Cambridge Analytica is the most famous data company associated with President Trump’s online strategy but, according to former staffers, it was not the most influential. “Their whole personality profile turned out to be complete BS,” Matt Braynard, a former data director for Trump’s 2016 campaign, told Quartz. “But HaystaqDNA, however they did it—whether it was black magic or what—was incredibly effective.”

HaystaqDNA claims to hold data on more than half the US population and uses this information to analyze and predict voters’ detailed political opinions. In 2015, it sold some of its data to nonpartisan group L2, according to Politico, which then sold the data onto the 2016 Trump campaign. But while HaystaqDNA said the Trump campaign only had access to limited data, Braynard said this was still hugely influential. “We used their data to determine every door we knocked on, every door we rang, every piece of mail we sent,” said Braynard. “All of our targeting was driven by that data, and it was incredibly reliable.”

Neither HaystaqDNA nor the Trump campaign responded to Quartz’s requests for comment.

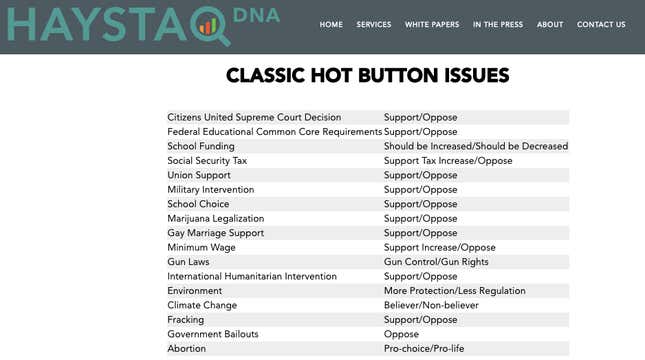

HaystaqDNA was created by former President Obama staffers, and is rooted in progressive politics. It uses data to predict individuals’ opinions on everything from transgender bathroom use to creating pathways to citizenship, and target political messages accordingly. These tactics, which began as a cutting-edge left-wing approach in 2008, made its way across the aisle in the last election, and are now commonplace. In this year’s election campaign, Bernie 2020 spent more than $1.7 million hiring HaystaqDNA for research, digital advertising, and software, according to FEC filings. Senator Bernie Sanders did not respond to Quartz requests for comment.

The use of personal data to target political messages has a nefarious reputation thanks to Cambridge Analytica. But HaystaqDNA’s practices are highly precise, entirely above board, and a standard feature of political campaigning. “We’ve moved into an era where data, lookalike models, and microtargeting have become table stakes for running in an election, and that’s for any election from President to dog-catcher,” David Goldstein, chief executive of political digital consulting firm Tovo Labs told Quartz. HaystaqDNA is no longer being hired by a presidential candidate to create customized models now that Sanders is out of the race. But the company’s methods permeated and inspired political campaign methods across the aisle, and serve as a demonstration of how politicians harness data to reach the public.

What is HaystaqDNA?

The company is led by Ken Strasma, targeting director for President Obama’s 2008 campaign, and uses data to precisely determine political opinions. HaystaqDNA has profiles on millions of voters, and uses data to predict individuals’ views on Black Lives Matter, transgender bathroom use, the border wall with Mexico, a ban on Muslims entering the US, and whether there should be a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, among other issues.

This use of data to analyze political views is commonplace. David Carroll, professor at The New School and expert on online misinformation who successfully demanded Cambridge Analytica hand over the data it held on him under UK data privacy law, said the industry as a whole doesn’t provide access to the data it uses to analyze opinions and target ads. “We don’t have enough visibility to understand it, but it certainly is standard practice,” he said. “To me, standard practice is very concerning.”

Strasma himself acknowledged that political microtargeting can be invasive. “The stuff on the cutting edge straddles the edge between cool and creepy,” Strasma told Wisconsin publication The Capital Times in 2017. “I wouldn’t be surprised if we see more regulation coming in the United States as more people realize how much data is out there about them.”

HaystaqDNA’s collection and use of data is at the forefront of political microtargeting. When the company partnered with Xaxis, a subsidiary of the world’s largest advertising company WPP, to create a political targeting tool in 2015, Xaxis’ then-chief executive Brian Gleason told the Financial Times the partnership would allow “laser-like targeting” of messages to voters. “We haven’t seen anyone else doing [online political targeting] with this level of granularity,” he added.

In 2015, HaystaqDNA claimed to hold data on 166 million US people or half the US population. It has collected significantly more in the years since; their website claims their political data models are linked to 170 million US voters, while a separate white paper on their website claims HaystaqDNA has a consumer file of 260 million adult consumers in the US, including “all of the Personally Identifying Information (PII) as well as over 1200 fields of additional data—Census Data, Property Data, Survey Data, Modeled Data and aggregated data bought from sources like magazines, retailers, airlines, hotels, insurance companies, financial institutions, etc.” To make use of its large dataset, HaystaqDNA surveyed 10,000 people on their political views every two months, according to a 2015 article in the Financial Times, and then used statistical modeling to match the data of those in the 10,000-person database with its dataset of millions.

This practice, known as “lookalike modeling,” is hugely successful in advertising and allows HaystaqDNA to accurately predict how those in its larger database would answer the same questions that were posed to just 10,000. When HaystaqDNA teamed up with Xaxis, the Financial Times reports, it combined these data profiles with individuals’ online IDs using LiveRamp, a company that specializes in matching offline and online identities.

In HaystaqDNA’s work for Sanders in 2016, the company matched HaystaqDNA data with online IDs using digital marketing company Revolution Messaging, according to The Capital Times. HaystaqDNA chief executive Strasma explained that signing up for online services, including news sites, shopping accounts, or bargain-finding websites, can help match HaystaqDNA’s data with an individual’s online identities. “Most people have signed up for at least something,” he told The Capital Times in 2017. “From that moment on, you know that at least in one point in time this particular device was used to sign in for a particular person’s name and that is how the device ID-to-name matches.”

HaystaqDNA creates personalized models for political clients who hire the firm. When it worked with Sanders in 2016, HaystaqDNA ran 50 issue-based models to best identify the voters likely to be persuaded to vote for him, according to The Capital Times. Strasma said these models were matched with Revolution messaging data and could be used to group similar types into pools as small as 20 people.

Why left-wing data was useful to Trump

HaystaqDNA sold its data to nonpartisan data vendor L2, and in 2016 Braynard told Politico that he’d used the data in the Trump campaign. Baynard fell out with the Trump 2016 campaign in the early primaries, but said HaystaqDNA data helped secure Trump’s nomination. His colleague, Witold Chrabaszcz, who also worked on Trump’s 2016 campaign data, said HaystaqDNA data was especially good at identifying likely Trump-supporters who didn’t typically vote. “Having this tool [Haystaq] at our disposal was quite useful. Especially at the early stages of the campaign, we used Haystaq scores quite a bit,” he added.

In 2016, Strasma told Politico that HaystaqDNA only sold its generic models, rather than the customized work it did for Sanders. These generic models were enough, according to Braynard. He first got HaystaqDNA’s data in October 2015 and was able to use it in combination with his own survey of 10,000 people to determine Trump supporters nationwide, he told Quartz. Braynard said he identified a few thousand Trump supporters within his own survey, and then looked at what HaystaqDNA data revealed about those people. For example, HaystaqDNA typically showed that these voters were against transgender use of bathrooms and supported building a wall along the US-Mexico border. “I find that a very high number of them [Trump supporters] correspond to a certain combination of answers on HaystaqDNA’s profile,” he said. And so, rather than doing more surveys to identify likely Trump voters, Braynard said he could simply identify them using only HaystaqDNA’s data on political opinions.

Rather than trying to persuade people to support Trump, the campaign could simply focus on persuading likely Trump supporters who rarely voted to get out and vote. “We put all our effort not into convincing them of anything, but motivating them to turn out,” he added.

Though HaystaqDNA has a reputation as a left-wing firm, Chrabaszcz confirmed that its data was just as useful for right-wing political messaging. “We might target some of the identified groups differently with different messages but if the segments are accurate, they’re just as useful to us,” he said. And while HaystaqDNA’s methods are now standard in political microtargeting, Chrabaszcz said they had superior results. “There’s a lot of very mediocre tools out there and a lot of consultants that promise quite a bit. In this case, you actually have an experienced team that knows what they’re doing,” he said.

What data does HaystaqDNA use?

HaystaqDNA did not respond to Quartz requests for comment on the full data they collect on individuals, but chief executive Strama has previously spoken of the importance of social media data. In 2014, he told CMO by Adobe he was focused on analyzing emotions from tweets and Facebook posts, and matching real-world and online identities. “The real next frontier for us is modeling people who are going to be in the market before they exhibit that shopping behavior,” he said in an interview that has since been taken down, but is available on internet archives. “We want to be able to model who’s about to start shopping for the product and get that ad to them first, when we have an exclusive conversation with them. I would say social media data mining is probably the biggest untapped growth area. A very, very small fraction of the available public information is currently being analyzed.”

Another white paper on HaystaqDNA’s website highlights how the firm couldn’t find a source of data on who owns solar panels, so created their own by hiring Amazon Mechanical Turk workers to trawl satellite photos and flag buildings that had solar panels. Having collected this information from areas in California and Nevada, HaystaqDNA used their data to build a model to predict who is likely to buy a solar panel.

The website for HaystaqDNA highlights how the company helped Bernie Sanders in 2016 by identifying potential hispanic and African-American supporters. “Those groups of voters were often scored low on our support models, but it was important to the campaign to expand its appeal among minority voters, so these models allowed the campaign to find which African-American voters, for example, were relatively more likely to be open to Sanders,” the website reads. “These were used for specific outreach to those groups, to maximize persuasive impact while minimizing the risks of contacting unsupportive voters.”

Politics as normal

While perfectly legal, HaystaqDNA’s collection of data and microtargeting appears to conflict with Sanders’ policy positions on privacy. The Democratic senator repeatedly warns of online privacy invasions contributing to an Orwellian society, and has spoken out at how consumers’ information is collected and sold by private companies specifically.

Yet Bernie Sanders hired HaystaqDNA for his presidential campaign in both 2016 and 2020. The campaign spent this money in a series of 13 payments starting in April 2019, with a final payment of $186,000 in February 2020 bringing the total to $1.7 million. This put HaystaqDNA at number twelve on the list of companies that received the most money from the Sanders 2020 campaign, behind major expenditures such as Blue Cross Blue Shield health insurance, American Express credit card payments, and ADP human resources management software. Though Bernie 2020 spent more money with online-focused organizations that involve data, such as BlueWest Media ad agency, fundraising and strategy consultants Aisle 518 and pollsters Tulchin Research, the campaign spent more with HaystaqDNA than any other big data analytics company.

Such practices are now standard throughout the political sphere. The online targeting available via social media and Google “creates an enormous competitive advantage for whichever candidate can best capitalize on these tools to reach and persuade voters and potential donors,” Tovo Labs chief executive Goldstein told Quartz.

The practice of using data to microtarget political messages has had more sinister associations since Cambridge Analytica’s abuses were revealed, though such methods have influenced politics for more than a decade. A 2013 New York Times article on President Obama’s digital team, including Ken Strasma, detailed how Obama staffers gained data by asking people who signed into the campaign website via Facebook to give the campaign access to friend lists, photos, and news feeds. They then used this information to identify friendships between firm Obama-supporters and those who might be persuadable. This extensive use of data raised concerns inside Facebook. “They’d sigh and say, ‘You can do this as long as you stop doing it on Nov. 7,’” Obama campaign software engineer Will St. Clair told the New York Times in 2013. Facebook told the New York Times the large levels of unusual activity raised warnings, but the campaign didn’t violate its privacy and data standards.

The vast collections of data that warranted little more than a sigh seven years ago are seen as potentially more disturbing today. “This is an unregulated, lawless arena,” Jeffrey Chester, director of the Center for Digital Democracy, told Quartz. “I think 2020 is going to be the dirtiest digital campaign to date. Both sides have amassed a vast amount of data. They’re all pushing the envelope without any real thought about privacy.” HaystaqDNA, the microtargeting company that influenced both Trump’s and Sanders’ campaigns, is well within the law and the norms of political advertising. As they don’t reveal their complete dataset, it’s not clear how they’re so precisely able to evaluate voters’ political opinions. “All I know is that it does work,” Braynard. “It is effective.”