This year, Chinese people went collectively mad over a TV show that told the tale of a lowly maid’s ascent to a position of power in the Qing imperial court, as well as a children’s cartoon about a pig, which later drew the ire of the government because it morphed into a “gangster-like” creature on China’s internet.

Despite the ever-tightening environment for free speech, however, Chinese people still found creative ways to express their anger and criticisms over societal problems, such as sexual harassment, and “giant babies” whose selfishness can sometimes lead to disaster.

These were some of 2018’s most popular memes on the Chinese internet. Here are seven of our favorites.

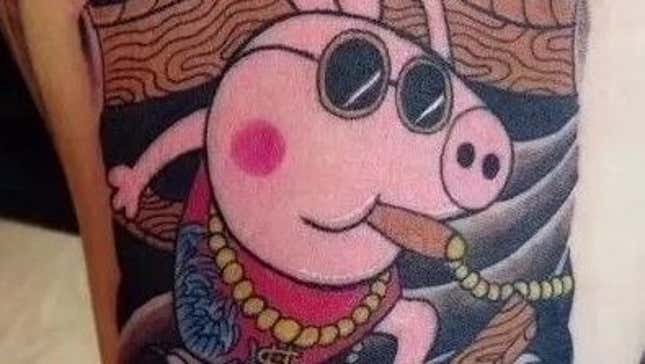

“Gangster” Peppa Pig

Peppa Pig, the British porcine phenomenon that’s taken kids by storm all around the world, was first introduced to China on state broadcaster CCTV in 2015. Peppa, the main character of the show, however, really took off in China last year on live-streaming services such as Douyin (also known as Tik Tok) and Kuaishou. But Peppa’s rise in China also came with a makeover—she became a shehuiren, a slang term for “gangster,” and inadvertently a symbol for those who want to live a life free of constraints and societal pressures.

Tattoos of “gangster” Peppa started to proliferate on Chinese social media, depicting the pig adorning gold necklaces, sunglasses, and tattoos, often with a cigarette in her mouth. The saying “Get your Peppa Pig tatt, shout out to your frat,” also became popular.

Yet Peppa Pig’s rapid rise to fame did not sit well with the government. In mid-April, state-owned newspaper People’s Daily expressed concerns over how “gangster” Peppa could harm children’s health. Later that month, video clips containing the character mysteriously disappeared from Douyin. Though the platform did not clarify reasons for the disappearance, many speculated that Douyin had taken down the videos out of self-censorship. In the same month, state-backed tabloid Global Times said in a report about Peppa’s disappearance that parents and experts in China believe that the pig’s “subversive” imagery could harm “positive societal morale.”

The pig, however, seems to have been fully rehabilitated in China, as videos of the cartoon later reappeared on Douyin and a Peppa Pig movie is scheduled to hit Chinese cinemas in the Lunar New Year.

“Skr”

The Rap of China, a competition for aspiring rappers, was one of the most popular music shows in China last year, and helped bring hip-hop to the mainstream in the country.

Among this year’s biggest internet fads was a catchphrase popularized by one of the show’s judges, Chinese-Canadian rapper Kris Wu, who this year became the first Chinese singer to make the Billboard Hot 100. In one episode, when Wu was asked to predict what would become the buzzword of the season, he replied with “skr” (pronounced as “skirt” without the “t”), a made-up word that Wu often used to praise contestants on the show. He also later made a diss track called “SKR” in response to critics who disparaged his singing.

Internet users now apply the word in different ways. Because skr sounds like 是个 (shì gè) in Chinese, which means “is a,” it can be used, for example, in the following sentence: 你莫不skr傻子吧? (nǐ mò bu shì ge shǎ zi ba), meaning “Are you an idiot?” It’s also a homophone for 死个 (sǐ gè), roughly translating as “freaking out,” so one can say 吓skr人了(xià sǐ gè rén le), meaning “I am freaking out.”

Big pig’s feet

In July, China’s live-streaming service iQiyi began broadcasting The Story of Yanxi Palace, a 70-episode drama set in the Qing dynasty. It tells a story of a clever servant to the queen who enters the royal court in order to try to find out the truth of her sister’s death. The servant, Wei Yingluo, eventually becomes the emperor’s favorite concubine.

The show was a huge success, and was streamed 300 million times a day on platform iQiyi, according to the company. At one point, desperate fans even took to visiting a Vietnamese website that offered episodes not yet available in China—even if it meant that Chinese fans had to acknowledge Vietnamese sovereignty over an island in the South China Sea that’s also claimed by China in order to download the episode.

Wei’s character resonated with Chinese audiences who admired her courage in pursuing love, while keeping a clear head. In one scene where Wei tries to stop another female servant from seducing a guard, she tells her that “those shameless men have human heads that are carrying pigs’ brains.”

In contrast, audiences disliked the role of the emperor, because he went on to enjoy a good life with his concubines after his first queen died.

In Chinese, the word for a male protagonist is 男主角 (nán zhǔ jiǎo), which sounds similar to the word for “men’s pig feet,” or 男猪脚 (nán zhū jiǎo). A coarser phrase meaning “big pig’s feet” (dà zhū tí zǐ) is also used to refer to womanizers or to simply to complain about one’s boyfriend. For example, if a girl tells her boyfriend that she is allergic to flowers but he still buys her a bouquet as a gift, the girl might describe the boyfriend as “big pig’s feet.”

Some have even gone as far as to say that the popularity of the TV show suggests an awakening of female independence in society.

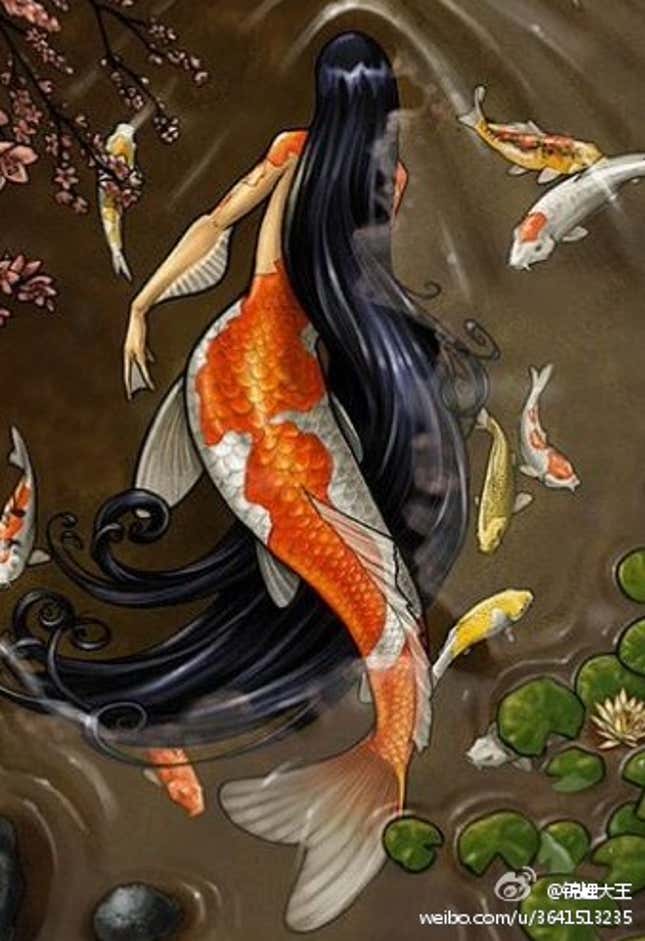

Koi

Koi fish represent good fortune in Chinese culture. In recent years, people have been posting images of koi online as a way to wish people luck.

The fish became really popular this year on China’s internet after Alipay, the payment system owned by Alibaba, rolled out an event called “Chinese Koi Lucky Draw” (link in Chinese) before the week-long National Day holiday in October. The winner was a Beijing-based female computer engineer who beat out 3 million participants to win shopping vouchers and other gifts.

After that, many people started adopting the koi as a symbol for people who have good fortune in their lives.

One example is Yang Chaoyue, a young participant in a talent show called Produce 101 where women are chosen to form a pop group. Although Yang wasn’t particularly outstanding in singing or dancing, she was able to secure a place in the group, making her a koi in the eyes of Chinese viewers. Other koi-like figures include Wei Yingluo, the servant girl in The Story of Yanxi Palace, because of her ability to survive in an imperial court full of scheming women, and Xi Mengyao, the supermodel who tripped in a Victoria’s Secret fashion show late last year in Shanghai, but garnered praise for her calm reaction.

Rice bunny

As the #MeToo movement took off around the world late last year, women in China also began speaking up on social media—but only for a limited time.

Soon after a graduate of a Chinese university spoke about how a professor forced himself on her 13 years ago, many other female university students began posting their stories with the hashtag #MeToo, or its Chinese version #我也是 (wǒ yě shì) on social network Weibo.

That, however, made government officials nervous and censors acted quickly to delete those posts. But Weibo users found ways to work around the censorship. They opted for #米兔 (mǐ tù), a homophone of “me too.” 米 means rice, and 兔 means bunny.

The method has helped keep some posts, and the movement, alive in the country despite severe censorship. The movement even expanded to expose a number of high-profile men in China, including NGO leaders, journalists, the head of one of China’s biggest Buddhist monasteries, and a prominent host on state broadcaster CCTV.

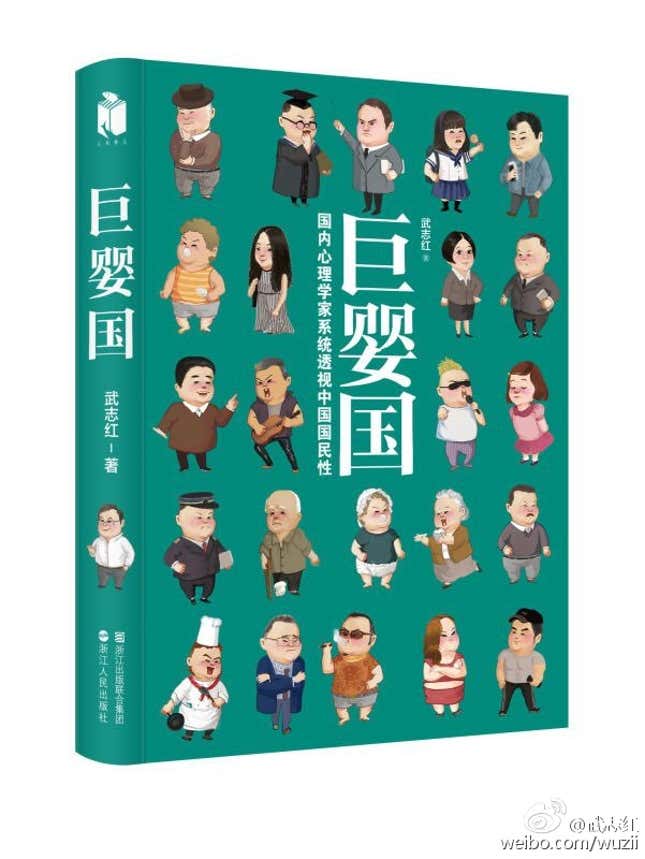

Giant infants

The term first made waves in 2017 when Chinese psychologist and writer Wu Zhihong published a book titled Nation of Giant Infants. In the book, Wu borrows from Sigmund Freud’s ideas of psychosexual development to explain a wide range of social problems in China, including mama’s boys, tensions between mothers and daughters-in-law, and suicides of left-behind rural kids. He claims that the “giant infant dream” is deeply rooted in the Chinese tradition of collectivism and filial piety.

Wu’s book was later pulled from shelves in Chinese bookstores.

Many have applied Wu’s interpretations of societal problems to a series of serious incidents that happened this year. For example, in September, two videos showing train passengers who took the seats of others and then refused to give them back went viral, with people even trying to dox the passengers (link in Chinese). People described (link in Chinese) the passengers as giant infants.

They also used the expression to describe a woman (link in Chinese) who fought with a bus driver after she missed her station in the southwestern city of Chongqing in November. The bus plunged off a bridge and killed 13 out of 15 passengers.

“Eat chicken”

One of the most popular video games in China is PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG), a survival shooter game. Tencent bought the rights to publish the game in China and has launched two mobile versions of it. It’s estimated that more than 75 million players have signed up for the mobile versions.

People in China call the game 吃鸡 (chī jī), or “eat chicken,” because of a message that greets players in the final battle which translates as “Winner, winner, eat chicken tonight.” “Let’s chi ji” therefore doubles up as an invitation to play PUBG.

Despite the booming gaming industry in China, Beijing has been tightening approvals for new game titles in recent months, citing concerns of myopia among China’s youth and violent and sexual content in the games. That’s stalling Tencent’s development of PUBG in the country—it’s still waiting for approval to launch the PC version of the game, and it has yet to receive a license that would allow it to make money from the mobile versions.