China loves it. Wall Street fears it. Washington wants it to go away. Meet Ant Financial, the fintech company that’s worth about twice as much as Goldman Sachs.

It’s hard to overstate how big Ant has become since its payment service was started some 15 years ago. It runs the world’s biggest digital wallet and offers the biggest money market fund. And unlike most other Chinese financial companies, Hangzhou-based Ant has ambitions far beyond its home market, having made investments around the world, from the UK to Thailand.

Ant springs from billionaire Jack Ma’s other company—e-commerce giant Alibaba—but the fintech firm has become its own important story. It has gone from a clunky, fax machine-enabled payment service to a futuristic app, known as Alipay, that can handle more than three times as many transactions per second as Visa. Along with a constellation of affiliates, Ant reaches more than 1 billion users around the world.

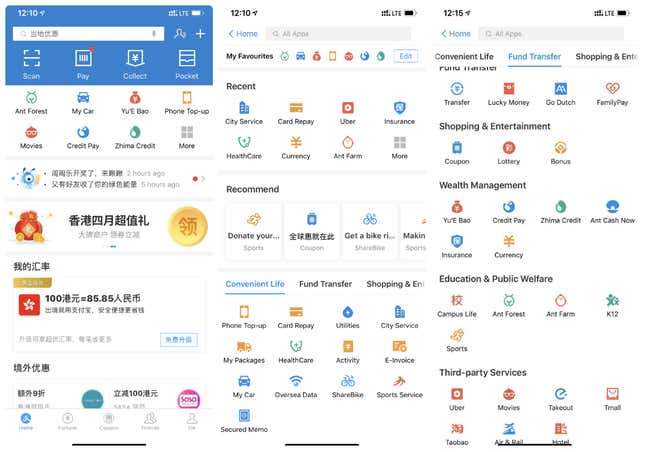

It’s tempting to compare Ant to western companies: is it like PayPal? Square? A combination of both plus Mastercard and Facebook? All of these analogies fall short. “In the wallet itself, we do more than just payments. You have the ability to pay utility bills, you have the ability to apply for a marriage license,” Souheil Badran, the former president of Alipay North America, said last year. “Over the years we’ve combined everything into one wallet, one single sign-on.”

Alipay and its main rival, Tencent’s WeChat, are the twin pillars of China’s mobile payments market, but they are still, in some respects, connected to creaky state-owned banks, which are subject to the whims of the Communist Party. It’s fintech with Chinese characteristics.

Given its success, Ant has become too big to ignore. JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon noted in his annual letter (pdf) this year that he is “both impressed and a little worried about” China’s fintech progress, a sentiment shared by Robert Kapito, co-founder of BlackRock, the world’s biggest money manager.

As Ant’s power grows, so do its challenges. Officials in Beijing have clamped down on the technology firm, crimping its profits. Ant raised almost as much from private investors last year as all US and European fintech startups combined, but it’s burning through cash to fend off arch-rival Tencent. A long talked about IPO appears to be on hold, indefinitely.

The next steps for the financial juggernaut with the diminutive name are likely to the toughest.

Table of contents

Ant’s origin story • The Yahoo affair • How Ant got its name • Four people you should know • What is Alipay, anyway? • Yu’e bao: The world’s biggest money market fund • Timeline • The rival: Tencent • Why has Ant’s IPO been delayed? • Ant’s global ambitions

IN THE BEGINNING

Ant’s origin story

Ant Financial is what you get when you rebuild consumer finance in the age of the internet and smartphones. It started with Alipay, which over time expanded its services to fill a void: China’s state-owned banks mainly lent to state-owned businesses, which meant there were hardly any financial services for regular people and small businesses.

“Initially, when these companies started in China, they started out copying the West—copying Facebook or LinkedIn or whatever,” says Anju Patwardhan, a managing director at CreditEase, a Chinese fintech venture capital fund. “And then it got to a point where they were able to do similar things in China very quickly. Now they’re doing things before the West and the speed things are happening is mind boggling.”

Not that long ago, there was little in the way of credit cards or car loans, and financial regulation was undeveloped. Most foreign competition was blocked by the government. That created an opportunity for China’s fintech upstarts: “They had a massive runway,” says Patwardhan, who is also a visiting scholar at Stanford.

Alipay started out small, in around 2004, as an escrow service. Taobao, Alibaba’s version of eBay, needed a way for buyers to be sure they received their purchases, and for sellers to be sure they got paid. Alipay became the place where buyers would wire money via a post office or bank, with bank slips sent to Taobao by fax machine, according to Duncan Clark’s Alibaba: The House that Jack Ma Built. Alipay workers double-checked all the documents and confirmed transactions, which created a trusted way to transact on the internet in China.

“It started with the evolution of trust,” says Jacqueline Reses, a former Alibaba board member and Capital Lead at San Francisco-based fintech Square. It was a turning point for China’s e-commerce: Until Alipay came along, there was little faith among consumers about buying things online. “The genesis of Alipay was so important as a foundational commerce platform that it became something that is much broader in the minds of Chinese consumers,” Reses says. “Their usage patterns reflect that.”

It was primitive, but Taobao and Alipay managed to outflank eBay and PayPal, which were run by CEO Meg Whitman at the time and were trying to push into the Chinese market. As Clark’s book describes it, PayPal’s failure in China against Alipay came from a combination of mismanagement and regulatory obstacles, as well as a series of rapid upgrades at Jack Ma’s company. Alipay’s technology has evolved from relying on faxes to handling some 256,000 payments per second (Visa says it can handle 65,000).

Over time, China’s mobile payment market grew along an elegant S-curve, carrying Alipay with it. Now, Alipay underpins Tmall and Tabao, two of the largest online marketplaces in China. The payment service, originally designed for desktop, blew past PayPal five years ago to become the world’s largest provider of payments via mobile devices. Even prisoners use it.

Alipay was eventually spun out from Alibaba around 2010 (more on that epic controversy below) and was placed into an entity, with Ma holding the biggest stake, that became Ant Financial. The financial and ownership arrangements are tangled: Alibaba and Ant Financial have a profit-sharing agreement (pdf), which Alibaba said will be replaced with a 33% stake in Ant.

Where Ant goes from here is equally complicated. The staggering size of its world-leading Yu’e Bao money market fund (more on that below, too) has become a risk to China’s financial system. The void in financial regulation helped power Ant’s initial rise, but scrutiny from Beijing will be an ever-present factor in its future.

When Ant and rival Tencent started offering financial services “there was no one to complain—they were allowed to grow and revolutionized the system,” says Patwardhan of CreditEase. “Now it’s too big. They’ve gotten to the point that the government is starting to intervene and clamp down. They’re seen as not too big to fail, but too big to manage.”

Visa’s CEO agrees. Asked in a conference call in January about Chinese competition, Al Kelly told analysts that Alipay and WeChat have their hands full with a “whole bunch of changes,” such as holding more capital for their mobile wallet networks and reducing the yields they can offer through their money market funds. “I still expect them to continue to look to grow outside of China, mostly in Asia,” Kelly said.

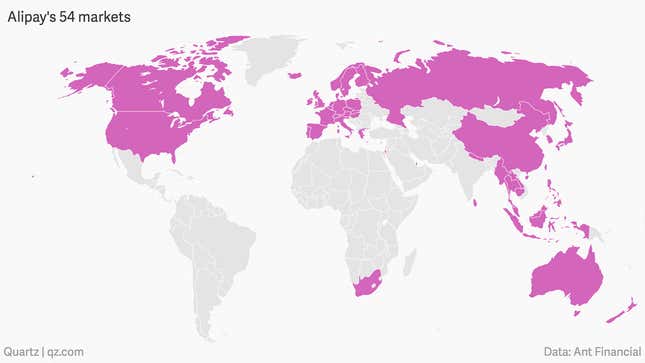

Indeed, Ant wants to double its reach to 2 billion consumers around the world, via investments and partnerships in countries like South Korea, Japan, and India. At the same time, however, it reportedly aims to reduce the share of revenue it gets from payments to under 30%, from around 50% today. Ant is mid-pivot: Reuters reported last June that the fintech firm is shifting away from consumer finance and aims to make 65% of its revenue by providing financial technology to other institutions within five years.

HIGH STAKES

The Yahoo affair

One of the smartest moves that Yahoo ever made was buying a stake in Alibaba. And one of its darkest days was when its ownership of Alipay went missing.

The story goes back to 1997, when Yahoo founder Jerry Yang was one of the most important tech entrepreneurs in the world. During a trip to China, Yang was assigned a tour guide from the economic ministry who, of all people, turned out to be Jack Ma. Around eight years later, after Ma had started Alibaba, they hammered out a deal in 2005 for Yahoo to acquire a 40% stake in the e-commerce company, according to a telling of events in Forbes.

Then, sometime around 2010, Alipay was spun out of Alibaba. As Clark describes it in Alibaba: The House that Jack Ma Built, the payment service was already worth more than $1 billion according to some estimates, but it was transferred into a company which Ma personally controlled at a price of about $51 million. Ma claimed it was vital for the transfer to take place because the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) wouldn’t provide the necessary licensing for a payment company that had foreign ownership.

It was a painful period for Yahoo, since Tencent’s payment service managed to win such licensing despite having foreign ownership. (South Africa’s Naspers bought a 46.5% stake in Tencent in 2001.) It was much sweeter for Ma, who had sold much of Alibaba (and by extension, Ant Financial) to investors: In 2014, he owned less than 8% of Alibaba, while SoftBank held 37% and Yahoo 24%.

The Alipay transaction blew a hole in Yahoo’s share price, wiping billions of dollars from its market capitalization. It was eventually decided that Yahoo would receive as much as $6 billion from a future Alipay IPO. (Yahoo has since been acquired by Verizon and is liquidating its stake in Alibaba.) Based on last year’s $150 billion valuation for Ant Financial, Alibaba’s 33% stake would be worth about $50 billion. Ma still controls the majority voting interest in Ant, according to a US regulatory filing that didn’t disclose the size of his current stake. The Bloomberg Billionaires Index credits him with an 8.8% stake in Ant, down from 48.5% in September 2014.

Does foreign ownership still matter for Ant? IPO rumors have long swirled around the company, which has raised substantial funds from foreign investors like New York-based General Atlantic and Canada’s pension plan, as well as from state-owned banks like China Construction Bank and China Development Bank, according to PitchBook data. A spokesperson for Ant said the PBOC’s rules for ownership and payment licenses were updated in 2018, relaxing restrictions on foreign ownership of payment companies.

After raising $14 billion from investors last year—the most ever for a private company—Ant Financial’s CEO, Eric Jing, said the company doesn’t have a timetable for an IPO. Ant, after all, now has a sizable war chest to see off the threat from Tencent, while also investing around the world. Delaying the IPO could avoid disappointing investors: The company’s $150 billion valuation from its last funding round is so lofty that it could be difficult for investors to cash-in the way they might like. “We never have a timetable for that,” Jing said in a CNBC interview in November.

KING OF THE HILL

How Ant got its name

Ant’s CEO says the company got its name because ants are small and its service was for the “little guys.” And it’s true—there wasn’t much out there for smaller enterprises and regular people in China before companies like Ant came along. Jack Ma has said that Ant’s goal “is to solve the problem of a lack of inclusiveness.”

It makes for a good soundbite. But Ant and Tencent are running cashless campaigns and rapidly driving paper banknotes and metal coins out parts of the economy, much to the alarm of the central bank, which is concerned about farmers and elderly people getting left behind in the nation’s digital overhaul. Although it’s expanding at a phenomenal pace, some estimates put China’s internet penetration at just 58%.

At the same time, only 14% of small Chinese businesses have access to loans or lines of credit, compared with 27% of smaller firms in G20 countries, according to a joint report published by the World Bank and PBOC. Ant has started to make a dent on this market.

Its MYBank brand uses the so-called 3-1-0 model: borrowers complete online loan applications in three minutes, get approval in one second, with zero human touch. MYbank provided more than 1 trillion yuan ($148 billion) of financial support to small and micro enterprises last year, and 96% of those were in loan amounts of less than 1 million yuan. This is, however, a drop in the bucket compared to the $19 trillion or so of loans outstanding in China’s entire banking sector, according to a working paper by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

KEY PLAYERS

Four people you should know

Jack Ma

Age: 54

Role: Founder of Alibaba, credited with 8.8% stake in Ant Financial, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

Background: Ma had a modest upbringing. He was an English teacher, then a translator before he started China Pages, one of China’s first commercial websites. He started Alibaba as a business-to-business site in 1999, a platform that went on to sprout some of the biggest e-commerce venues in the world. He now sits on a pile of wealth amounting to $43.6 billion, making him the 19th-richest man in the world, according to Bloomberg.

Lucy Peng

Age: 45

Role: One of the founders of Alibaba. Formerly a top executive at Alipay and Ant Financial.

Background: Peng taught at a university in eastern Zhejiang province before becoming one of the 18 co-founders of Alibaba. She had been chief people officer with the company for more than 10 years before being appointed Alipay’s CEO in 2010, and later added executive chairwoman to her titles. Peng became CEO of Lazada, an Alibaba-backed e-commerce business in Southeast Asia, in early 2018. She stepped down later that year, amid signs it was losing ground against Shopee, part of Tencent-backed Sea. She’s still Lazada’s executive chairwoman. Peng has a net worth of $1.1 billion as of 2018, according to Forbes.

Eric Jing

Age: 46

Role: Ant Financial’s CEO.

Background: Educated in prestigious universities in China and the US, Jing spent his early career at beverage company PepsiCo Guangzhou as chief financial officer from 2004 to 2006, before joining Alibaba in 2007. He started working at Alipay two years later and served as chief operating officer, president, and chief financial officer. He succeeded Peng as Ant’s CEO in 2016 and became executive chairman in 2018.

Pony Ma

Age: 47

Role: Founder of Tencent.

Background: A computer science graduate from China’s southern Shenzhen University, Ma founded Tencent with an early focus on instant messaging in 1998. Tencent’s flagship products include QQ and WeChat. Tencent went public in Hong Kong in 2004. Ma is one of the richest men in China, with a net worth of about $40 billion, according to Bloomberg.

SHOW AND TELL

What is Alipay, anyway?

- Alipay: mobile payment and lifestyle platform

- Huabei (Ant Credit Pay): a type of virtual credit card that facilitates credit payments; users can buy items with credit and repay via installments

- MYbank: a private online bank based on the cloud, directed at small and micro enterprises

- Jiebei (Ant Cash Now): a consumer loan service

- Ant Fortune: a comprehensive wealth management app, which includes Yu’e Bao, the world’s largest money market fund

- Zhima Credit: an independent, private, alternative credit assessment service

TREASURE TROVE

Yu’e bao: the world’s biggest money market fund

You know you’ve made it when you become systemically important to China’s $14.2 trillion economy. Ant Financial’s Yu’e Bao was launched in 2013 and became the world’s largest money market fund within a few years. Some 588 million (paywall) Alipay users—more than one-third of China—access the fund. Tianhong Yu’e Bao was launched by Tianhong Asset Management, which is 51% owned by Ant.

The fund, whose name means “leftover treasure,” was originally designed to give customers a way to save small amounts of money sitting in their Alipay accounts. Chinese consumers are rich in savings but poor in opportunities to invest. Now, the fund oversees the equivalent of about $170 billion in assets, as of December.

Yu’e Bao is popular because it’s easy to use. Chinese consumers treat it like a checking account, and are able to pay for anything from taxis to coffee straight from their investment holdings. It isn’t the highest-yielding money market fund in China, according to Li Huang, associate director at Fitch Ratings in Shanghai. Instead, Yu’e Bao’s extraordinary popularity comes, in part, from how seamlessly it is integrated with Alipay.

Many users may not realize that Yu’e Bao is riskier than a savings account. But the Chinese government does, which is why watchdogs have begun cracking down. As a result, the fund invests in more liquid assets, and Alipay’s fund platform now offers around 19 other money market funds that aren’t run by Ant Financial and Tianhong Asset Management.

Assets overseen by the Yu’e Bao fund itself have declined by a third or more from their peak a year ago. But it’s still bigger than other giant funds, like JPMorgan’s $136 billion US Government Money fund.

It faces two key questions: Will it still be the largest fund of its kind in a few years, now that government regulators have cracked down, reducing its yields? And what does it say about the Chinese economy that so much money is sitting in a money market fund instead of going to more productive uses? As innovative as the Alipay platform may be, its Yu’e Bao fund invests in deposits that end up with regular banks.

MILESTONES

Timeline

Ant Financial has come a long way in the past 15 years, from a primitive escrow service for online shopping to a sprawling, app-based global payments conglomerate. Here are some of the highlights so far:

THE OTHER SIDE

The rival: Tencent

As powerful as Ant has become, it still faces stiff competition at home. Tencent’s WeChat started out in 2011 as “Weixin,” also known as China’s answer to WhatsApp. Over the years it has morphed and mutated into something the internet has never seen: An all-in-one super app that lets users hail drivers, find dates, or order food. WeChat Pay, which was rolled out in 2013, has since made cash and credit cards obsolete for many of its users.

It got there by embracing QR-code technology that smartphone cameras can scan and use to exchange anything, from contact details to money. The app has digitized parts of China’s culture: more than 760 million people exchanged digital versions of red envelopes containing cash during last year’s Spring Festival, as the number of digital hongbao exchanged increased about 10%.

Alipay is bigger in terms of payment volume, but data from late last year shows that Tencent has deeper penetration among the Chinese public, at 84% versus Alipay’s 64%.

In recent quarters, Alibaba executives have acknowledged that it is burning cash as it competes for new Ant users. “We have done a lot, together with Ant Financial, Alipay, to acquire new customers,” Alibaba CEO Daniel Zhang said Jan. 30 in an earnings call.

WAITING LIST

Why has Ant’s IPO been delayed?

Investors and investment bankers have been on the lookout for an Ant Financial IPO for years, but it has yet to materialize. Here are three likely reasons for the delay, according to Vey-Sern Ling, a senior analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence:

- Plenty of money already: The company raised $14 billion last year, the most ever for a private company. Why rush to list? Ant executives have been able to raise capital seemingly at will, without the hassle of going through an IPO.

- Wobbly financials: The company’s recent focus on defending its market share against WeChat Pay has dragged its profits down. “It probably doesn’t look that great for an IPO,” Ling says. (Not that this has stopped other companies of late.)

- Business model revamp: China’s regulators have clamped down on fintech businesses that previously had little oversight. The crackdown has crimped profits, and Ant is seeking to focus on its tech credentials rather than its financial ones. Going public mid-pivot might not be the best idea.

NEXT STEPS

Ant’s global ambitions

In case there is any doubt about how some US officials feel about Ant Financial, consider this email from former congressman Robert Pittenger, one of the lawmakers who successfully sought to block Ant’s acquisition of MoneyGram: ”The threat remains real from Ant, we must always recognize that Ant is controlled by Beijing,” Pittenger wrote to Quartz in March. “Ant Financial payment technologies and further acquisitions warrant ongoing review by our intelligence community, to be shared with our global partners, especially with the Five Eyes.” (Five Eyes refers to the government intelligence sharing network made up of the US, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.)

Ant disputes this characterization and says that it is neither owned nor controlled by the Chinese government. “Similar to external shareholders of any company, investment funds never have access to private customer data,” a spokesperson said. “Requests for data from any government are reviewed and complied with in accordance with applicable laws.”

Ant, of course, is far from the only Chinese company targeted by American officials. The Trump administration has also blocked deals for semiconductor and chipmaker companies, as well as a minuscule stock exchange in Chicago. But it is telecom group Huawei that has taken the most heat: the company’s CFO was jailed in Canada for allegedly breaking US sanctions on Iran, and US officials have encouraged allies to ban Huawei’s 5G gear.

Other countries have been more open to Ant’s overtures. In the UK, for example, Ant’s acquisition of WorldFirst appeared to face little blowback (the British payment company closed its US operations to protect the deal). Not coincidentally, the UK also seems cautiously open to working with Huawei to build its telecom network.

Alipay is available in the US, but only for Chinese nationals, such as visiting students and tourists (a lucrative market—they spent $258 billion around the world in 2017). It’s long been speculated that Ant would one day use the infrastructure put in place for Chinese tourists to go after Western consumers. It seems unlikely that that would be permitted however, at least in the US, given that Visa and Mastercard have always been barred from the Chinese market. Ant consistently says its presence in countries like the US is merely to serve Chinese consumers abroad.

Ant has had much more success in Asia, where it has invested in series of mobile wallet companies, from India’s PayTM to bKash in Bangladesh. There, the strategy has been to snap up stakes in dominant payment companies and help them do more, according to CreditEase’s Patwardhan. Instead of rebranding them, the company has encouraged companies to follow the Ant model: If the startup is in payments, then Ant encourages them to get into lending and then, perhaps, chat applications and other services to build out the ecosystem.

Some companies have told Patwardhan that a condition for Ant investment is that, if expansion would mean competing with some other Ant brand, they limit their international scope. “They have big ambitions,” she said.