Manipulating an election doesn’t necessarily mean seizing control of the nation’s voting machines. Suppressing the vote in targeted geographic areas, while also raising doubts about the legitimacy of the results, could be equally, if not more, effective in flipping an American swing state—and nearly unattributable if done right.

Making it difficult for people to get to polling stations—hacking traffic signals, causing power outages, or disabling a city’s transit system, for instance—is one way for an adversarial intelligence service or non-state actor to keep voters from the leaving home. Mounting a successful disinformation offensive is another.

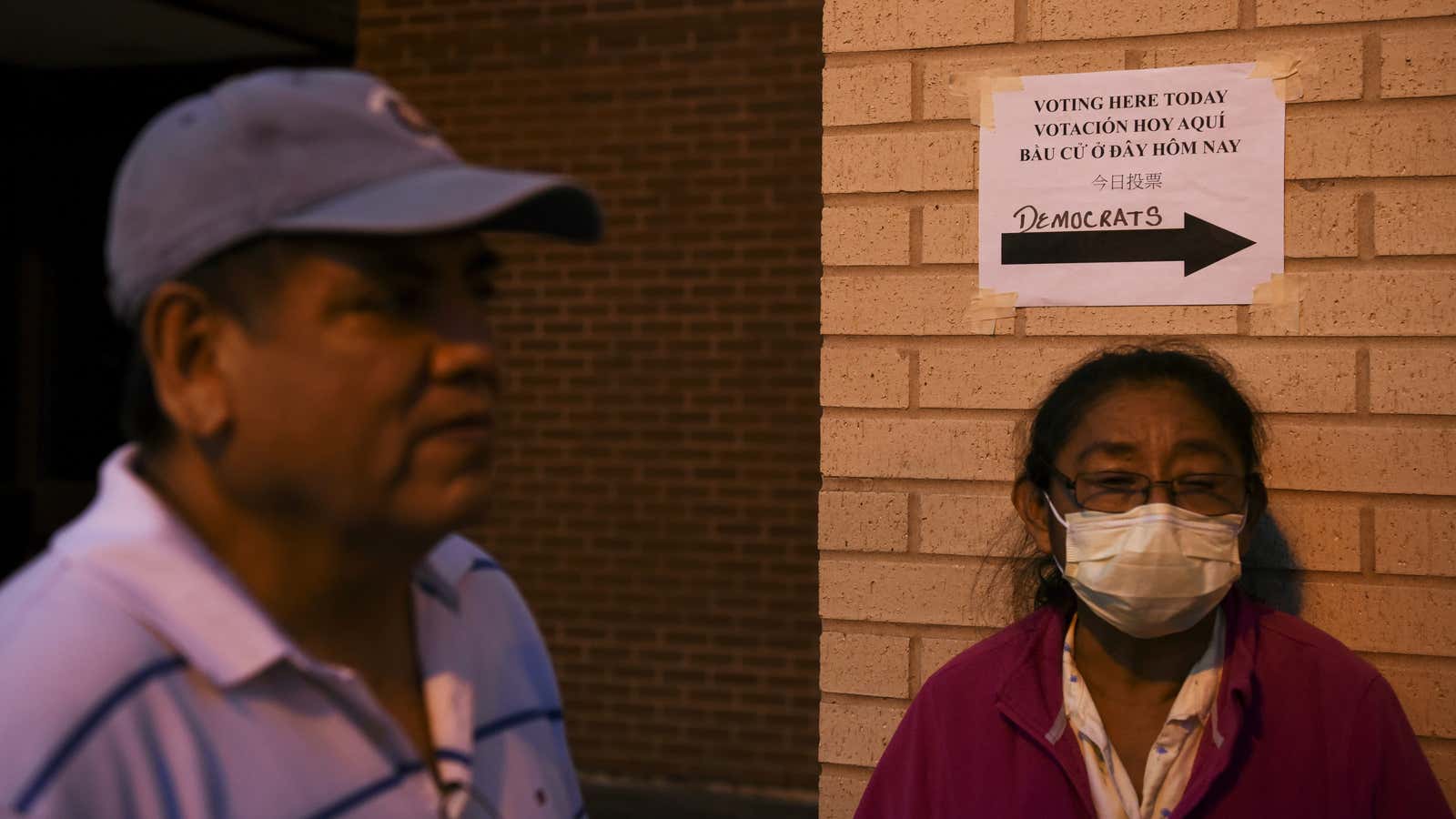

With the spread of coronavirus, there is now a new option for such a campaign. Unfounded concerns over the virus and the disease it causes have already prompted several temporary election clerks in California to stay home on Super Tuesday “for fear of being in public spaces.” Last month, voter turnout for Iran’s parliamentary elections barely broke 40%, the lowest figure since 1979. The reason, said supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, was “negative propaganda” related to coronavirus.

In October, the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security warned that Russia is likely pursuing a voter suppression strategy as a way to interfere with the 2020 presidential election. And officials believe Russian agents are now partly to blame for planting false rumors about coronavirus all over the world.

Philip Reeker, the acting assistant secretary of state for Europe and Eurasia at the State Department, told Agence France-Presse last month that Russia was a leading source of disinformation about the virus in the US.

“Russia’s intent is to sow discord and undermine US institutions and alliances from within, including through covert and coercive malign influence campaigns,” Reeker said. “By spreading disinformation about coronavirus, Russian malign actors are once again choosing to threaten public safety by distracting from the global health response.”

Cybereason, a Boston-based cybersecurity company founded by three former members of the Israeli military’s elite cyberwarfare division, has run a number of simulated election-hacking exercises ahead of the US election in November. The goal of these “war games” is to help law enforcement anticipate and prepare for any and all possible scenarios they might encounter on Election Day.

Sam Curry, Cybereason’s chief security officer, said coronavirus would be “a prime target” for anyone looking to sway the US election through disinformation. “Coronavirus is ammo for propagandists,” he told Quartz.

The World Health Organization, meanwhile, has called the current situation an “infodemic.”

“Through its headquarters in Geneva, its six regional offices and its partners, the organization is working 24 hours a day to identify the most prevalent rumors that can potentially harm the public’s health, such as false prevention measures or cures,” the UN agency said in a press release. “These myths are then refuted with evidence-based information.”