The transformation of China’s top memes over a decade reflects Beijing’s tighter grip on speech

China’s internet users, like those everywhere, find creative ways to express their anxieties or hopes about life online. But over the years, these popular shared forms of self-expression have become far less critical of the authorities than they used to be—yet another sign of Beijing’s tighter grip on online speech.

China’s internet users, like those everywhere, find creative ways to express their anxieties or hopes about life online. But over the years, these popular shared forms of self-expression have become far less critical of the authorities than they used to be—yet another sign of Beijing’s tighter grip on online speech.

Since 2007, Shanghai-based Yaowen Jiaozi, a literary magazine that focuses on correcting common linguistic errors, has been publishing an influential list of the country’s top 10 buzzwords. The list makes headlines every year, and has been seen as a gauge of public sentiment—even though it does exclude popular words that it deems vulgar.

While the list used to include memes that directly criticized the authorities, it has become both more apolitical and patriotic in recent years. The transformation of the list has coincided with China’s deteriorating environment for civic rights and online speech. In 2008, the year Beijing hosted the Olympics, the government unblocked some banned websites and even designated areas for people to protest during the games, leading to hopes that China would embrace further liberalization. But just the following year, as the western Xinjiang region saw deadly protests, Beijing cut off the internet there for 10 months.

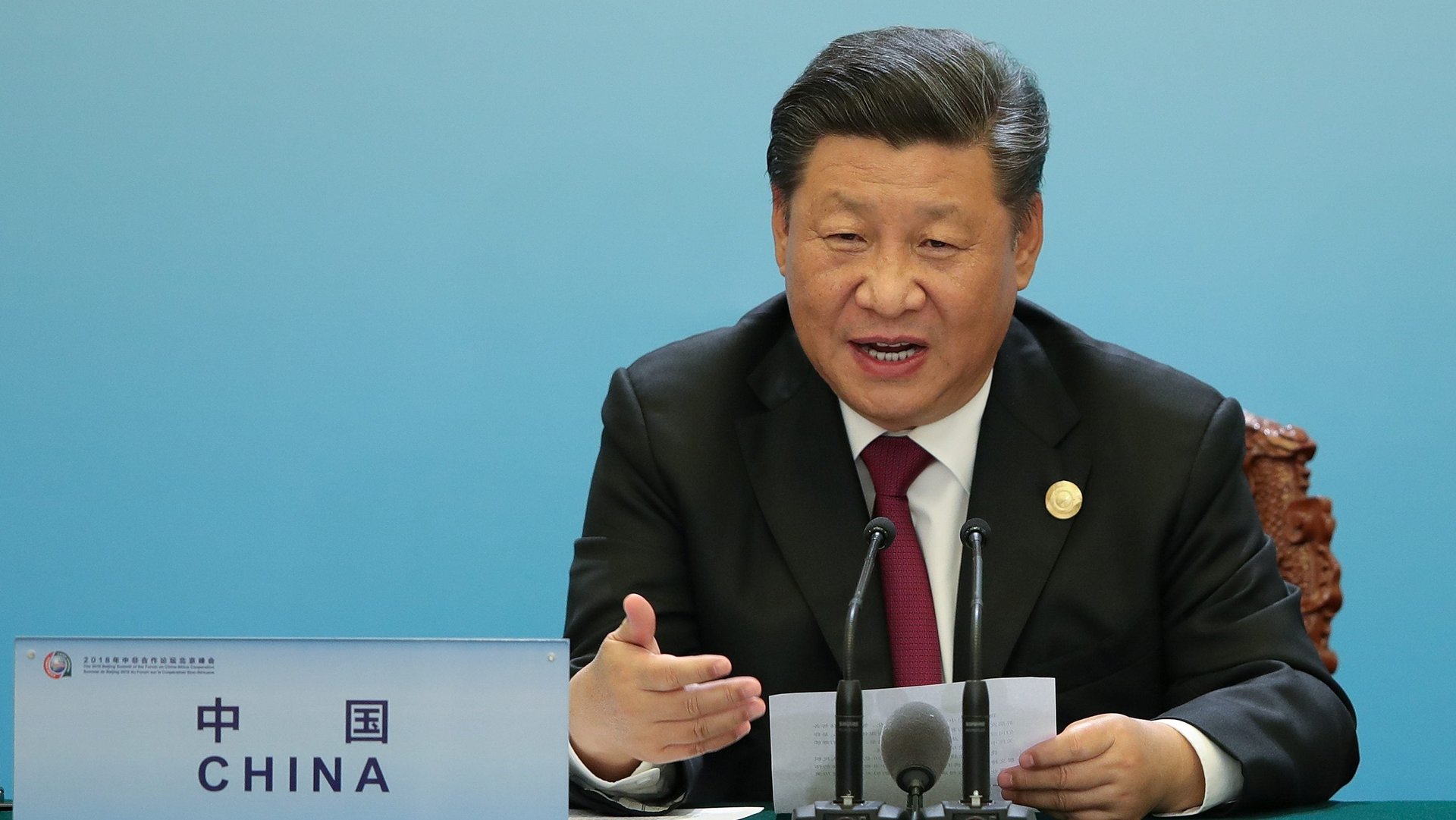

Under president Xi Jinping, who reached the top rung of the Communist Party in 2012, efforts to control the internet deepened. In 2013, for example, China criminalized sharing “online rumors,” an allegation that has been used often against journalists and dissidents. In addition, a mix of human and automated censorship means China is able to efficiently scrub the web of unwanted news and discussions.

Yaowen Jiaozi said (link in Chinese) that in choosing the 2019 words it aimed to promote “positive energy,” a Communist Party concept that informs the control of information.

2009

Hide-and-seek

This meme was inspired by the widely reported death in February that year of a 24-year-old man in southwestern Yunnan province from brain injuries that he sustained while in police custody. The police said that the man, who had been arrested for illegal logging, died after running into a wall while playing hide-and-seek with some of his cellmates. This bizarre explanation drew a huge backlash online.

The local government tried to contain the outcry by inviting some bloggers and others to form an independent investigation committee. Eventually, the local police issued a statement admitting that the man died of physical abuse from his cellmates. The term for hide-and-seek—literally, duo maomao (躲猫猫), or “eluding the cat,”—has since been used to describe a situation where someone tries to avoid public scrutiny or hides the facts.

Fishing

The term refers to police entrapment, and gained traction after a district government in Shanghai fined a 19-year-old van driver who gave a lift to a passenger who was actually an agent in a drive against “illegal cab operations” by local transport authorities. To protest his innocence, the driver chopped off one of his fingers—leading to widespread criticism of city authorities, who publicly apologized for behaving improperly. The Communist Party chief for Shanghai also later admitted the entrapment exercise was “totally wrong.”

Unknowingly employed

A university student complained online that he had found himself “unknowingly employed,” when he discovered his school had recorded him as having found a job after graduation, most likely to make its student employment rate appear more attractive. The complaint struck a chord with many other university graduates, who shared similar experiences online. “Unknowingly having done something” soon became a satirical term used in various scenarios, referring to measures adopted by authorities to cover up facts or portray a falsely bright picture.

The most famous variation is probably “unknowingly committing suicide,” which started to trend after Chinese dissident Li Wangyang, who spent more than 22 years in jail for taking part in the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, was found dead in his hospital room in 2012. Given his age and illness, the police claim that he had committed suicide aroused widespread suspicion online.

Ant Tribe

The phrase started to trend after a nonfiction book (link in Chinese) of that name was published in 2009, which described the tough living conditions of many recent Chinese graduates. Despite having good degrees, they could only get low-wage jobs such as selling insurance or waiting at restaurants, and live in shared rooms in city suburbs or in urban villages. The comparison the book made between the students and ants, as insignificant creatures who live in crowded colonies and work hard to survive, struck a chord with readers.

2019

Overall, popular memes in 2019 have become significantly more patriotic compared with 2009.

While several of the 10 words on the 2019 list were critical of the authorities or of social circumstances in China, this year, the list contains no terms that criticize authorities. It also includes a turn-of-phrase used by Chinese president Xi Jinping, while no such official lingo made the list a decade ago. Meanwhile the most negative word on the list—”bully”—refers to the US, over its trade war tactics.

Looking beyond the Yaowen Jiaozi list, the hashtag #The five-star red flag has 1.4 billion protectors# took off in August this year after incidents in which protesters in Hong Kong took down the Chinese national flag from a flagpole, and tossed it into the sea. That prompted people, including a number of Hong Kong celebrities, to declare their loyalty to the flag.

Mutual learning among civilizations

The term, which comes from a speech Xi gave at the United Nations in 2014, has been repeatedly mentioned by the Chinese leader since then. It is listed as the No. 1 meme on the list, although it’s hardly a phrase regular people use in online interactions. The phrase emphasizes the importance of communication between different nations, which carries especial significance for Beijing this year as it is engaged in an ongoing trade war with the US.

Blockchain

This word appeared on the list also because of an association with Xi this year. Despite China’s crackdown on cryptocurrency exchanges two years ago, Beijing gave a strong endorsement to the underlying technology this year, when Xi delivered a market-moving speech about the importance of accelerating blockchain development China.

996

The meme first became popular in March, when a Chinese developer launched the “996, ICU” project on Microsoft’s GitHub code-sharing community. The term refers to a work schedule of 9 am to 9 pm, six days a week common to many firms in China, including in the tech space. The project aimed to catalog companies who demand workers to stick with the 996 schedule, and proposed as a fix requiring companies to agree to an “anti-996 license” to use open-source software.

This rare show of defiance and discontent among Chinese tech workers quickly made headlines across media both in China and overseas, especially after Alibaba’s Jack Ma defended the 996 schedule as a “blessing.” State-run media have carefully distanced (link in Chinese) the government from 996 culture in their reports on worker complaints, spinning it as a failing of private companies who don’t follow government rules on overtime.

My life is so difficult

This meme comes from an internet celebrity who is popular on Chinese video-streaming app Kuaishou, the rival of TikTok’s Chinese version Douyin. Brother Giao, who is a representative of China’s “village bro” culture that has become popular online, set off this meme in a video in which he was seen frowning and signing deeply while saying this line.

It soon became popular, with a large number of users on Kuaishou and Douyin citing it in their own videos, while users of Chinese social network Weibo also use it frequently to express the feeling of being stressed. However, unlike the critical memes of 2009, the vague lament doesn’t direct blame at any quarter.