The Irish have been in a good mood lately. Unemployment, though still high, is falling. The country managed to “exit” its bailout agreement. In fact, by some measures, Irish consumer sentiment is as good as it was during the best of the pre-crisis boom.

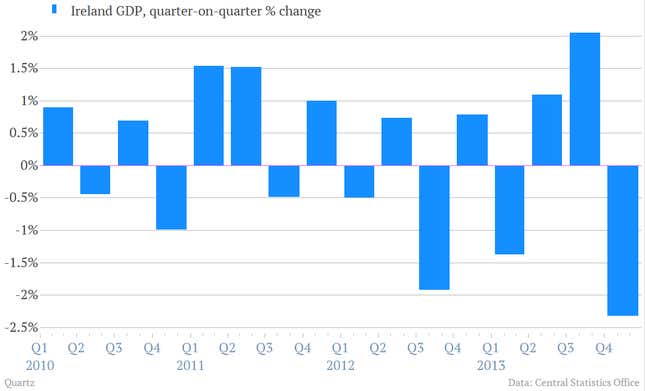

So, today’s ugly reading on Irish economic growth in the fourth-quarter looks a bit surprising. Output tumbled 2.3% during the final three months of 2013, bringing last year’s full-year growth to a measly 0.3%.

But upon deeper inspection, things don’t look so bad. And that has to do with the structure of the Irish economy.

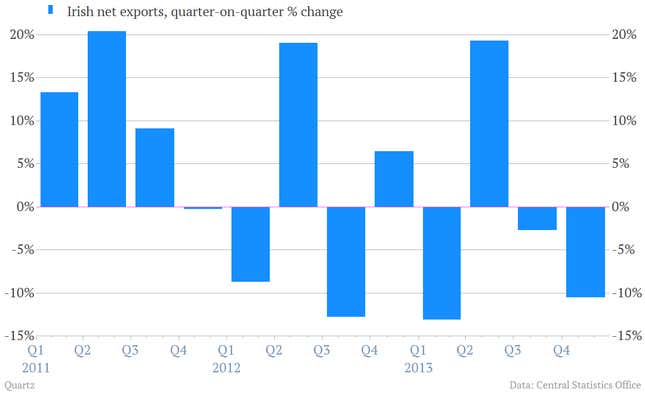

The main reason GDP growth was so weak during the fourth quarter had to do with a sharp tumble in net exports, which fell 10.5% from the previous quarter.

And the key reason for that drop-off had to do with the so-called pharmaceutical “patent cliff,” which refers to the fact that a number of giant blockbuster drugs are set to lose patent protection over the next few years, meaning cheap generics can be manufactured. Ireland is heavily concentrated in pharmaceutical manufacturing. A report published last year by the Irish government noted that nine of the top 10 multinational drug companies were located in Ireland. Pharmaceuticals account for about a quarter of Irish exports.

But the bulk of that money doesn’t recirculate into the Irish economy. It goes into the coffers of large foreign companies. And that’s why economists say that GDP is the wrong metric to use to understand the Irish economy.

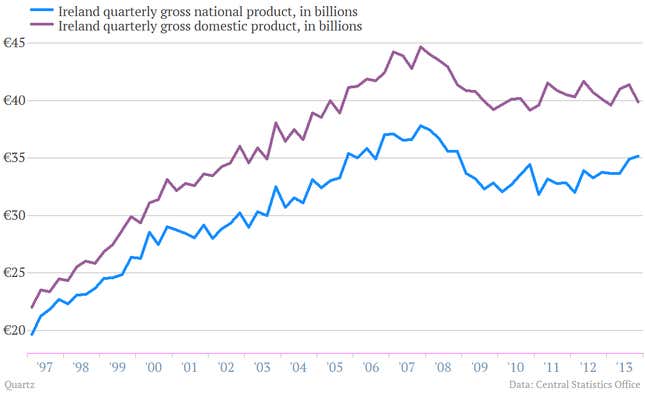

While GDP measures output of all companies operating within Ireland, a separate (but related) measure known as gross national product (GNP) only tracks the output of Irish citizens and companies, wherever that output is produced. In other words, it strips out the impact of foreign multinational corporations and shows how much true income is available to Ireland itself, not just the companies located within its borders.

That’s important because for decades, Ireland has coaxed multinationals to set up shop on the island with tax rates that rival those of known tax havens such as Luxembourg and Bermuda. A recent study pegged Ireland’s effective corporate tax rate at a scant 2.2% in 2011. (The average effective tax rate in the developed world was about 26% in 2013, according to statistics from the OECD.) Those low rates did their job, and multinationals flocked to the Emerald Isle.

As a result, the size of Irish GDP—which includes the output of foreign companies in Ireland—has surged far ahead of GNP in recent years. Here’s a look at quarterly data going back to the late 1990s.

In 2007, the year before the crisis, GDP was about 14% bigger than GNP. When the crisis hit, that gulf grew to almost 20%. But since then, GNP has caught up, and the gap between GDP and GNP narrowed sharply last year, from about 18% in 2012 to 15% in 2013.

In fact, when 2013 was all said and done, Irish GNP was up a tidy 3.4% year-over-year, even as GDP shrank 0.3% compared to the prior year.

In other words, the Irish are doing a bit better than their multinationals, which could explain why they’ve been in such a great mood lately.