The past, present, and future of the fight to control Hong Kong

Hong Kong marks this year’s Oct. 1—China’s national day—more tightly under Beijing’s rule than ever before in recent memory. Where last year’s Oct. 1 saw citywide protests in a fierce repudiation of China, any attempt at such defiance this year could land protesters in jail for years under the city’s sweeping new national security law. Last year’s forceful resistance has given way to a full-throttle crackdown on dissent as Beijing moves to directly control the city.

Hong Kong marks this year’s Oct. 1—China’s national day—more tightly under Beijing’s rule than ever before in recent memory. Where last year’s Oct. 1 saw citywide protests in a fierce repudiation of China, any attempt at such defiance this year could land protesters in jail for years under the city’s sweeping new national security law. Last year’s forceful resistance has given way to a full-throttle crackdown on dissent as Beijing moves to directly control the city.

But Hong Kong has always defied simple explanations, and the question of whom exactly it belongs to, is no exception. Over the centuries, the city’s degree of control over its own destiny has been in flux—and a sense that the city remains a colony even today has created opposition to China that erupted in mass protests in 2014 and again last year.

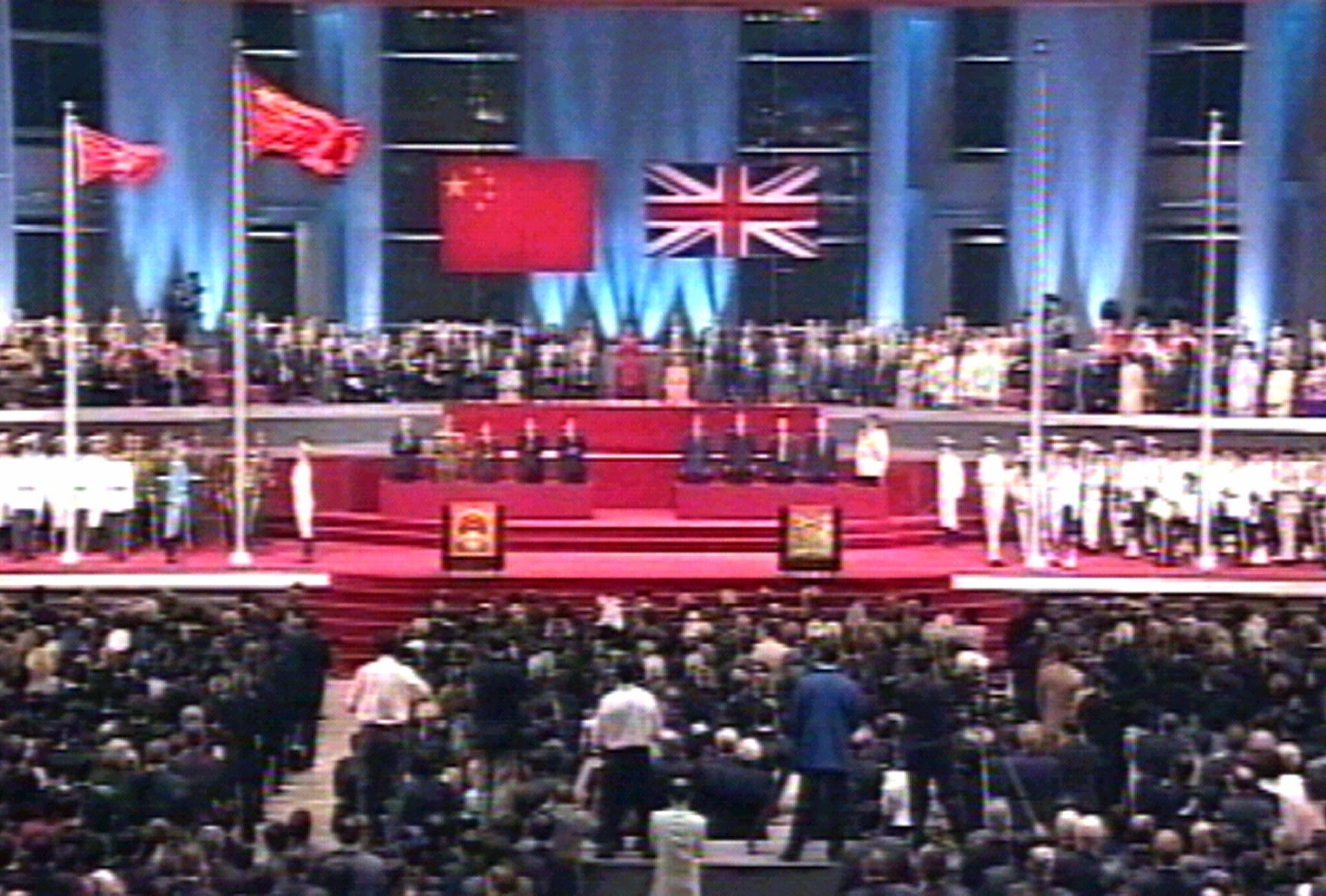

Hong Kong was a British colony for over 150 years and served as an important trading hub, before gradually evolving as a manufacturing hub and eventually turning into an international financial center. Though Hong Kong was handed back to Chinese sovereignty in 1997, the city continued to be a nexus of global connections. Now, as China exerts more direct control over the city, the fight for Hong Kong has gone global.

The present: Hong Kong vs. China

Hong Kong has carved out a curious existence. The semi-autonomous city has, to a certain degree, a say over its own affairs, even if the central government in Beijing ultimately has the final word. Broadly, this arrangement is dubbed “one country, two systems,” where Hong Kong citizens are supposed to enjoy freedoms that their mainland peers don’t have.

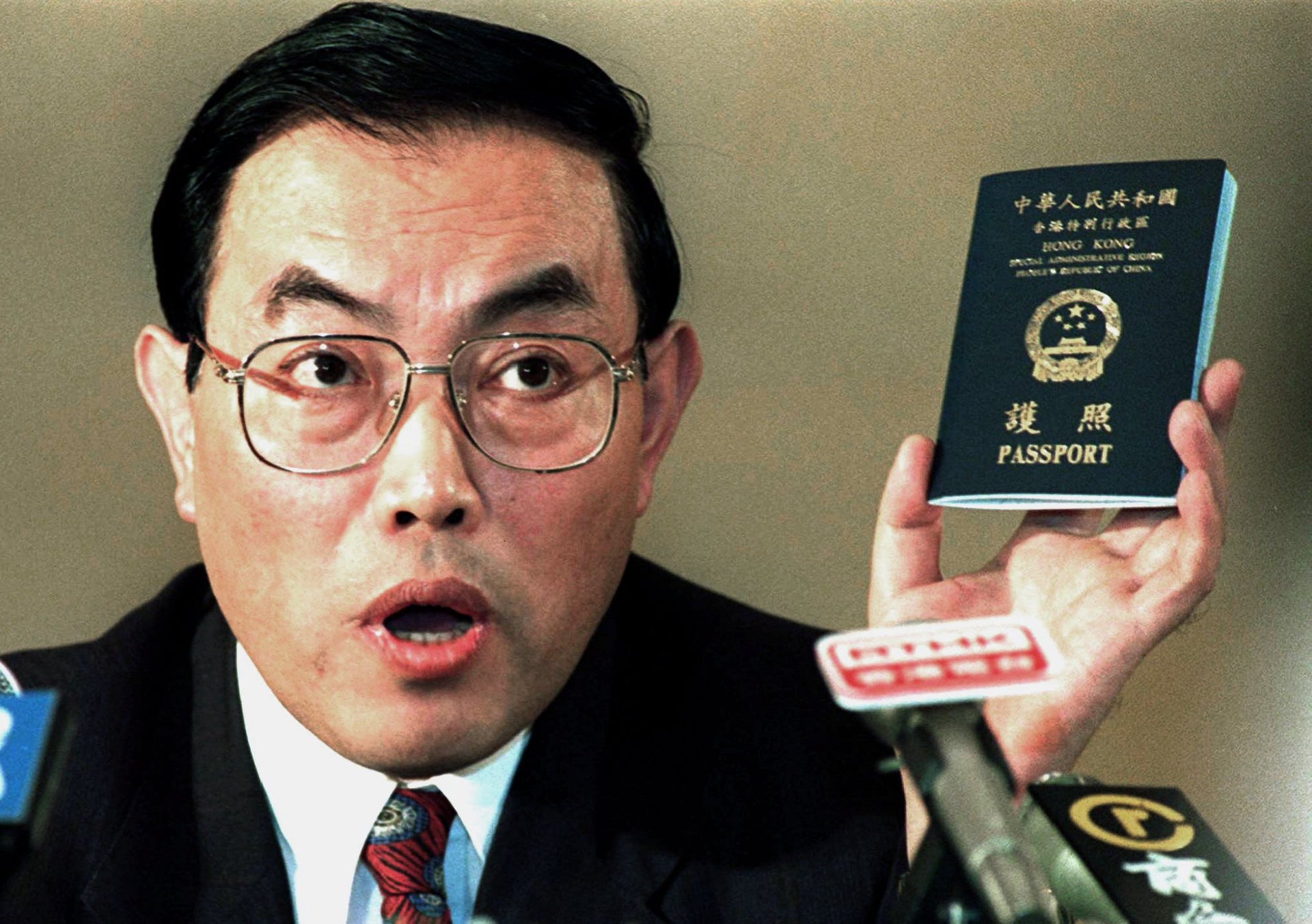

Though it is part of China, it has its own flag, passport (which is “stronger” than China’s), border, airline, currency, and legal and judicial systems. Hong Kongers who want to travel to mainland China don’t technically need a visa, but they must apply for a special travel document. That’s colloquially referred as a “home return permit,” even though people might be using it to visit the mainland for the first time.

Hong Kongers have worried since 1997 about losing their distinct character and legal system built on British common law that made it a haven for people fleeing political upheaval in the mainland. Those fears were realized in 2020 when Beijing circumvented the city’s legal procedures to impose a national security law on Hong Kong, rendering the “two systems” part of the arrangement a hollow shell of a principle.

Under the new law, street protest is all but impossible, internet providers can be ordered by the police to take down content, and journalists face arbitrary visa rejections. Yet, the extraterritorial nature of the law means people all over the world feel more invested in Hong Kong’s fate as the city becomes more like China—while its young people feel less Chinese than ever.

The past: Hong Kong under Britain

Hong Kong became a British colony in 1841, after China lost the First Opium War. More territory was ceded after China lost a subsequent war. Some decades later, Britain significantly increased the size of Hong Kong when it signed a 99-year lease for land known as the New Territories.

So why did Britain return Hong Kong to China? With the New Territories lease set to expire in 1997, the UK in the early 1980s began negotiating Hong Kong’s return to China. Part of the reason was that though Hong Kong Island and Kowloon were ceded in perpetuity, it would have been untenable to split the colony and only return the New Territories. The whole territory would have to be returned to Beijing.

The 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration set the terms for the handover. Under the agreement, China was obliged to maintain Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy, freedoms, and rights for 50 years after the July 1, 1997 handover.

But while Britain’s sovereignty over Hong Kong may be over, its relationship to its former colony isn’t. Many people still have British National Overseas (BNO) passports, a travel document that offered entry but not citizenship. With the arrival of the security law, many democracy activists, see Britain as a new base for Hong Kong activism, even if a flawed one.

In July, in response to Beijing’s actions, the UK government made the unprecedented announcement of opening a citizenship path for 3 million Hong Kongers who are eligible for BNO passports. “We will live up to our responsibilities to the people of Hong Kong,” said Dominic Raab, the foreign secretary.

The future: Hong Kong as an independent nation?

Independence is not a demand widely shared by the public. However, while independence was very much a fringe idea just several years ago, it has gained some traction as Beijing increasingly tightened its control of the city.

In spite of the limited public support for Hong Kong’s independence from China, Beijing has cast the city’s democracy movement as “separatist” and “secessionist” in order to discredit it, and to bring in the national security law. The law makes the vaguely defined crime of secession punishable by up to life imprisonment.

While not independent, Hong Kong can set its own taxes, enter trade agreements with other states on its own, and is exempt from tariffs and customs controls applied on Chinese goods. The US’s dealings with Hong Kong recognized it as having a special status until July this year—when the Trump administration revoked that recognition in response to Beijing’s crackdown.

The constant: Controlling Hong Kong’s economy

There’s another way to look at who controls Hong Kong, beside sovereignty: the economy. In that arena, Hong Kong is overwhelmingly dominated by big business interests—both colonial-legacy British multinational conglomerates, and local business tycoons who historically worked closely with the British colonial government, reaping huge profits along the way. After 1997, they held on to their economic might by working closely with Beijing instead.

Jardine Matheson, the 188-year-old British conglomerate, is one of the biggest landlords in Hong Kong’s business district. It made fortunes trading tea and opium between Europe and Asia, and later evolved to be an investment house. Many streets and landmarks are still named after the firm in Hong Kong, where the movement to replace colonial-era names has never taken off.

Swire, the other major legacy group with huge imprints in Hong Kong, is the biggest shareholder in the city’s embattled flagship airline Cathay Pacific, and a major landlord of malls. But 2019 marked a particularly challenging time for Swire as it suddenly found itself squeezed between the pro-democracy protests and Beijing’s political demands.

Then there are the local tycoons. Four local property dynasties control firms with assets worth more than the city’s GDP, according to Bloomberg. Many of these businesses are core to daily life. For example, there is effectively a supermarket duopoly (pdf, p.9) between a chain under the property conglomerate founded by Hong Kong’s richest man, Li Ka-shing, and its rival owned by Jardine Matheson. The tycoons also have a tight grip on electricity and gas providers, and bus services.

The businesses have vast political power, too. Thanks to Hong Kong’s opaque electoral system, corporate special interests have an outsized voice in the local legislature, and overwhelmingly vote along government lines. Meanwhile, the city’s leader is “elected” in a complicated procedure by a 1,200-member committee that is heavily stacked with business interests. For these reasons, avoiding these kinds of businesses, and favoring small establishments, has been one of the many strategies adopted by Hong Kong’s protest movement to express resistance to China.