As in mainland China, Hong Kongers now use code to evade political censorship

The speed with which Hong Kong has descended into repressive authoritarian rule is being matched by the city’s protesters, who are moving just as quickly to stay one step ahead of censors.

The speed with which Hong Kong has descended into repressive authoritarian rule is being matched by the city’s protesters, who are moving just as quickly to stay one step ahead of censors.

Just two days after the sweeping national security law was signed into force on Tuesday (June 30), the Hong Kong government officially created the city’s first thoughtcrime: it banned the protest slogan “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times,”(光復香港, 時代革命) declaring it to be secessionist and subversive, and hence in breach of the new law.

Legal scholars have already questioned the validity of the government’s blanket ban on the slogan without regard for intent and the scope for different interpretations of the phrase. But whether or not the ban ultimately holds up in court is besides the point. Its mere existence right now fundamentally undermines freedom of speech, expression, and thought.

True to the Hong Kong protest movement’s reputation for being resilient and creatively versatile, people have already come up with all sorts of ideas to skirt the ban on their rallying cry. Where last year Cantonese was creatively deployed as an expression of satire and identity, it’s now used as an antidote to political repression. On the chat app Telegram, protesters have shared different ways to speak in code. Cantonese being a tonal language, there is ample opportunity to swap in similar-sounding characters to create a phrase that sounds like the banned slogan, but means something else entirely.

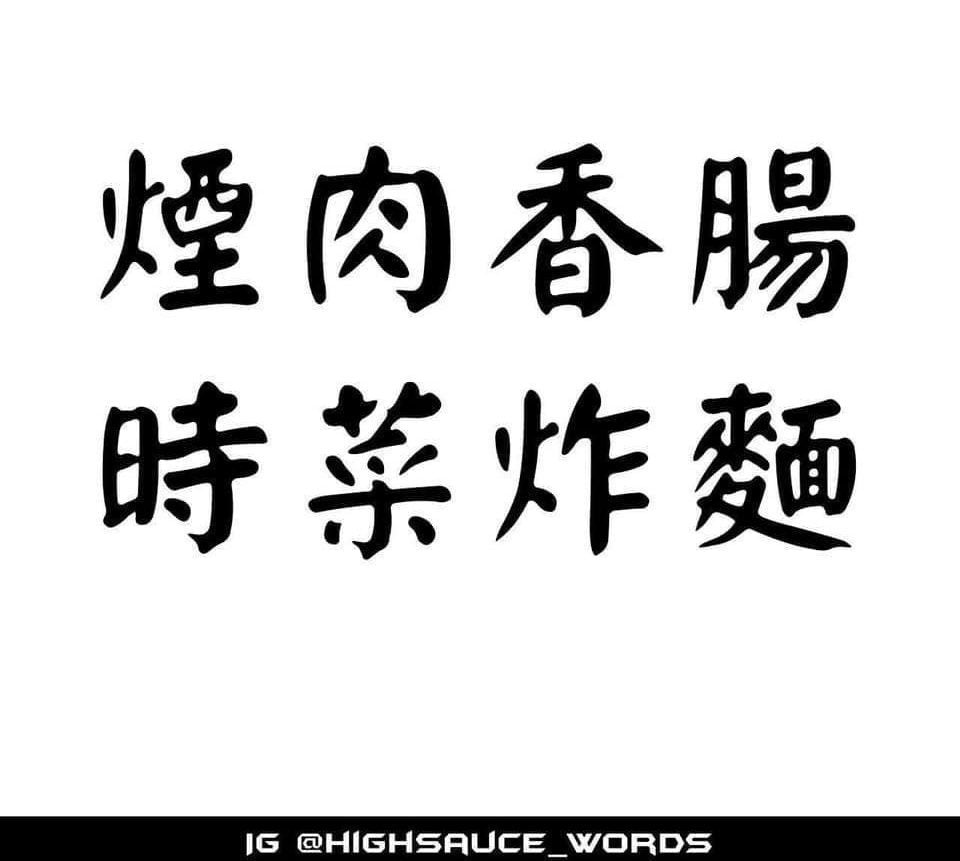

Here’s one example. The eight characters below are near-homonyms for “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times” in Cantonese, which in its original would be pronounced “gwong fuk hoeng gong, si doi gaak ming.” Here, it’s altered slightly to read “bacon and sausage, vegetables and noodles,” pronounced “jin juk hoeng coeng, si coi zaa min.”

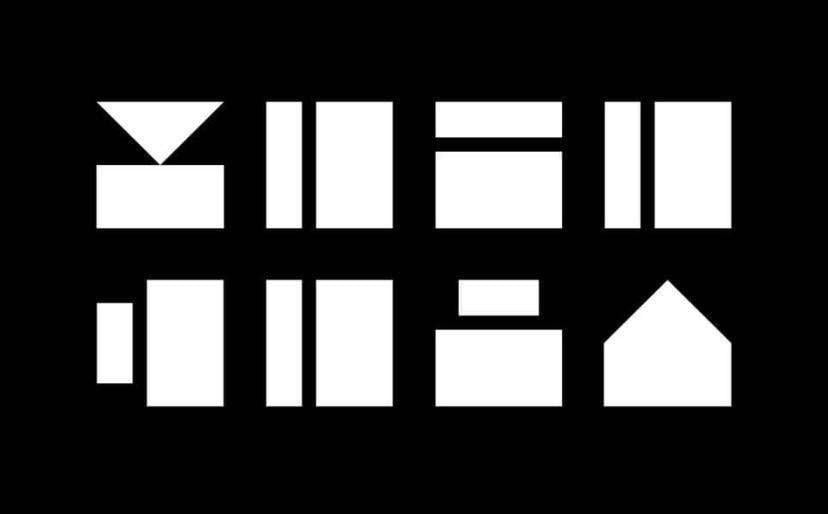

Another example makes use of the pictorial features of Chinese characters to create graphics that look like the characters of the banned slogan, but are actually composed of cartoonish illustrations. Yet another example traces the rough contours of the eight Chinese characters of the slogan, but renders them into mere rectangular and triangular shapes.

“It is clever, but also sad,” wrote Yaqiu Wang, China researcher for advocacy group Human Rights Watch. “Gradually, people adapt to speaking in code. In the end, you don’t know how to talk and think like a normal person anymore.”

Mainland Chinese citizens have long deployed creative tactics to get around state censors. They blur photos to doge image censorship on the chat app WeChat. They use items like rubber ducks and cigarettes to recreate Tiananmen Square’s “Tank Man.” They’ve used “Martian“—a coded language based on Chinese characters that was very popular many years ago—to discuss sensitive topics, including the coronavirus pandemic. And they’ve even used song lyrics as code to show their support for Hong Kong’s protesters.

In another example of defying censorship, after police officers warned a shop that its Lennon Wall—colorful displays of Post-It notes with protest-related messages scribbled on them—was possibly in breach of the national security law, several other businesses put up empty Post-It notes in protest. Others are urging people to put up blank pieces of white paper everywhere to fight what they call the “white terror” that is engulfing the city.

Lian-Hee Wee, a professor at Hong Kong Baptist University who studies Cantonese phonology, is slightly more optimistic in Hong Kong’s case. “We might see Cantonese becoming more expressive,” he said. “And there is a need to express so much now. The need comes about because there is no room for it: it’s precisely because you’re not allowed to speak that you need to speak.”

Wee quoted a Chinese idiom that he roughly translated as, “To put a stop on the mouth of the people is as if you’re trying to stuff up the mouth of the river.” The fact that this saying exists suggests that Chinese people have long grappled with ways to express themselves in spite of censorship. “Talking in code is not new, and Hong Kongers are getting used to the fact that they have to,” he said, whereas during the protests last year and 2014’s Umbrella Movement, “they didn’t have to but they enjoyed doing so.”