Three years after Steve Jobs said he had “finally cracked” it, Apple’s vision for the future of television isn’t much closer to reality.

Apple’s pursuit of TV has included talks with seemingly every major player in the industry. Sources confirm at least preliminary discussions with Comcast, Verizon, AT&T, Disney, CBS, Time Warner, and Viacom.

But the company is stuck between cable providers, which fear losing control of their subscribers, and content owners, which don’t yet see a viable business in the internet. Sporadic negotiations with both types of firms haven’t produced any deals that would allow Apple to launch the integrated television set and service that Jobs described before his death in 2011.

On the cable side, the Wall Street Journal reported this week that Apple and Comcast “aren’t close to an agreement” (paywall) for an internet TV service. Still, it’s notable that the companies are talking at all. Time Warner Cable had been discussing a similar tie-up with Apple before agreeing to be acquired by Comcast last month. The combined company would control about 33% of the pay TV market and 40% of households with broadband internet service in the United States, making it the most important negotiator.

Years of negotiations

Comcast is only part of the story, though. Discussions between Apple and various cable companies have been going on for years, according to people briefed on the talks. Frustrated by the slow progress, Apple last year began meeting directly with content companies, hoping to strike enough deals for content to let it launch its own pay TV service delivered over the internet. As Quartz previously reported, Apple spoke to Disney’s ESPN, Time Warner’s HBO, and Viacom’s Nickelodeon, among other networks.

That strategy hit a dead end too. Apple couldn’t secure enough programming to launch a viable service, sources say, in part because content companies are largely prohibited from making such deals by their existing contracts with pay-TV providers. Even those networks with more flexibility are reluctant to strike out on their own before new models are proven.

The cable advantage

Apple more recently turned its attention back to cable companies, hoping it could strike deals with enough of them to cover a wide swath of the US. With the mobile industry, this was easy: When Apple launched the iPhone in 2007, it only needed an agreement with one American wireless carrier—Cingular, now AT&T—to break into the entire market. But cable companies are more regional, requiring a patchwork of agreements.

In its latest tack, Apple has focused on cable firms that provide both TV and internet service, which include Comcast, Verizon, and AT&T, because those companies would be better able to ensure the quality of streaming video. Other pay TV operators with ambitions to launch an internet TV service, like DirecTV, would have to deliver the content over competitors’ cable lines.

Cable companies seem to view Apple as a frenemy. Its well-established mastery of consumer electronics could help them stem the loss of cable TV subscribers by providing a more enjoyable experience and offering some of the benefits of television delivered over the internet. Comcast has been encouraged by the response to its new cable boxes, which have a vastly improved, web-based interface; last quarter, the company reported its first gain in TV subscribers in more than six years. But that experience could just as easily encourage Comcast to go it alone, concerned that Apple would usurp control over customers in the long run.

Between 30 Rock and a hard place

Within the TV industry, cable companies are chiefly fearful of turning into “dumb pipes” for internet service while others make money delivering content over their lines. Other pay TV services, from satellite operators to potential new competitors like Sony, fret about being middlemen that don’t own much programming themselves. Content companies would seem to have the upper hand in that scenario, but they worry about alienating the cable companies that generate most of their revenue.

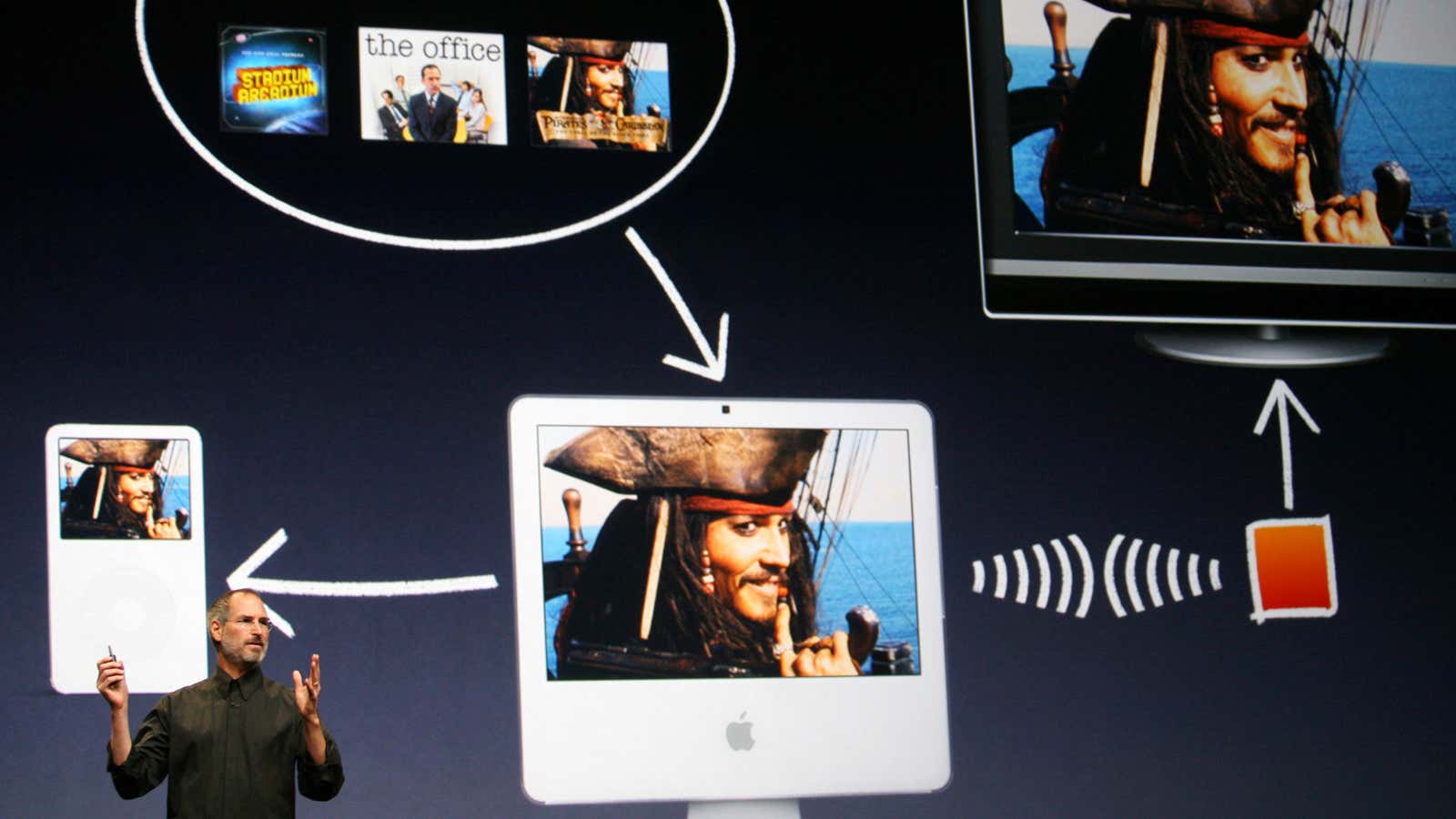

The outlines of Apple’s vision for television are well known. Jobs described it to his biographer Walter Isaacson: “I’d like to create an integrated television set that is completely easy to use. It would be seamlessly synced with all of your devices and with iCloud. It will have the simplest user interface you could imagine.”

The existing Apple TV, a small box that plugs into the backs of television sets, is easy to use but mostly provides access to ancillary services like iTunes, Netflix, and Hulu. Apps for more traditional TV networks, including HBO and Disney Channel, are limited to paying subscribers and don’t provide access to live programming like news and sports.

Balkanization

It’s not clear how much Apple is willing to compromise its initial vision in order to release a television set. It would like to control the experience of navigating channels and provide on-demand access to full seasons of TV shows, but those kinds of features would require agreements with both cable and content companies.

Less revolutionary would be to include a cable company’s app among the options on Apple TV or a future television—similar to existing apps for Time Warner Cable on Roku’s streaming media devices and for Verizon on Microsoft’s Xbox 360. Those are improvements over cable boxes, but far from the Jobsian ideal.

Apple didn’t respond to a request for comment. Other companies named in this story declined to comment or didn’t reply.

The current predicament was predictable. In fact, Jobs explained it well in an interview in 2010:

It’s not a problem of technology, it’s not a problem of vision, it’s a fundamental go-to-market problem.

There isn’t a cable operator that’s national. There’s a bunch of operators. And it’s not like there’s GSM, where you build a phone and it works in all these other countries. No, every single country has different standards. It’s very Tower of Babble-ish. No, that’s not the right word: balkanized.

I’m sure smarter people than us will figure this out.

Four years later, the TV industry is just as balkanized, and no one smarter has emerged to figure it out.