David Ellison has been managing investments for three decades, and these days he focuses on financial company stocks. When I spoke with him last week, there was one IPO on his mind: “I’m hoping to buy some of this Ant Financial, if I can,” said Ellison, a portfolio manager at Hennessy Funds in Boston. “It’s the Amazon of financial services.”

Ellison is far from the only investor hoping to buy a piece of Ant Group, which is poised to raise more than $30 billion in the biggest IPO in history. The Hangzhou, China-based company has evolved into a financial conglomerate that may be valued at more than $300 billion, roughly double that of Goldman Sachs and US fintech darling Square put together. The West doesn’t have anything quite like Ant, and it doesn’t seem likely to create one anytime soon.

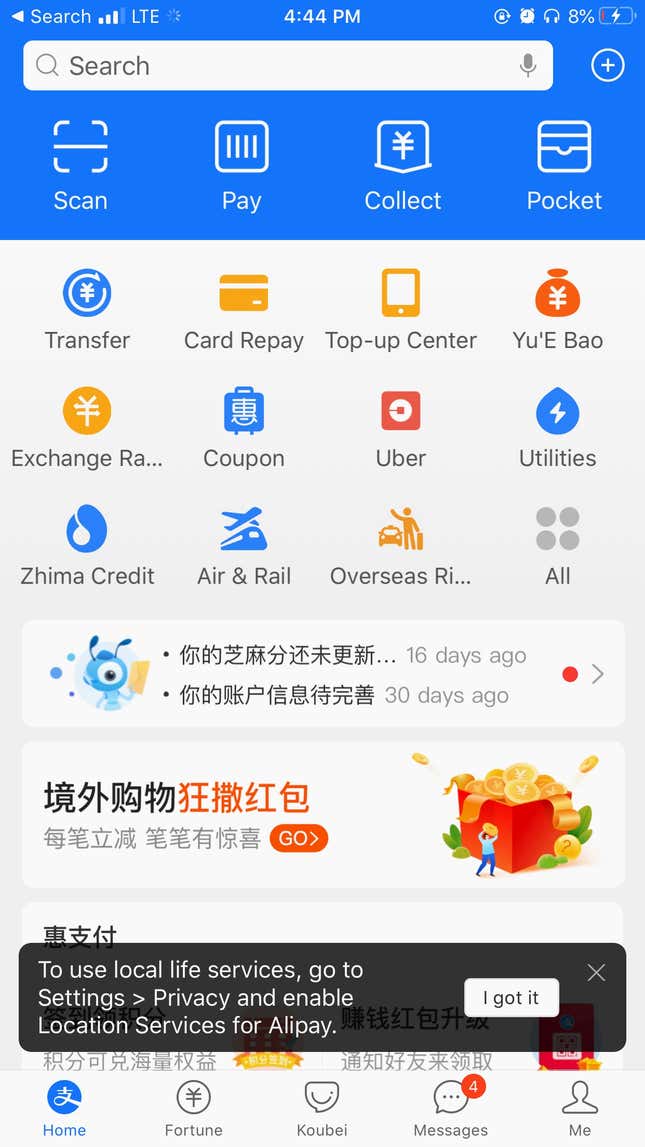

The idea that there could be an Amazon of finance—an internet-native supermarket for money—has been around since at least the late 1990s. Before Elon Musk started making rockets and electric cars, he founded X.com, which merged with PayPal, to do just that. More recently, so-called neobanks in Europe have said they have the same ambition. But Ant, whose valuation is in line to have doubled in around two years, is really the only company that has pulled it off at hyper-scale. The enterprise has brought millions of Chinese people into the financial system, providing a single app, Alipay, for everything from savings accounts to insurance.

Ant has been able to do what startups in the US and Europe haven’t because it started from scratch. By contrast, the West has deeply entrenched incumbents like American banking stalwart JPMorgan, with roots that go back to the 18th century. Credit card giant Visa got its start in the late 1950s. Digital startups talk a great game, but they haven’t disrupted these companies.

When Ant started as the payment arm of Alibaba some 16 years ago, there wasn’t much to disrupt. China’s state-owned banks mainly lent to state-owned businesses, meaning consumers and small businesses didn’t have a lot of great options. Ant has filled that void—it’s what you would get if you rebuilt consumer and small-enterprise finance in the smartphone age.

“Alipay was created in the nascent days of e-commerce to solve the trust issue between buyers and sellers in online transactions,” Ant said in its listing application with Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing (HKEX). “Our mission is to make it easy to do business anywhere.”

The future of Chinese IPOs

Ant shows how far China’s technology and consumer financial sectors have come in the past decade, and its IPO illustrates how far the country’s capital markets have come. The company is planning a dual-listing in Hong Kong and the mainland’s Shanghai STAR market. That’s a major switch from 2014 when Alibaba, the company Ant was spun out of, held its blockbuster IPO on the New York Stock Exchange. (Alibaba founder Jack Ma still controls Ant; Alibaba has a 33% stake in the upstart.)

Relations are obviously frostier between Beijing and Washington than they were then, as the Trump administration has threatened to force Chinese companies to delist from US exchanges, and more recently took a swipe directly at Ant, reportedly considering blacklisting the Chinese fintech. “Listing in China and Hong Kong instead of New York is clearly the preferred way forward for any Chinese company,” said Vey-Sern Ling, a senior analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. Foreign investors are quite comfortable buying Chinese stocks in Hong Kong, as shown by companies like Alibaba and JD.com (originally listed on New York’s Nasdaq) that recently held secondary listings there.

The Hong Kong and mainland markets have evolved since e-commerce giant Alibaba went public. Apart from the STAR market, the stock exchanges on the mainland effectively prohibit listings with higher price-to-earnings ratios, which means startups can end up leaving money on the table during their IPO. Alibaba, for example, would have had to set its offer price lower in 2014 if it had debuted in China instead of New York. But that’s not the case with China’s STAR market, which more closely resembles Nasdaq, and HKEX. On those stock exchanges, companies can debut at higher valuations.

“With all the retail investors in China, it’s quite possible that the market price is going to wind up higher than it would be if instead they had gone public in the US,” said University of Florida finance professor Jay Ritter. “Politically the Chinese government would just as soon have them go public in China or at least in Hong Kong.”

In the meantime, despite the size of Ant’s eye-popping IPO, its valuation appears reasonable, or even cheap, compared with the metrics of other payment companies. According to estimates, the company’s price-to-earnings ratio, a measurement used to discern whether a stock is over- or under-valued, is similar, or lower, to that of other payment companies. Investors may think Ant will have to deal with relatively slim profit margins for some of its financial products.

Back to the future

Ant started out as a trusted way for people to buy things on Alibaba, but it’s far bigger than just a payments platform now. Job seekers can use it to find work, and married couples can get wedding licenses with it. But digital payments are still at its core, pulling in users and generating data that can be used for analyzing creditworthiness in real time and making loans. Last year, Alipay handled more than $17 trillion of transactions, which is more than Visa and Mastercard combined.

These days Ant says it’s the biggest provider of online credit for consumers and small- and medium-size businesses, the largest online investment platform, with around $600 billion in assets under management, and the top online insurance platform in China. It partners with hundreds of banks and money management firms to offer these services to the more than 700 million users who log into their Alipay app every month.

Government crackdown

Diversification is important for Ant, because it needs flexibility in the face of regulatory changes that could threaten its profitability. (Heavy financial regulation, incidentally, is almost certainly a key reason why American tech giants like Apple and Google, now under antitrust scrutiny in Washington, haven’t waded deeper into financial services.)

In recent years, the Chinese government cracked down on the financial upstart, requiring it (and rival Tencent, which operates WeChat Pay) to set aside customer payments as a reserve instead of investing the money for a profit. Likewise, officials tightened restrictions on Yu’e Bao, which had ballooned, almost accidentally, into the world’s biggest money market fund. “Arguably the biggest risk factor to consider for Ant’s future is regulation,” Kevin Kwek, an analyst at Bernstein, wrote in a note to clients. “We think Ant has a track record of managing these risks relatively well and are therefore not overly concerned, but nevertheless recommend incorporating them in valuation assumptions.”

Another key concern is whether the People’s Bank of China will disrupt Ant via its digital yuan. As the country becomes increasingly cashless, Chinese officials are designing their own virtual currency, which is being tested in Shenzhen. A digital yuan could help the government maintain its grip over the payment system and give it more insight, through tracking, into transactions than it has ever had.

Kwek says digital yuan disruption is one of the top questions investor have about Ant. He thinks this digital cash is a notable, but surmountable, risk for the company. “We believe Ant’s ecosystem of products with an already large user base would be difficult to replicate and hence allow Ant to largely defend its market share,” he wrote. The “PBOC is not aiming to disrupt third party payment systems like Ant.”

The future of Ant

Ant has expanded abroad mainly through investments in companies like Paytm, the Indian payments upstart, and UK payment group WorldFirst. But revenue from those stakes remains relatively small, and skepticism about Chinese companies has grown. Ant’s scope to invest or expand in the US and even Europe isn’t straightforward. “Ant should be assessed more on its domestic opportunities than overseas,” Bloomberg’s Ling said. “Their key asset is Alipay, which acts as a gateway for their customers to access their other financial services, and also serves as a cheap way of acquiring new customers.”

“They do not have such an equivalent gateway outside of China, so investments seem like the only way to go,” he added.

That suggests Ant’s future growth will mainly come from China, the world’s second-biggest economy with a rapidly growing and digitally savvy middle class. Even there, Ant executives must always look over their shoulders at Tencent, which has a 47% share of the digital payments market, compared with Ant’s 51%, according to Bernstein data.

“Ant is ahead by a big margin despite starting out in the key areas largely within a year or two of each other,” Kwek wrote. “But the gains have been hard-earned and competitive pressure is unlikely to ease, and remaining dominant in the payment space stays critical.”

—With assistance from Jane Li in Hong Kong.