The Hong Kong Exchange is moving into commodity trading this year to cater to the changing needs of “China Inc.,” the bourse’s exuberant chief executive Charles Li told analysts and reporters in Hong Kong on March 4. “China’s commodity business needs to internationalize and we’ll be here,” he said, with “new products, new members and new partners,” including potential tie-ups with the mainland’s fast-growing commodity trading platforms.

His announcement is the latest sign that after investing heavily around the world to buy and mine the world’s raw materials, China’s next step is to plan an even bigger role in trading them.

The move comes as newly risk-adverse Wall Street banks including JP Morgan Chase, Barclays and Morgan Stanley—licking their wounds from trading losses and daunted by tougher regulations—have been closing or selling their commodity trading units.

Now Chinese, Russian and Middle Eastern firms, particularly state-owned ones, are starting to fill the gap. Chinese banks, including China Merchant Securities, state-owned ICBC, and GF Securities, have been particularly aggressive about expanding into global commodities trading through acquisitions. Bank of China’s commodities group and a unit of Chinese broker GF Securities recently joined the London Metal Exchange, the world’s primary metals trading platform, which was purchased by the Hong Kong Exchange in 2012.

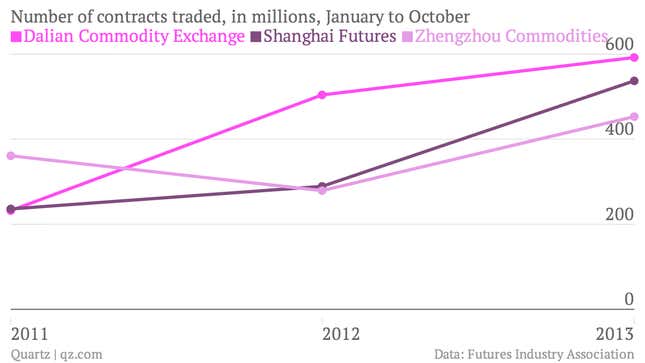

China’s manufacturers and steel companies, which are the world’s largest consumers of many commodities, clearly stand to benefit from the shift. Volume on China’s commodities futures exchanges grew sharply in the past year, after rules governing China’s domestic commodity trading exchanges have slowly been relaxed. Still, trading is off-limits to foreigners without a Chinese partner or local subsidiary. The top three Chinese domestic derivatives exchanges are ranked 11th, 12th and 13th among all global derivative exchanges by volume, according to the most recent Futures Industry Association report. In the second half of this year, the Hong Kong exchange will launch new cash-settled commodities futures contracts including base metals and bulk commodities, a spokesman told Quartz—designed to feed off of strong trading of these goods in Asia. If successful, it would make it easier for commodity buyers and sellers outside of China to gauge demand of their Chinese peers, create a more liquid market and one in which Chinese firms have more influence on global prices.

Plenty of questions remain about China’s domestic commodity trading practices. China’s copper trading, for instance, often seems to bear little relation to global supply and demand, as Quartz has reported, because companies use the metal as collateral to obtain loans for financial speculation. When banks tighten other lending, copper imports increase so that companies can get new copper-backed loans, and then sometimes sell the copper back into the open market without ever having used it.

Li’s enthusiasm and China’s commodity growth aside, Hong Kong’s past forays into commodity trading have not fared well. The Hong Kong Mercantile Exchange, set up with great fanfare in 2008, never attracted the volume of contracts it needed to be a viable exchange, and shut its doors last year.

But now that Wall Street is exiting, there may be plenty of room for the Hong Kong exchange, backed by a growing desire from China’s huge commodity players to join the party.