This spring, a strangely moving commercial aired across New York State.

It opens with a series of lonely Covid-19 lockdown scenes: an avenue in Manhattan devoid of signs of life, a soulless subdivision, a quiet farm.

Then, as the melancholy music picks up, we see young adults slipping on their jackets and leaving their homes. The voice-over begins: “Do you feel the calling to care for others?” Cut to random people converging on one building where they’re presumably transformed into nurses, hospital aides, and care staff for seniors. “Then you have the caring gene,” the narrator continues, directing viewers to CaringGene.org, a job board site.

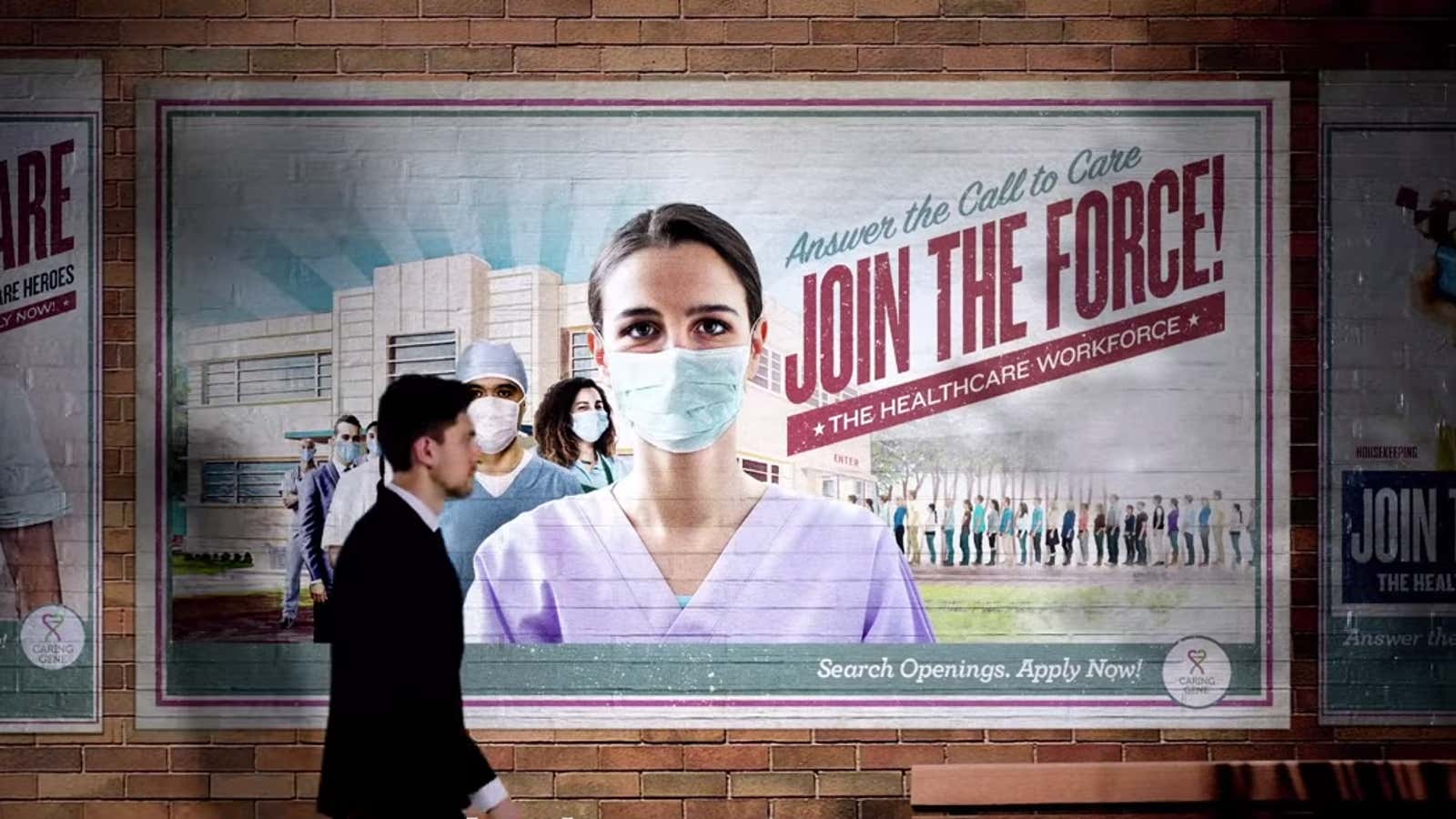

In the parting shot, one masked woman becomes the face of a poster styled like that of a World War II-era US Army recruitment ad. The copy reads: “Answer the call to care! Join the force! The healthcare workforce!”

If that all sounds corny, that’s because it is, or it would be in normal times. Setting up a standard shoot with actors was ruled out because of the lockdown, so the director in this case had to string together stock video clips, according to Amelia Trigg, head of marketing at Iroquois Healthcare Association, the regional hospital association that commissioned the ad. Masks were added in post-production.

Somehow, despite the stock footage, the commercial is effective. Maybe that’s because it’s airing at a time when most of us feel pretty helpless. Or because it stirs a sense of duty in viewers now accustomed to seeing the pandemic as a patriotic battle. It also plays to a person’s ego: Is empathy in your DNA? Whatever it is, the simple spot appears to be working: Daily traffic on caringgene.org—where people can search for job openings and training in senior caregiving and nursing, whether as in-home aids, or for assisted living properties, or in skilled nursing homes—doubled in May and June compared to the period between May to December last year, when the campaign first launched, Trigg explains. Click-throughs to the job search tools and to providers’ websites far exceeded benchmarks or standards, she adds.

The unprecedented high unemployment rate in the US must explain part of the increased interest. Arguably, however, the commercial also captures a changing perception of the senior care industry, now finally seen as part of the healthcare ecosystem. In that sense, it plays to the longtime aspirations of those already in the field.

Changing the image of caregiving

As Quartz reported before the pandemic began, senior caregiving jobs have needed an image overhaul to help boost the occupation’s reputation and value.

Historically, it has been seen as “low-skilled work, sort of naturalized feminized labor,” Kezia Scales, director of policy research at PHI, an advocacy group in the Bronx, said at the time. In skilled nursing homes in the US, the low pay rate prescribed by Medicaid reimbursements adds to the problem, anchoring the salary levels for caregivers in any setting. PHI’s most recent data, from 2018, showed that the average hourly wage for caregivers in senior-living centers and other kinds of residential facilities was $12.07 an hour. Home care aides made an average hourly rate of $11.52, and nursing assistants nursing homes earned a median wage of $13.38 per hour.

Robyn Stone, co-director of the LeadingAge LTSS Center @UMass Boston, a research group, says she has been talking about the need to improve job conditions, including wages and benefits, for years. In her lobbying efforts, she has discovered that people saw the job as akin to babysitting for adults.

The work in fact demands a high degree of competence and emotional intelligence. As the person most intimately involved in the life of an older client or resident, caregivers have to support someone’s physical and emotional health, and their sense of agency. They handle all manner of emergencies or random challenges connected to someone’s diet or sleeping habits, and they juggle the constant concerns and requests of family members. In-home aides manage medications too, which can be a complex task in someone with several health conditions. (Residential providers usually employ a medical technician or “med tech.”) Working with people with dementia requires specific training to understand the disease and how it’s experienced. And of course, frontline caregivers have to know the protocols for infection control. All of this has somehow been downplayed in the wider understanding of the work.

Now, says Stone, the pandemic and its particular threat to seniors in residential settings has also meant that caregivers are being recognized as essential workers and she’s hoping that doesn’t go away. “I think we’re going to be seeing a lot more discussion, trying to figure out better policy solutions for how we support, pay, train, and create career advancement opportunities for this workforce so that we can attract people into the sector, get them to stay in the sector, and to grow in this sector,” she says. “This pandemic really did shed a light on that.”

The senior care industry has been grappling with a shortage of workers for years, in every job category, including in administrative and management roles, says Beth Mace, chief economist of the National Investment Center for Seniors Housing and Care. Studies have suggested that the US will need 2.5 million additional long-term care workers over the next decade and the pandemic has only exacerbated the caregiver shortage problem. Mace expects that the pressure on companies to keep caregivers may mean that the higher wages that were offered as pandemic pay will stick.

If all of these improvements happen, it could be a game-changer for all workers, creating a solid job and a ticket to social mobility in a workforce that has been welcoming to immigrants, particularly women of color. (Roughly 40% of direct caregivers are immigrants.)

But Trigg cautions that her conversations with senior housing providers suggests many facilities will actually be struggling to stay solvent in the near term due to a combination of spending on infection control and fewer move-ins.

In the assisted living sector, operators often say labor is already their highest cost, so paying staff more would be difficult to do without passing that expense on to residents and families.

It’s a conundrum that might require a reset of expectations and greater transparency in the industry. “My sense is that if we’re going to have a quality workforce and a quality frontline workforce with good supervision, which means also good nursing supervision, we’re going to have to take a look at what it really costs more to be there, to do the work,” says Stone. “Something is going to have to give, either the dollars are going to have to shift from pay for other staff to the front line, or margins are going to have to shift,” she adds. “It’s a question for the market.”

The families of those who often make decisions for seniors in facilities could apply some of that pressure to support frontline workers, she adds, if they come to understand the industry better. She’s also hoping that socially conscious millennials and Gen Zers now entering the workforce will take this opportunity “to shape the industry so that it offers more value to society.”

The emotional hook

Before deploying the latest Caring Gene campaign, Iroquois Healthcare was concerned about fear in the marketplace; given the stats about Covid-19 deaths in nursing homes—the vast majority, but not all, among elder residents—they weren’t sure how their pitch would land.

So far, that worry has proven to be unfounded.

In their pre-launch discovery research, the importance of purpose at work was the theme that kept rising to the surface, which bodes well for younger generations’ interest in the work.

Iroquois Healthcare has learned that people believe caregiving is only dead-end, low-paid physical work; in fact, Trigg says, there are always opportunities for promotions, or for further training that might be covered by the employer.

It’s not only physical work either, though it is that, too, says Eileen Murphy, senior director of special projects at Iroquois Healthcare. But, she adds, “people are surprised to find the level of job satisfaction, because of the deep relationships they form with people. They really become like family,” she says, and not only with the seniors, but also their loved ones and families. The connections are unexpectedly deep, she says, adding, “You don’t have that same opportunity if you’re working at McDonald’s.”