Colombia may be known for growing high-end coffee, but the country is actually pretty fond of the crappy stuff.

Colombian coffee exports reached a record 9.9 million 60-kilo bags in 2013, a near 35% increase from the year prior, according to the Colombian Coffee Growers Federation. And all that extra coffee is of the fancier arabica kind, which isn’t terribly easy to come by these days. In a particularly difficult season for coffee growers in Brazil, Colombia has been happy to help. Colombia is the world’s third largest coffee exporter (behind Brazil and Vietnam), and the largest producer of high quality arabica beans.

Only Colombians don’t appear to have too much of a taste, or budget, for the highest quality beans their country has been growing. They instead have developed an appreciation for milder brews and instant coffee.

“There’s been a lot of innovation in the instant coffee market,” said Luis Fernando Samper, communications and marketing director for the Colombian Coffee Growers Federation, in an interview with Quartz. “It’s especially catering to younger customers.” Instant coffee includes the likes of Nescafe, but also Keurig-like single serving machines and fancier, espresso-like ground mixes.

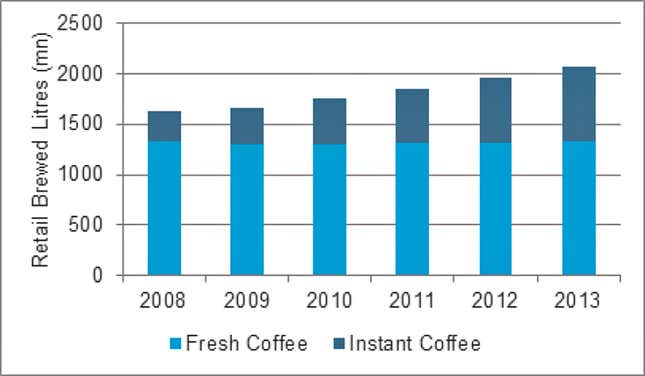

Coffee consumption has steadily increased since 2008 in Colombia, and instant coffee sales have jumped by over 150%, the second largest growth rate in the world, according to Euromonitor. Instant is taking up a larger and larger portion of the local Colombian coffee market.

How come?

Colombia has been producing and exporting heaps of fine coffee for over a century now, but Colombians haven’t historically been able to afford the quality beans they grow. Most of it has been exported to higher income markets, per Euromonitor.

The tale is not unlike quinoa’s in Peru and Bolivia, where farmers have worked to produce more and more of the newly hip grain, which their fellow countrymen can now scarcely afford. The difference, however, is that in Colombia’s case, the inability to afford strong coffee has stoked the appetite for cheaper and weaker stuff. Without the cash to buy the superior coffee being grown locally, Colombians have embraced milder blends.

Higher priced coffee is starting to gain traction, too. “The highest-tier coffees are now growing at six to eight percent,” Samper said. “There’s actually been a little bit of a rebound of roasted coffee.” Colombian coffee chain Juan Valdez, which has almost 200 branches across the country, has played a large part. And Starbucks, which has long been a leading buyer of Colombian coffee, is planning to push it along further by opening 50 stores in Colombia over the next few years.

But there’s reason to believe the fine coffee market still has a fair amount of marketing to do if it wants to overcome the country’s taste for lower quality brews. “No one knows what real coffee is,” Germán Arias, a local coffee shop manger told the New York Times in 2004. Ten years later, given the meteoric rise of instant coffee, that may still be they case.