Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, home fitness represented roughly a quarter of the $11.5 billion global fitness equipment market. As millions of people find themselves confined to their homes, they are embracing modes of exercise that have roots that stretch back much further than the exercise tape and home yoga mat.

“Exercise as a deliberate habit of relatively affluent people goes hand-in-hand with the rise of white collar labor and the sedentary work associated with that,” explains Natalia Mehlman Petrzela, an associate professor of history at The New School and author of a forthcoming book about American fitness culture. “As you have more men working at desk jobs and labor-saving devices in the home, you have more cultural pressure to be deliberate about exercise.”

The pandemic has made that even more the case, as large companies and small studios sprint to capture home exercisers. But home fitness didn’t start when we found ourselves desk-bound. Here’s a quick journey through some highlights in home-fitness history.

600 BC: The Indian physician Susruta issues the first known prescription for moderate daily exercise as an antidote to diabetes and obesity, advising patients to walk, run, swim, or play sports until they noticed a “sense of weariness from bodily labor,” according to Charles Tipton, a physiology professor at the University of Arizona. “Diseases fly from the presence of a person, habituated to regular physical exercise,” Susruta wrote, adding that working out also “gives the desirable mental qualities of alertness, retentive memory, and keen intelligence.”

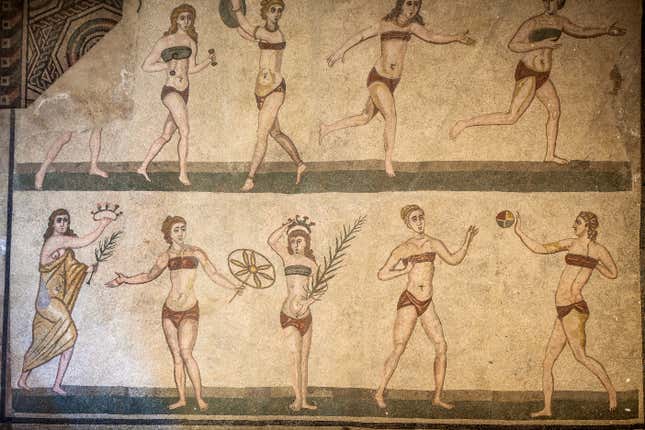

300 AD: A Roman aristocrat adorns his Sicilian villa with mosaics depicting sportswear-clad women throwing discus, running, and playing ball within the privacy of home, at a time when most Roman women had little access to public life. Though they resemble modern-day dumbbells, the pair of weights one figure holds were actually tools to help balance during the long jump.

1450: In a letter to his sons at their university in Toulouse, France, an Iberian physician urges them to work out at home when outdoor exertions aren’t possible. “If you cannot go outside your lodgings, either because the weather does not permit or it is raining, climb the stairs rapidly three or four times, and have in your room a big heavy stick like a sword and wield it now with one hand, now with the other, as if in a scrimmage, until you are almost winded,” he wrote, in a letter discovered inside a 15th century manuscript in France. “Jumping is a similar exercise.”

1796: Francis Lowndes, a London-based “medical electrician,” is awarded a patent “for a new-invented Machine for exercising the Joints and Muscles of the Human Body.” He calls his prototypical home exercise machine the Gymnasticon.

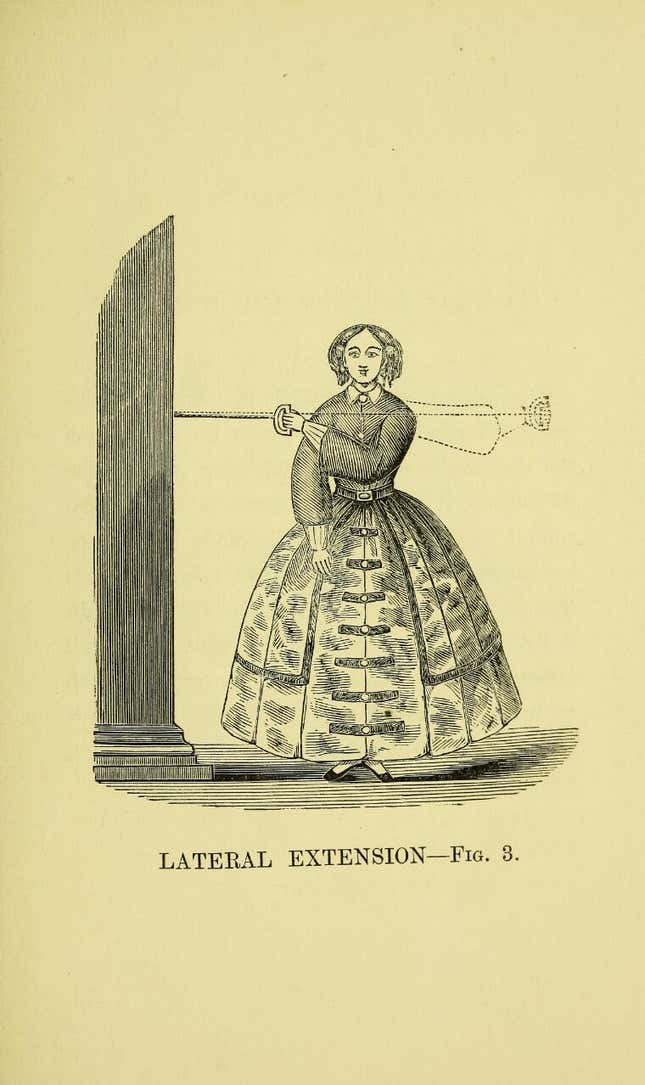

1861: As the Industrial Revolution takes off, an increasingly sedentary elite must seek out exercise intentionally. London-based Gustav Ernst, who describes himself as an “orthopedic, anatomical, and gymnastic machinist,” invents a portable home gym so that Victorians can exercise in private (and in full evening dress, according to the illustrated manual).

1890: Vigor’s “Horse-Action Saddle” promises users the health benefits of horse riding without the messy inconvenience of leaving the house or owning an actual horse. “It is good for the figure, good for the complexion, and especially good for the health,” claim its advertisements, which also features endorsements from the Princess of Wales, the Countess of Aberdeen, and one Dr. George Fleming.

1897: “The Rambler” magazine publishes an article about an avid cyclist who rigs up a bicycle-treadmill combination that allows him to enjoy his favorite sport at home on rainy days. A painter of signs by profession, the man equips his rudimentary home stationary bike with a rolling backdrop to mimic the effect of passing scenery.

1922: A Chicago entrepreneur named Wallace Rogerson records a phonograph album called “Get Thin to Music” that talks listeners through a series of home exercises. Exercise records and radio programs are popular with urbanites for whom “the idea of interacting with the technology of the day is interesting to them, just as it is to us,” says Jan Todd, a professor of kinesiology and health education at the University of Texas at Austin whose books include Strength Coaching in America: A History of the Innovation That Transformed Sports. (Todd is also a former powerlifter named the world’s strongest woman by Sports Illustrated during her record-breaking career.)

1929: Bodybuilder Charles Atlas and a business partner create a mail-order home exercise course called “Dynamic Tension” whose comic-strip style ads (“Hey Skinny!”) are a magazine fixture through the 1940s. Film, mass media, and a burgeoning celebrity culture for the first time allow regular people the opportunity to unfavorably compare their own physical appearances to those of wealthy strangers. A surge of interest ensues in “slenderizing” (for women) and bodybuilding (for men).

1948: Cleveland’s WEWS television station hires a television personality named Paige Palmer to host a daily fitness television show, the first of its kind in the nation. Clad in a leotard and black fishnet tights, Palmer leads viewers through exercise and lectures on fitness, fashion and nutrition. “The Jack LaLanne Show,” the first nationally syndicated workout program in the US, premieres three years later.

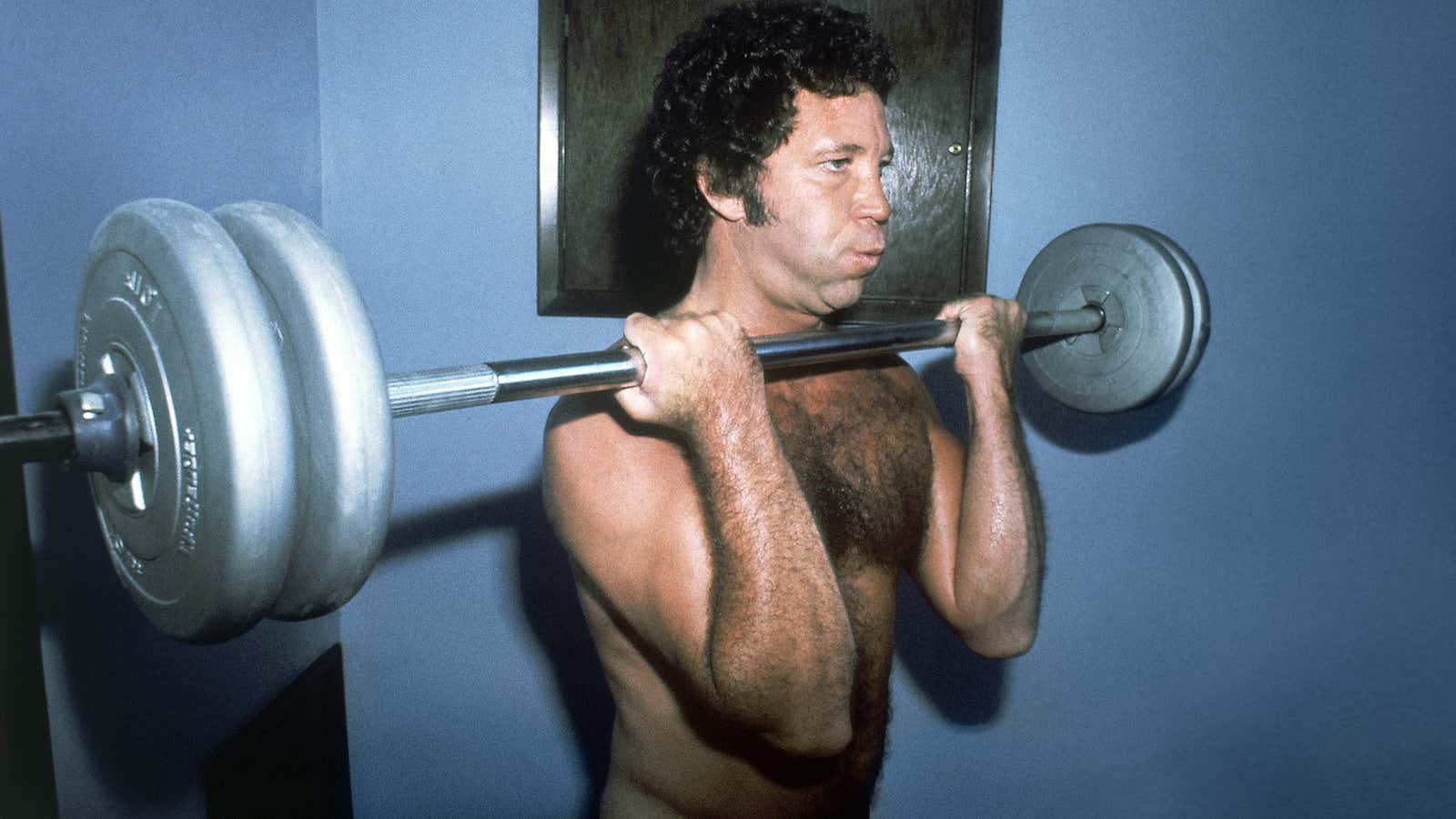

1977: The Video Home System (VHS) recording device debuts in the US. Gyms to this point have been primarily focused on bodybuilding, and are “not necessarily turf that women were comfortable walking into on their own,” says Todd. The rise of the VHS workout makes it easier for women to exercise in the privacy of home. In 1982, the actress Jane Fonda releases “Jane Fonda’s Workout,” which goes on to sell 17 million copies and become the bestselling VHS tape of all time.

1984: The U.S. Federal Communications Commission lifts regulations on ad length, and the infomercial is born. The medium thrives on self-improvement products, including home fitness gear like the Thighmaster (slogan: “We may not have been born with great legs, but now we can look like we were.”)

1996: Total Gym, a home fitness contraption endorsed by Chuck Norris and model Christie Brinkley, airs its first infomercial and goes on to sell 4 million units.

2005: YouTube launches, and shortly thereafter so do the first YouTube workout videos. YouTube allows yoga teachers and fitness instructors to gain millions-strong global followings, without either student or teacher ever having to leave home.

2013: A successful Kickstarter campaign launches Peloton, a stationary bike system that lets users follow along with classes streamed directly to the bike. The company has since sold 577,000 bikes and treadmills. The following year, Fitbit announces an app and website for its wearable fitness trackers that let users sync them to phones and other devices.

“Home fitness has long had a commercial element in that we’d buy exercise videos, workout clothes, and so on,” says Brad Millington, a senior Lecturer in the Department for Health at the University of Bath. “But now the very act of partaking in fitness might have value through the data we produce.”