A historic economic crash. Geopolitical turmoil dialed up to the max. A pandemic threatening to rip through the world’s population again.

Sound like a good time to buy stocks?

It seems a little nuts, but tens of millions of people around the planet are doing it with zeal. (But not you, right?) In China, regular people are packing into brokerage houses to buy shares. Americans from coast to coast are feverishly refreshing their Robinhood and TD Ameritrade brokerage apps, while newbie traders in India are enamored with penny stocks. A growing number of Brits have taken a fancy to shares.

It’s too soon to call it an outright bubble—a confounding surge in prices before the crash—but research suggests we should be vigilant. A survey of these studies indicates that bubbles are partly caused by standard economic stuff like easy credit and government policy. But they may also spring from the stories we tell each other, as well as the hormone-induced high some people get from trading.

All of those factors are in play today. We live in a time when almost every government is struggling beneath debt loads unseen outside of a wartime, giving politicians ample incentive to inflate a financial balloon to get out of it. Technology is stirring up the kind of wonder that causes investors to think more about getting rich than about boring things like historical earnings. Social media accelerates the spread of nutty ideas, while smartphone apps have put brokerages into hundreds of millions of pockets around the world.

But before we go any further, let’s start in a place where few economists ever go: human biology.

Table of contents

Your brain on trading | Government-made bubbles | Mississippi Company | Bubble technology | Busted | What to do about it

Your brain on trading

“They’re probably getting a real high off of it,” says John Coates, a senior research fellow in neuroscience and finance at the University of Cambridge. That’s “making them more risk-seeking than they were before.”

That’s what Coates said when I asked him about the armchair investors who have jumped into America’s retail trading boom. The former derivatives trader likely knows more than anyone else about the interplay between human biology and trading because he has lived it and studied it. Before he trained in neuroscience and endocrinology at Cambridge, Coates worked on trading desks at Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank in the run-up to the dot-com bubble that popped in 2000.

Two decades after day traders went wild over technology shares, they’re storming the stock market again, helping to push the S&P 500 Index of large US-listed stocks to a record—a rally that is especially incredible considering the economy has about 10 million fewer jobs than it did before the coronavirus pandemic hit. There are several factors contributing to the outbreak in retail fervor:

- Buying and selling securities has never been easier, with slick smartphone brokerage apps just a download away.

- Late last year, a price war between companies like Charles Schwab and Robinhood drove commission charges to zero, as brokerages leaned into other, more controversial ways of making money.

- Interest rates have plunged as central banks like the Federal Reserve do everything they can to keep their economies going. With so little money to be made on bonds, the stock market may seem like the only way to go.

- Some investors likely saw the downturn as a chance to get stocks on the cheap. Some have more money in their pocket thanks to stimulus checks.

And then there’s the steroids.

Coates has called the testosterone hormone the “molecule of irrational exuberance.” He remembers the lead-up to the dot-com bubble as a time when reason and discipline went out the window, when investors were overcome by euphoria and omnipotence. As he writes in his book, The Hour Between Dog and Wolf: Risk Taking, Gut Feelings, and the Biology of Boom and Bust, traders began to walk differently, talk differently, and think differently (a lot about sex).

On Wall Street, he saw traders making ever-more extreme bets, even though the rewards were getting smaller and less likely. Coates felt immune to the tech mania because he had been there before, swept up earlier in his career by bull runs in the bond and currency markets. He had first-hand experience of the feelings of omnipotence and cockiness. “Frankly, I cringe when I think about it,” he writes.

Coates thinks male traders (women have about 10% to 20% of the testosterone that men have) on a winning streak are smacked with a powerful, naturally occurring, narcotic high. Testosterone has physical effects throughout the brain and body when it’s released into the bloodstream. It increases the blood’s capacity for carrying oxygen and can increase muscle mass, and primes the body and mind for battle. The steroid can increase confidence and fearlessness.

Researchers, Coates writes, have found a feedback loop in athletes, in which the winner of a competition emerges with elevated testosterone, setting the athlete up to compete even more aggressively and confidently in the next round. But at some point, the feedback loop backfires. Confidence becomes cockiness. Risk taking creeps into recklessness. As the testosterone cycle feeds on itself, the feeling and emotions it produces can become a person’s undoing.

Coates studied hormones and trading in the field by testing the testosterone levels of 17 young male traders at a hedge fund in London. The men were swinging trades lasting seconds or minutes and amounting to $1 billion or more. The tests found what Coates expected: traders who had higher profits also had higher testosterone levels. The hormone probably gave them an edge by improving their “search persistence,” appetite for risk, and upping their fearlessness in the face of new information.

But Coates worries that testosterone can cause harm if it stays elevated, by making traders impulsive and spurring them to take too much risk. Likewise, the trauma of failure, of suddenly losing a fortune, can cause the body to produce the stress hormone cortisol. If this chemical stays in the bloodstream for too long, a person may become fearful and irrationally pessimistic. It’s pretty much the definition of traders’ attitudes during a bear market crash. Every trader I’ve talked about this with says they know exactly what Coates is talking about.

The testosterone-fueled highs and cortisol-inspired lows could well be amplifying market swings, making booms and busts more exaggerated and economically painful than they rationally should be. Hormones “may build up in the bodies of traders investors during bull and bear markets to such an extent that they shift risk preferences,” Coates wrote. “Under the influence of pathologically elevated hormones, the trading community at the peak of a bubble in the pit of a crash may effectively become a clinical population.”

These days, Coates is researching wearable technology to uncover the gut instincts that have often been ignored, but may be useful to a trader. He says his work and experience underscore the importance of diversity on a trading floor. Women and older men have less testosterone and may be less prone to steroid-induced highs. “If everybody has the same opinion then you get bubbles and crashes,” he said. “You need sellers for every buyer to calm things down, and you kind of get that when you have young and old men and women.”

Government-made bubbles

Coates thinks testosterone can amplify bubbles. Others think government policy is usually the culprit.

Take China, for example. As ground zero for the coronavirus pandemic, its economy shrank in the first quarter for the first time since 1989. Oh, and the old world order that bound China’s economy to the West is rapidly decoupling.

But for China’s armchair traders, what matters is that the government has said, essentially, GO FOR IT: “The clicking of the bull’s hooves is a beautiful sound for our post-virus era,” a front-page editorial said (in Chinese) in July in the China Securities Journal, a state-run newspaper. Shanghai Securities, another government-run publication, was more direct: “Hahahahaha! It looks more and more like a bull market!”

It’s working. After state media gave China’s army of retail stock traders the all clear, a benchmark of shares listed in Shenzhen and Shanghai took off like a bullet. The China CSI 300 index is now trading at levels last seen in five years ago—when China’s last stock market bubble deflated.

The propaganda sends a signal to everyday investors that the Communist Party has their back. The government has the power to expand and contract credit as needed, and to do the same with investor access to the market. In the past, officials have ordered in the so-called national team—state-owned enterprises like insurance companies—to buy-up stocks to keep the market from falling. The government can seemingly inflate or deflate stock prices at will.

Kickstarting a boom is fairly straightforward for the Party, which engineered stock market bubbles that popped in 2008 and 2015, according to William Quinn and John Turner, authors of Boom and Bust: A Global History of Financial Bubbles. Unlike stock markets in the US and Europe, where institutional mammoths like pensions and hedge funds are the biggest players, China’s is mostly made up of regular people. Retail investors tend to be less discerning and rigorous in their analysis than the pros, and that can make the market an especially heady rollercoaster.

At the same time, ordinary Chinese people have few choices when they come to investments. Capital controls make it difficult to buy and sell securities abroad, and returns on bank deposits are paltry. The Chinese stock market can be just about their only choice when they need a place to park a chunk of money. Since there’s little in the way of a social safety net, individual savings are vital for providing for family and retirement.

The country’s previous booms each sucked in tens of millions of people, said Turner, a professor Queen’s University Belfast, in a phone interview. Many of them were grandmothers who would pack their lunches to spend the day at a nearby brokerage. Stock picks might consist of lucky numbers or feng shui principles. “It never ends well,” Turner said.

China inflated its first stock market bubble in 2005, when the government sought to keep newly privatized companies, whose stocks had collapsed around 50% between that year and 2001, from continuing to flounder in the stock market. Officials did so by putting in place lock-ups on some shares and limiting certain types of selling. Spurred on by state propaganda, investors, many of them newbies, flooded the market.

The government orchestrated another boom in 2013. It needed one because the economy was mired in debt after the financial crisis, when the government used easy credit and shadow banking to juice commerce, spending, and jobs. So president Xi made stock market trading cheaper and pushed companies to list shares, according to Quinn and Turner. The stock market rally gave Chinese companies a way to raise equity capital that they could use to pay off debts. In every instance—2005, 2013, and 2020—officials turned to state-owned media to pump out stories to encourage a trading frenzy.

There are a couple of reasons why Chinese officials would want a stock market boom right now. One is the wealth effect—consumers are more likely to spend freely if they see their savings and investments climbing in value. This type of stimulus could help the country’s economy get through the pandemic malaise. Soaring stock prices are also helpful at a time when the US is taking regular shots at Chinese companies, threatening to ban them from stock exchange exchanges in New York. It sends a signal that Chinese executives can look to a vibrant stock market back home.

Mississippi Company bubble

China is far from the only government that has deliberately constructed a market boom. Officials, from monarchs to elected politicians, have been doing it for hundreds of years. For Quinn and Turner, government policy and changes in technology are the two main factors that set off bubbles.

One example is Europe’s War of Spanish Succession, which began in 1701 and lasted more than a decade. It was extremely expensive, leaving world powers stuck deep in debt. France’s ratio of government borrowing to gross domestic product was among the most worrisome—somewhere around 83% or much more (it’s close to 100% now). The usual tricks for reducing liabilities, according to Quinn and Turner, like debasing the currency and writing off a portion of the borrowing, weren’t getting the job done.

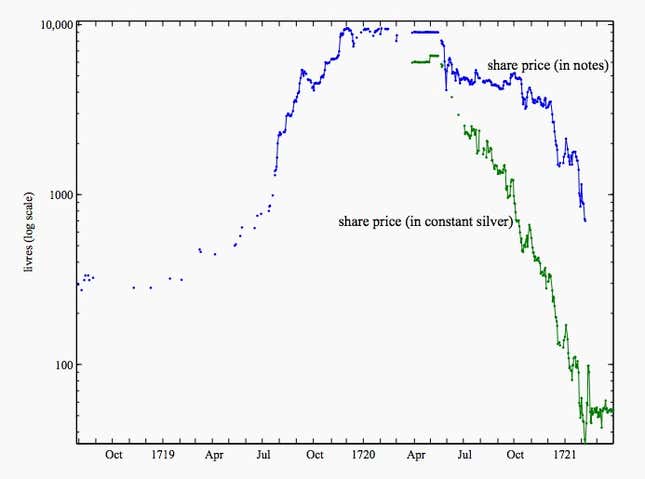

France needed financial innovation. It got it from John Law, a Scotsman, a keen gambler, and a brilliant financial theorist. France allowed Law to charter the Mississippi Company. This enterprise was a massive conglomerate, which France granted trading privileges in France’s North American colonies (from beaver skins to precious metals) and elsewhere; Law was also the architect of France’s own proto-central bank, which provided an innovation—paper money that pumped up the money supply.

The Mississippi Company engineered a way for France to lower borrowing costs by swapping government bonds for shares in the company. To make the whole thing work—to convince people to swap French government debt for shares in the Mississippi Company—Law had to make sure the stock price would increase. He did this by ramping up the money supply, by making the shares easy to trade, and by supplying lots of credit to buy the shares.

It worked so well that it set off a speculative frenzy. Parisian servants who bought shares became, on paper at least, wealthier than their masters, according to The Mississippi Bubble: A Memoir of John Law. Prices soared 20-fold, according to some accounts, and the word “millionaire” was coined. Britain was so impressed by the Mississippi Company that, to reduce its own war debts, it created the South Sea Company, creating its own stock bubble.

Eventually, however, Law lost control, according to Jon Moen, a professor of business administration at the University of Mississippi. The money supply expanded so much that inflation went haywire. The company’s stock price couldn’t remain divorced from reality forever, and it crumbled spectacularly, sending Law into exile.

The craze had all three sides of what Quinn and Turner call the “bubble triangle.” There was marketability, meaning it was easy to trade the securities at brokerages that had sprung up in Paris. There was credit to fuel the fire, adding to the money available to speculate. And finally there were the speculators themselves—the people who are sucked in simply because prices are going up.

Bubble technology

Few things capture investors’ attention more than the promise of technology. In the past it’s been everything from railways and bicycles to automobiles and the internet. The companies capturing the public zeitgeist right now are all about tech, like electric cars and video calls, as well as smartphones and e-commerce.

Sometimes innovation gets attention for a good reason—because it generates abnormally high profits. Then, as Quinn and Turner write, news of the higher prices attracts more traders. Valuations can shoot up and stay up because the technology is novel and its effect on the economy is still difficult to nail down. There’s not much information to figure out precisely what the correct valuation should be.

Technology and the companies that harness it have a way of amping up excitement with a great story, of promising a “new era.” Yale economist Robert Shiller, who won a Nobel prize for his work analyzing bubbles, has focused a lot of his research on the narratives that spread virally. As the author of the seminal book Irrational Exuberance told Quartz in 2017: “Big things happen if someone invents the right story and promulgates it.”

Viral stories tend to leave out boring things like how much the company makes now, how much will it make in the future, and what is likely to go wrong. But there are ways to try to get a sober handle on whether stock prices are overvalued or not. One is known as the cyclically adjusted price to earnings (CAPE) ratio. This measure takes a look at stock prices of companies in the S&P 500 Index and compares them to how much they have earned over the past 10 years. By that measure the US market, which is mostly being dragged higher by a few big tech companies, has spent the past few years in overheated territory comparable to that of the bubble during the roaring 1920s.

So what are the stories going around today? If the questions I get from friends and colleagues are any indication, one narrative is that the pandemic is—or was—a buying opportunity. The US stock market roughly tripled in value between 2009 and 2014, and people who were shellshocked by the financial crisis missed out on that rally. As the saying goes, there’s nothing more agonizing than watching your neighbors get rich.

Some may think the Covid-19 pandemic has caused a “new era.” One in which we will desert our cities, take meetings by video, and get all our stuff delivered by Amazon. There’s a germ of truth here. People are using Zoom and buying stuff online like crazy right now. But the truth is that nobody knows what life will be like after the pandemic is over.

In the meantime, do you think Apple, which now has a market capitalization of more than $2 trillion, is going to sell more iPhones than it was going to before the pandemic started? This chart of the company’s stock price relative to its earnings, a measure of whether a stock may be overvalued, suggests investors think Apple has unlocked a new way to boost profits. Or maybe they’re buying the stock simply because the price has been going up.

Busted

Financial crashes often, but don’t always, have terrible consequences. When France’s Mississippi Bubble collapsed, overall prices in Paris plunged, a deflation worse than during the Great Depression in the US, according to Quinn and Turner’s book on booms and busts. Worst of all, it did little to fix France’s debt burden, and left interest rates higher than they might otherwise have been, potentially contributing to the French Revolution and Napoleon’s later defeat.

Bubble collapses have been just as damaging in recent decades. Banking crises since the 1970s have, on average, knocked down a country’s annual GDP by around 15% to 20%, according to a study by economists at Harvard and the Bank of England. And this says nothing of the human hardship. Reports of distraught investors jumping off of buildings after the Great Wall Street Crash of 1929 were probably exaggerated, but people who lost everything did indeed commit suicide. A decade ago, millions lost their homes to foreclosure after the housing bubble. People who had trained for industries that seemed high in demand, like construction and architecture, discovered their new skills were less wanted in the post-bubble economy.

Some bubbles are probably more benign. Much may depend on whether they infect the banking system, which acts as a kind of transformer, spreading risk from one sector of the economy to another. The South Sea Bubble, for example, may not have been so bad for Britain. The country succeeded in reducing its debts, and those who lost money, Quinn and Turner argue, tended to be wealthy people who could afford to lose it. Britain’s banking system was insulated from the fallout, which helped contain the damage. Likewise, Britain’s Great Railway Mania in the 19th century had some benefits. Investors got crushed, but the country gained train routes that eventually turned out to be viable. The railways made whole industries more productive and kept people employed.

Most of the time, governments aren’t so lucky. Bubbles tend to spread resources around in the economy wastefully. The aftermath can leave a generation of potential investors cynical about financial markets. That means they’re less likely become wealthier by investing, and it deprives viable companies of a source of money to grow.

What to do about it

Bubbles appear to form from an unpredictable brew of factors, from hormones and herd behavior to easy credit and questionable government policy. Fortunately, some ideas about how to tame the booms and busts have emerged.

Coates, who has the benefit of neuroscience expertise and first-hand experience as a trader, thinks diversity could help banks and hedge funds avoid getting carried away. If testosterone can exacerbate a red-hot bull run, having women on the trading desk could help inject a different perspective. Keeping older traders around could help for the same reason: Testosterone peaks in men at age 18 or 19 and gradually dwindles for the rest of his life. (Plus, older traders have the benefit of having survived previous bubbles.)

Bubbles are much more likely to form when interest rates are low, Quinn and Turner write. When rates decline, less-risky assets like bonds have little to offer investors, which pushes investors to take more and more risk. (To be fair, this is exactly what central bankers are trying to accomplish during a recession.) Lower interest rates can also mean it’s easier to borrow money to speculate with.

Relying on ever-lower interest rates to get out of our problems is clearly not a panacea. When unemployment remains high despite low rates, we need to come up with new tools for helping society instead of just finding new ways to lower bond yields. In a telephone interview, Coates suggested that a little more uncertainty about future interest rates could help keep traders from getting too cocky.

Governments have a long history of causing bubbles, and they’re not likely to stop themselves in the future. But perhaps we can mitigate the damage. Because banking crises tend to be especially harmful, we should be suspicious of anything that makes the banking sector riskier. Quinn and Turner’s research, meanwhile, shows there’s such a thing as making speculation too easy. Being able to access a full-service brokerage with a few taps on a smartphone sounds great, but wiring in a little more contemplation might be healthier.

Seen this way, the history of financial bubbles might be more relevant now than ever. US Treasury yields fell to a 150-year low this year, signaling that the risks of easy credit are present and growing. The pandemic has resulted in eye-popping levels of government debt, which will spur officials to look for an easy way out. The spread of Covid-19, if anything, has increased the tech company hype. The barriers to trading are lower than ever, with apps putting a brokerage in every person’s pocket.

This all suggests that we should learn from centuries of booms and busts, and hit the brakes before it’s too late.