered.

“Away from any liberals,” the woman added for context.

A reflexive anti-liberal, pro-conservative stance imbues the NRA. It’s worth remembering that during the Reagan revolution, it was possible to be a conservative Democrat. The US and the NRA have changed in tandem; or, the NRA helped lead the way to a more politically divided country.

Some 97% of the current Republican members of Congress, 242 out of 250, have received money from the NRA, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Its influence is far-reaching, and the connection to guns is sometimes tenuous. Some of the ideas that have shocked mainstream America in the last three years have been relatively out in the open at the NRA for much longer, including racism, misogyny, and nativism.

In 2018, the now-defunct NRATV did a segment in which it dressed the children’s character Thomas the Tank Engine in a Ku Klux Klan hood, as an attempt at satire.

The alternative universe of the NRA

Along with its own language and style, the NRA has its own mythology, which includes, weirdly, an affinity for Big Foot. In the world of the NRA, threats exist to be vanquished by heroes with glorious gunfire. For fun, an imaginary threat works just fine.

This helped explain things when Mahoney and I bumped into a life-sized statue of Big Foot. “I have got to get my picture next to that thing,” he said. We quickly took turns snapping each other and then retreated to the balcony above.

An NRA functionary came to the stage to say grace before dinner.

“I want to pray for the families of …” he began,

“… first responders.”

In the alternative universe created by the NRA, it’s almost as if the innocent victims of gun violence don’t exist. The stories of the rare heroes take up all the airtime.

And the biggest number, the nearly 25,000 people who die by gun suicide in a year, are never mentioned at all.

Mahoney went outside to finish the prayer on his own terms, for his anti-abortion followers on Facebook Live. “I’m at the NRA convention today,” he told me he said. “Let us pray for the victims of gun violence.”

The next morning, we were sitting down to breakfast when a thick-necked security guard approached. “Rev. Mahoney, you’ll have to come with me,” he said, and tossed him out of the convention.

The security guard came back to the table. “Are you with the reverend?” he asked.

I looked up, offering my best suburban mom, stupid-blond smile, and threw Mahoney under the bus. “Not really,” I said cheerfully.

I sat quietly, my blood running cold when I thought about what had happened. What kind of social media surveillance net does the NRA run, to catch Mahoney’s prayer, which was, after all, merely a prayer? And if the allegiance to right-wing values were paramount, wouldn’t his pro-life bona fides count?

Or maybe, what did they not want people to see?

Bringing out the big guns

At breakfast the next day, bigger donors were being inducted into a hall of fame, which involved executives and wealthy families walking to the front to don gold-colored jackets. The companies whose executives were being honored included the historic gun company Mossberg; the big ammunition company Vista, which has lately consolidated many smaller ammunition companies under its umbrella; and the US arm of Brazil-based weapons company Taurus. Taurus is now owned by the ammunitions giant CBC, which produces more than 1.7 billion rounds and owns Magtech USA, which distributes ammo across North America, political expert Robert Muggah later told me. Taurus has also been under investigation for illegal arms trading to factions in the Yemen civil war.

When I started writing about the business of guns, I thought of companies like Colt, Remington, and Glock as gun makers. Now, I think of them as the small arms industry.

Since the end of the Cold War, the small percentage of Americans who are still actively buying guns (and sometimes many guns), are one of their most important markets. There are an estimated 400 million guns in America. Military-style weapons account for about a third of the present-day gun market, and most experts say they are the most profitable third.

“If you go back to a 1960’s gun digest, it was a big catalogue of hunting guns,” Will Vizzard, a former agent of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, and now an emeritus criminal justice professor at California State University in Sacramento, told me later. “But you know the thing with sporting guns? The damn things never wear out.”

According to Vizzard, “Guns used to be tools. Now they’re toys. They’re like Barbie dolls for adult males.”

Arms marketing and advertising 101

You can create a decent sized market for anything if you can convince people they need what you’re selling. Throw some fear into the mix, and the selling gets that much easier.Out on the gun floor, the members were buying AR-15s, which come apart like Legos and have nifty accessories and collectors’ cases. They’re not that effective for hunting, because the caliber they shoot is fairly small, Vizzard told me.

As for self defense? “Maybe if you’re being attacked by a herd of deer,” he said.

In the inner conference room, LaPierre himself moved through the big-donor, small arms crowd, stoop-shouldered, shaking any hand in reach, followed by a man who looked like a bodyguard.

“The media prints all this garbage,” he said, a reference to recent leaks that detailed LaPierre’s $300,000 tab for fine suits and $40 million in payments to Ackerman McQueen in 2017. He laid out the case for NRA as a victim: “Mike Bloomberg and Andrew Cuomo went to every bank and financial services company and said if you do business with the NRA you won’t do business with New York.”

“Some of us in this room … we go back 10, 20 … we go back decades,” he said, putting his hands on the podium and clenching. I took notes on my iPhone.

I made my way alone into the stadium to hear the politicians speak and found a seat behind a group called Bikers for Trump, next to a clean-cut, youngish man and his son. The smell of nacho cheese trays wafted through the air. The lights were tinged red, for patriotic blood, I guess.

The NRA is known for its messaging expertise, which, advertising experts say, likely is based on sophisticated algorithms that tee up images most likely to provoke fear among the target audience of aging white men. Strong women, like Hillary Clinton, and people of color, like Cory Booker, feature often as villains and threats. At the Lucas Oil Stadium, vice president Mike Pence was introduced as “the man you want your daughter to intern for,” before Trump was introduced as “the man you want your son to intern for.”

The messaging was a masterful show of discriminatory efficiency: On one hand, mocking those sexual assault allegations in Trump’s record was an insider’s joke, a way of minimizing the ideals of people in the center and left. At the same time, the mockery appealed to people who love Trump as a man’s man.

The man next to me could hardly contain his excitement, his mouth curling into a downward grimace as he pulled out his camera while Trump took to the stage.

The cruel tone of the president’s speeches has been noted, as was how the NRA audience was excited by his references to violence and cruelty. They cheered when Trump described immigrants who wanted to be Americans being turned away. They cheered when Trump suggested, in the midst of evidence of unprovoked police shootings of black men, that police should be above the law.

“You got to let law enforcement do what they have to do. They’ll solve the problem very quickly. Very quickly.”

They cheered when Trump was cruel to the crowd itself. “Can you imagine having some nice, boring person get up here? Well, they wouldn’t be up here. They would be as far away from you as possible,” he said.

Almost unnoticed by the crowd was the bone Trump threw to LaPierre: Rescinding America’s signature on the UN Arms Trade Treaty.

Withdrawing America’s support makes it easier for big arms companies to trade with impunity. “I see a couple of very happy faces from the NRA over there,” he said, glancing slyly to the other side of the stage.

My last major stop was the NRA member’s meeting. In the wake of grifting scandals, a handful of NRA members stood up to challenge LaPierre. The majority stuck with him, as did the 70-plus member board of directors.

“We’ve got the best,” murmured one member sitting next to me. “Gotta pay him that way.” I sat between two elderly men who argued over which one of them got to talk to me. “We just got her,” one told the other. When the room got remarkably cold, as the executives were trying to end the debate, one of them offered me his jacket.

As I left the room, the recording I’d made of the proceedings disappeared from my phone.

On Sunday, I walked to one of the adjacent hotels. The car bay was filled with black SUVs, their windows tinted. I passed a man wearing an Israeli flag lapel pin, and sat down at the hotel bar next to someone speaking Russian on the phone.

A young man around the corner from me confided he was saving money to buy his 10th machine gun—this time, a belt-fed one. He thought he might need it if the US Army became a tool of an authoritarian regime. He was aggravated that there was a waiting period.

He was the father of two children. If they’re anything like my kids, they worry about school shooters. Our gun laws, I pointed out, enable patriots like himself to arm themselves, but also allow a small number of crazy people to buy weapons. I asked: Did he think, like Joe the Plumber: “Your dead kids don’t trump my constitutional rights?”

He said he understood Joe’s point of view. But then he relaxed for a minute, and said he’d be open to a compromise that would allow him to go through a one-time thorough background check—the kind of licensing process the NRA has opposed—if it meant he didn’t need to fill out the paperwork every time. He thanked me for my respectful questions, and we agreed that keeping the lines of communication open was vital.

I think he knew I was a reporter. We are who we are. In a pluralistic nation, we just have to live together.

The real target

Of course, as a reporter, you think about what’s happening off your notebook pages. At the NRA convention, the real story wasn’t about laws, or politics, or small arms being bought and sold. It was about the America that is being destroyed from the inside out.

The real story to me is the war we’re living at home, holed up in our houses, buying guns and tweeting rapid-fire nastiness, manipulated by dollar-hungry executives into feeding them with our fear and anger.

It’s the tragedy Dwight Eisenhower described in his 1953 address to the American Society of Newspaper Editors, reinvented at an individual level for the 21st century:

“Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children. […]

This, I repeat, is the best way of life to be found on the road the world has been taking. This is not a way of life at all, in any true sense. Under the cloud of threatening war, it is humanity hanging from a cross of iron.”

Leave it to a general to understand the price we pay when we allow our fear to dominate us into a culture of defensiveness.