When a central bank cuts interest rates as low as they’ll go and the economy still doesn’t respond, it needs to devise more creative ways to revive it. When rates are at or near zero, so-called “forward guidance” is as good as extra stimulus, the theory goes, because central banks can use it to commit to keeping rates low for a certain period of time, or until certain economic conditions are met. Markets can then trade with greater confidence, given that the ground rules for rate hikes are spelled out in black and white.

But the experience with forward guidance has rarely been as smooth in practice as in theory. The Bank of England, for example, recently revised its rules for hiking rates only six months after first unveiling its forward-guidance policy, making them more vague and complicated. The rationale seems to be that traders were getting the wrong idea about when the bank would tighten its policy under the simpler guidance policy.

So is forward guidance worthless, or even counterproductive? Not necessarily, according to new research from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). In studying different periods in the euro zone, Japan, the UK, and the US, the BIS found that the volatility of one-year interest rate futures was lower after banks gave forward guidance. But that is not true for longer-term instruments. And evidence was inconclusive that guidance decisively lowered interest-rate expectations or more closely tied rate expectations to the economic indicators a central bank was saying it relied on. In short, there is a lukewarm case in favor of forward guidance.

Why bother, then, if guidance also serves to very publicly highlight how bad central banks are at forecasting? In part, because this ineptitude isn’t news.

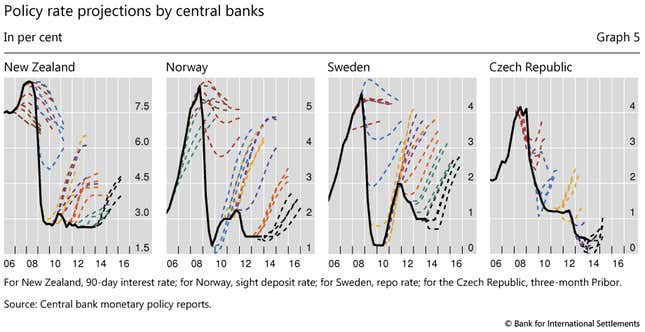

A few central banks issue specific forecasts of where they think the interest rates they control will go in the years ahead, instead of setting timelines or triggers related to inflation or unemployment rates. These banks—in the Czech Republic, New Zealand, Norway, and Sweden—make uniformly rubbish predictions, as detailed in the rather embarrassing chart below. (Actual rates are the black solid lines, and the banks’ forecasts are the colored dotted lines.)

Despite consistently overestimating the path of interest rates, this “seems not to have had any major effect on central banks’ reputation or credibility,” the BIS researchers conclude. After all, central banks are hardly alone in making duff economic forecasts, so it’s not as if their predictions—for interest rates, economic growth, inflation, or any other indicator—are worse than anybody else’s.

Forward guidance, then, represents good value for the effort involved, which is essentially publishing more detailed economic forecasts and issuing longer statements at press conferences. Compared with other “unconventional” monetary stimulus measures, like quantitative easing, which has seen central banks’ balance sheets balloon as they spend trillions of dollars buying bonds, the embarrassment of making a bad prediction is worth it if it brings a benefit, however small.