This story has been updated to reflect China’s Nov. 13 congratulating of US president-elect Joe Biden.

The 2020 US election was a nail-biter that also had far-reaching geopolitical implications; an ‘America first’ vision of the world faced off against a more traditional US foreign policy approach favoring multilateralism.

Many of America’s allies congratulated Joe Biden and Kamala Harris on their election as president and vice president. But others have not. And while boilerplate congratulatory tweets don’t necessarily reveal much about what countries truly think of the results of this election—after all, almost everyone has an interest in working more closely with Washington—in some instances, silence is indicative of which areas of the world a future Biden administration might struggle to work with:

China

At a press briefing on Friday (Nov. 13), Chinese president Xi Jinping offered a belated congratulations to the new US president, almost a week after the race was called. Earlier in the week, China’s foreign ministry was cautious in its statement:

Beijing sees Washington as a rival regardless of who’s in charge there, but the Trump presidency ushered in what many have called a “new Cold War” between the two nations. Trump imposed trade tariffs on China, labeled it a currency manipulator, pressured allies into blacklisting Chinese tech giant Huawei, and ended Hong Kong’s special economic status after Beijing imposed a security law there that limits the territory’s freedoms.

Biden has criticized Trump’s broad tariffs on China as “erratic” and promised to consult allies in order to implement a more targeted approach to resolving trade tensions with Beijing. He pledged to do more to defend human rights in Xinjiang. And he said he would deepen the US’s role and investment in the Asia-Pacific.

But Biden has a long history of dealing with China as former chairman of the Senate foreign affairs committee and later as vice president—and his instincts haven’t always born out. During the early days of his campaign for president he said China is “not competition for us.” And as senator, Biden supported China’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization, a watershed moment for the country that laid the foundation for many of the trade-related grievances the US holds against Beijing today.

China believes that US dominance of the world order is in decline and Beijing may have seen Trump’s polarizing and isolationist presidency as speeding up that decline in China’s favor. But it’s also clear that no matter who is in the White House, the US has woken up to the challenge posed by China’s rise. While a president Biden may help inject some predictability and stability back into the relationship between the world’s two superpowers, it won’t address the underlying tensions.

Turkey

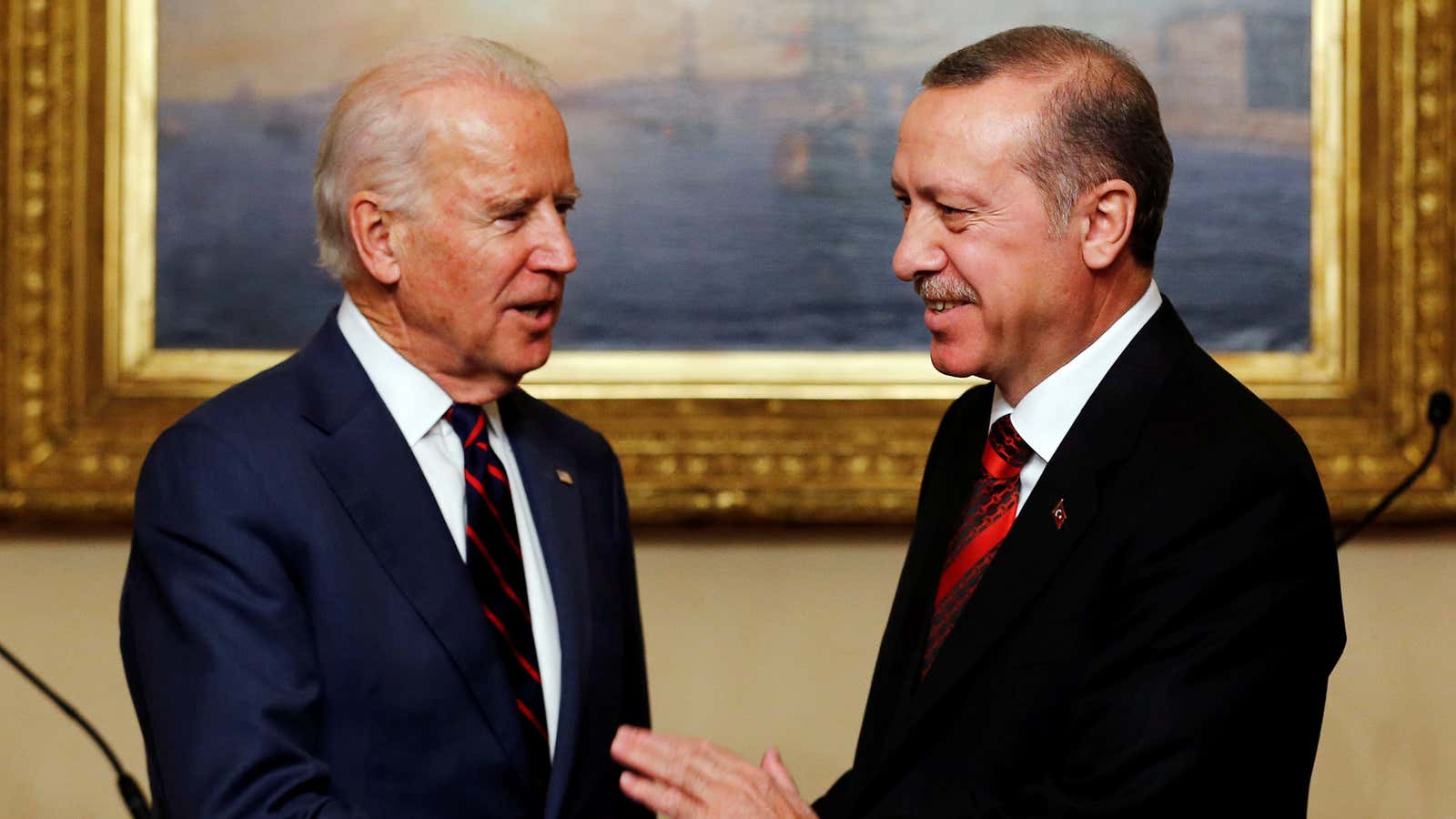

Prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has so far stayed mum on the election. Speaking to Turkish TV station Kanal 7 today (Nov. 9), his vice president, Fuat Oktay, said he would closely monitor Biden’s foreign policy approach. (An opposition leader who congratulated Biden and Harris was criticized by members of Erdogan’s party.)

Turkey and the US have had a tumultuous relationship under Donald Trump that began when he ordered US troops to leave Syria in 2018. Ankara saw that as a betrayal because it would leave vast swaths of territory at its border under the control of US-backed Kurdish militias allied to the Kurdistan Workers’ party (PKK), a separatist group that is one of Turkey’s major adversaries. When Turkish troops invaded northern Syria, the Trump administration imposed sanctions on Erdogan’s officials.

But in 2018, Erdogan released Andrew Brunson, an American pastor who was jailed in 2016 and accused of spying and working with the PKK. This was a personal victory for Trump; Brunson visited the White House and prayed for the president. Trump and Erdogan also had a good personal rapport; the US president told journalist Bob Woodward, “I get along very well with Erdogan, even though you’re not supposed to because everyone says, ‘What a horrible guy.'”

When Ankara bought advanced missile systems from Russia, the US removed Turkey from a consortium of countries building parts of the F-35 jet, an advanced fighter-bomber—but Trump declined to impose sanctions on Turkey.

That is one of the many decisions that a future president Joe Biden is likely to reevaluate as part of his foreign policy pivot. Biden has promised to support Erdogan’s political opposition as well as the Kurds. He called Trump’s withdrawal of US troops from northern Syria “the most shameful thing any president has done in modern history in terms of foreign policy.”

Biden will have to contend with Ankara’s increasingly assertive role in the eastern Mediterranean, where it has territorial disputes with both Greece and Cyprus. Meanwhile, Erdogan’s major bone of contention with any US president is that Washington refuses to extradite Islamic cleric Fethullah Gülen, who Erdogan holds responsible for a failed coup attempt in 2016. There’s no evidence that Biden would approach that issue any differently than his predecessor; if anything, Trump seemed the more likely of the two to bend. In 2018 Turkey’s foreign minister Mevlut Cavusoglu said that Trump “told Erdogan they were working on extraditing Gulen and other people.”

Russia

Analyzing the US’s relationship with Russia under Donald Trump could fill a novel. Suffice to say it’s been controversial.

In many ways, Trump’s goals sometimes overlapped with those of Russian president Vladimir Putin’s. They both wanted NATO to scale back its role in Europe, for example, albeit for different reasons—Russia views it as a threat close to its border and a vestige of the Cold War, while Trump views it as “obsolete” and a waste of US money. The two enjoyed a good personal relationship: “I like Putin, he likes me,” Trump said at a rally (video). Trump also argued that Russia should be let back into the Group of Seven, a group of developed economies from which it was expelled after it invaded and annexed Crimea in 2014.

But that doesn’t mean the Trump administration went easy on Russia. Trump withdrew from a 1987 arms control treaty with Russia, citing noncompliance. He expanded Obama-era sanctions on Russian diplomats, businesspeople, and hackers over various incidents, from the murder of former Russian spy Sergei Skripal in London to Russia’s actions in Syria. And he provided military aid to Ukraine—although ironically, he was impeached in 2019 in part because he used the aid as a bargaining chip to try to pressure Ukraine into investigating Biden’s son Hunter.

Still, it seemed at times like Trump was inviting Russian interference into American political life. After the US Senate’s Intelligence Committee released a report concluding that “the Russian government engaged in an aggressive, multi-faceted effort to influence, or attempt to influence, the outcome of the 2016 presidential election” in favor of the Trump campaign, Trump said he didn’t believe the report because Putin denied it. And when The New York Times reported a Russian military unit offered bounties to Afghan militants for killing American troops in the country, Trump said he wasn’t briefed about it. (Biden called this a “dereliction of duty.”)

Meanwhile Biden supports NATO and believes it should expand to include Ukraine and Georgia. He has suggested imposing more sanctions on Moscow and forming an independent investigation into Russian election interference. He believes the US should lead an effort among its allies to combat Russian cyber-attacks, meddling, and corruption. “Russia’s assault on democracy and subversion of democratic political systems calls for a strong response,” he wrote in Foreign Affairs in 2018.

Putin hasn’t congratulated Joe Biden on his win. News agency Interfax (link in Russian) attributed the following statement to Putin’s spokesperson:

“Anticipating your possible question about Putin congratulating the U.S. president-elect, I want to say the following: we consider it correct to wait for the official summing up of the results of the elections.”

With contributions from Jane Li.