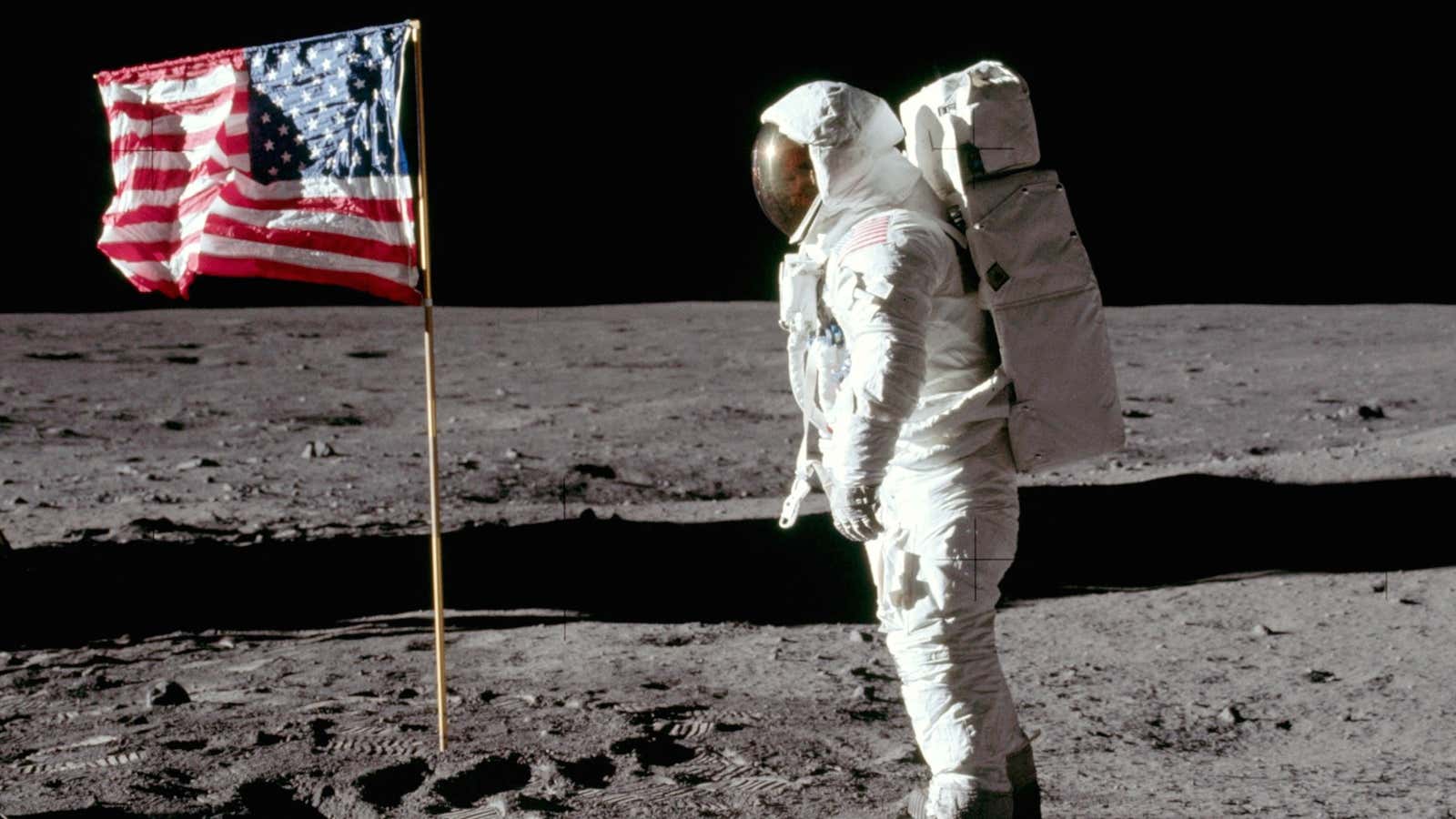

When Robert Hallett was a kid, he wanted to be an astronaut. Everybody did. It was the 1960s, the era of NASA’s exhilarating space shuttle program, and schoolchildren gathered in cafeterias to watch, mesmerized, as miraculous takeoffs and moon landings crackled across tiny black-and-white TVs.

Astronauts seemed to have the most glamorous jobs imaginable: They were superheroes, explorers, scientists. “They were amazing people,” Hallett tells Quartz. “They flew from earth to the moon not knowing what they were going to see.” Who wouldn’t dream of becoming one of them?

Of course, our childhood dreams don’t always crystallize into reality. One recent survey found that only 10% of American adults held their childhood dream jobs. Would-be actors decide to prioritize financial security. Aspiring doctors have the wind taken out of their sails in a tough organic chemistry class. Some lack the confidence to pursue their goals. And some decide, as Hallet did, that a childhood aspiration of flying to the moon just isn’t realistic, and pursue degrees in geology and law instead.

This isn’t necessarily a tragedy. Dreams can change. And if we all stuck with our childhood plans, the world would have an enormous surplus of ballerinas and race-car drivers, and nowhere near enough accountants.

But it’s also true that our biggest regrets in life tend to center around education and career choices, according to a 2005 meta-analysis by Neal Roese and Amy Summerville, published in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

Regrets about the professional road not taken can be particularly painful because they often relate to the things we didn’t do—get a law degree, go to more auditions, try stand-up comedy, study abroad. So-called “regrets of inaction” tend to stick with us because they are “more psychologically ‘open,’ more imaginatively boundless, meaning that there is always more one could have done and further riches one might have enjoyed,” Roese and Summerville explain.

By contrast, we know how “regrets of action” turned out, and it’s therefore easier to rationalize and reframe them as growing experiences—as epitomized in Silicon Valley’s famed “fail fast, fail often” mantra, which champions the importance of making mistakes in order to learn from them.

In a theoretical paper published in The Academy of Management Review, Marijke Verbruggen and her co-author, Ans De Vos, explain why career inaction can have long-term repercussions on our mental health and self-image:

Recognizing that a once hoped for future is not achieved due to one’s own inaction―due to one’s own fault―may feel as a threat to one’s self-esteem and may therefore be particularly difficult and painful…Indeed, the further removed people are from an opportunity on which they did not act, the more convinced they generally become that they would have or could have done just fine if only they had given it a decent try, and when people’s retrospective confidence grows, they tend to find it more difficult to justify their lack of action and, accordingly, they blame themselves even more as time passes.

It makes sense that we have more confidence in ourselves in retrospect: We make a lot of big education and career decisions, with lasting consequences, when we’re young and inexperienced. “As you grow and mature, you’ll gain experience which allows you to ponder and figure out what would have been better decisions that your teenage self could have made, but didn’t,” says Dean Burnett, a neuroscientist and the author of the books The Idiot Brain and The Happy Brain. “Hence, regret is more likely.”

But this doesn’t mean that those of us who feel we’ve made professional mistakes are doomed to keep ruminating about lost opportunities forever. Rather, we can find ways to take control of our own narrative back.

The myth of missed opportunities

One reason why people wind up with career regrets comes down to status quo bias—the fact that people generally have a preference for familiarity and sticking with things the way they are.

“With career decisions, making a change is uncertain and comes with a lot of risks,” says Verbruggen, a professor in the department of work and organization studies at Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in Belgium. “These situations trigger fear and anxiety, and these emotions strengthen the inertia.”

Verbruggen thinks that people often use the idea that they’ve missed a certain window of opportunity as an excuse for their continued inaction. “If there’s an interesting vacancy and you didn’t apply and the deadline has passed, you can still write to the company,” she points out. And while she says that ageism is a real problem, a lot of people never get far enough to find out if their age will work against them. “People say, I’m 50 now, it’s too late … But if you ask, ‘did you try to send out your resume?’ they say no.”

The good news, according to Verbruggen, is that while it’s tough to move from inaction to action, it’s a lot easier to keep inertia at bay once you get some momentum going.

“I think when you start taking action, you might simply continue because it’s the most logical path to take,” she says. “So if you start a new education and you already made the investment, now you’ll search for a new job that’s in line with the degree.”

Of course, it’s not always possible, or practical, to make a big career change. Maybe you don’t have the capital to start your own business, or can’t justify giving up an income for a few years to go back to school. But that doesn’t mean we have to stay mired in regret over inaction.

Here, Hallet’s example is instructive. When he was in his 40s, working as an investment banker and living with his family in Houston, Texas, he learned that NASA was looking to hire a batch of new astronauts. And so he decided to shoot his shot.

Shoot for the moon

Hallet told the story of how he seized the moment on a recent episode of the storytelling podcast The Moth. One day, he and his wife were discussing the NASA openings, and she teased him about the idea that he could make it as an astronaut. “I was a little perturbed by this response,” Hallet said, “So I did what you would expect me to do, I went to work the next day, and I fired up the internet.”

A few hours later, he’d filed the application with NASA, and promptly received an email form letter: Dear Robert, your application for astronaut is now pending with NASA. “I went to my Outlook contacts of 3500-ish people, I pasted every one of them into the BCC line, and I sent this email to everyone with a cover note that said, My application to be an astronaut with NASA is pending, and I’ll let you know if I’ll be around to do your work anytime soon,” Hallet said.

Hallet tells Quartz that his application was somewhat tongue-in-cheek: “They expected something like 10,000 applicants, so you can’t consider yourself having a real chance,” he says. And despite his childhood dreams, it wasn’t as if he’d spent the past few decades mourning the fact that he’d never walk on the moon.

But one night, he arrived home to discover a blinking light on the answering machine. NASA had called. He’d made it through a few rounds of cuts, and he needed to come down for a full physical. Suddenly, his lark was getting serious.

His wife started researching how much money astronauts made (the answer: not enough). His youngest daughter, who was around four or five at the time, said, “Mom, let Daddy follow his dream.”

It was the chance of a lifetime. But the next morning, Hallet called NASA and told them that he was withdrawing his application.

This was partly for practical reasons: He had a family to support, and he wasn’t sure he wanted the space life badly enough. But bowing out also allowed Hallet to rewrite his narrative. He got to follow his childhood dream, at least for a little while, and then end it on his own terms.

“I had enjoyed the dream part of this so much and the fact that it could be possible, that it was great to preserve that as a possibility,” Hallet tells Quartz. He suspected his chances of making the final cut were slim, and he knew, too, that being an astronaut might not have been as amazing as he imagined it would be.

“When you think about careers or major changes in your life, you always romanticize them, but sometimes the day-to-day reality of when those dreams come true isn’t as great,” Hallet tells Quartz. “Every job has its elements that are fun and not so fun. There’s paperwork and bureaucracy; you don’t think about it till you’re in it.”

Repairing the past

The philosopher Søren Aabye Kierkegaard famously captured the inevitability of regret in his book Either/Or, writing: “If you marry, you will regret it; if you do not marry, you will also regret it; if you marry or if you do not marry, you will regret both; whether you marry or you do not marry, you will regret both.” Because we have no way of knowing how our lives would have turned out if we’d made a different choice, there’s no way to guarantee immunity from this particular kind of sadness.

“In a way, regrets about our big decisions in life are deeply tied to the fact that we have just one life to live, and a reminder that it’s not going to be the exact life that we were imagining,” says Shai Davidai, an assistant professor of management at the Columbia Business School who researches the psychology of regret.

But Hallet’s encounter with NASA suggest it’s possible to get some closure with our regrets, even if we can’t exactly fix them.

“Regrets can motivate us to actively search for opportunities to ‘repair’ the past, not just passively wait for those opportunities to arise,” says Davidai. Even if it’s not possible to time-travel back to your 22-year-old self and encourage them to become a veterinarian, you can still volunteer at an animal care center—satisfying the desire to work with furry creatures, and perhaps discovering in the process that you feel faint at the sight of blood, and that it’s for the best that you didn’t become a veterinarian after all.

Another way people struggling with pain over career regrets can take action is to engage in what Davidai calls “mental repair work”—that is, by identifying silver linings (“If I hadn’t stayed at that job, I wouldn’t have met my partner”) and trying to justify why they made the choice they did at the time.

Since regret is a natural consequence of being mortal, a crucial step to coping with it—in our careers and elsewhere—is to remember that it isn’t something to be avoided or repressed.

Part of what makes regret so painful is that the modern-day “no regrets” ideology suggests that successful people always stay laser-focused on the future, and that people who spend time mulling over the past are weak sad sacks, as New Yorker writer Kathryn Schulz points out in a 2011 TED Talk. But regret, as Davidai points out, is simply a sign that our brains are doing what they’re supposed to do: Reviewing our experiences, and trying to figure out what to learn from them.

“If we have goals and dreams, and we want to do our best, and if we love people and we don’t want to hurt them or lose them, we should feel pain when things go wrong,” Schulz says. “The point isn’t to live without any regrets. The point is to not hate ourselves for having them.”