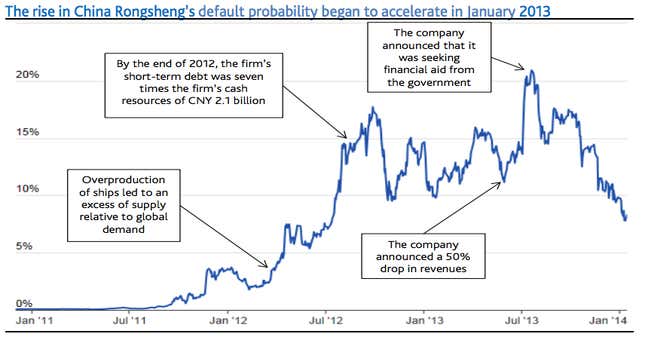

With Chinese steelmakers and solar companies struggling to pay off debts, it was only a matter of time before shipbuilding, China’s other notoriously indebted sector, began flailing publicly. Sure enough, China’s biggest private shipbuilder, Rongsheng Heavy Industries, today announced an 8.9-billion-yuan ($1.4-billion) net loss for 2013 (paywall)—its second consecutive annual loss.

The company, which builds iron ore cargo ships for the Brazilian mining firm Vale, revealed that it is in discussions with 10 banks—including Bank of China, China Minsheng Bank and China Development Bank—to extend deadlines on 10 billion yuan of debt. And that’s just the most urgent batch of loans; its total obligations exceed 22.4 billion yuan, more than half of which is due within 12 months.

Since listing in 2010 on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, the company has lost 90% of its value; it’s now worth around HK$8.9 billion ($1.2 billion), as the chart below shows.

How did Rongsheng get into such dire straits in the first place?

To stave off the effects of the global economic slowdown that followed the 2008 financial crisis, the Chinese government stimulated the economy through trillions of dollars in lending.

This lending boom dovetailed nicely with one of the Chinese government’s stated ambitions: to become the planet’s biggest shipbuilder by 2015. The resulting credit-fueled over-investment in the sector saw China ramp up to 1,647 shipyards as of 2012, compared with the 10 to 15 that South Korea and Japan have, according to Moody Analytics (pdf, p.2).

Rongsheng benefited handsomely; between 2007 and 2012, Rongsheng’s assets leapt sevenfold, thanks in large part to the policy-directed loan bonanza. The company reported impressive revenue growth and fat profits in 2010 and 2011 and continued to expand capacity.

The company has a plan to keep afloat. It’s continuing to slash management salaries, having already cut around four-fifths of its workers in two years. Rongsheng now says it is hoping for a 3-billion-yuan injection from its billionaire founder, who happens to be its biggest shareholder. The company is buying itself some time by issuing convertible bonds. In January, the company sold HK$1 billion in dim sum bonds (debt securities denominated in yuan but issued offshore, typically in Hong Kong). It’s planning another sale in April.

This aligns with one of the company’s top priorities of the moment, said Bank of America/Merrill Lynch analyst Jacqueline Li in a note on Friday—namely, to issue more convertible bonds. It’s a handy way of keeping the cash coming in even as ship orders dwindle. The HK$3.4 billion in convertible bonds Rongsheng has sold since mid-2013 implies a pretty significant dilution of equity, should these be converted to shares. Li notes that its other priorities are rolling over its short-term bank loans and finding strategic investors.