Democrats will control the entire executive branch for the first time since 2011 as Georgia sends two Democratic senators to Congress. The last time this happened, Barack Obama was entering the White House in 2009, backed by commanding Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress.

What followed was a stimulus bill that transformed the US economy in ways that accelerated the clean-energy transition faster than anyone imagined.

The $831 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act earmarked $90 billion for clean energy and climate-related programs. Its massive size, more than 10 times larger than previous clean energy bills, placed thousands of bets on energy efficiency, grid modernization, transportation, and renewable energy technologies across the country. “And it worked, unbelievably,” said Michael Grunwald, a journalist who wrote a book on the 2009 stimulus plan.

History is poised to repeat itself. Joe Biden ran on the most ambitious climate plan in US history, and while he didn’t embrace the entirety of the Green New Deal (Biden has referred to it as a “crucial framework” with the “epic scope” needed to meet the climate challenge), its spirit is reflected in the president-elect’s day one agenda. From redirecting the $500 billion federal government procurement budget to reestablishing methane pollution limits and rejoining the Paris climate agreement, the new White House has planned a sweeping climate term.

Biden’s ability to make good on his campaign promises would have been substantially limited by a Republican-controlled Senate. Now backed by a Democrat-led Congress, the incoming administration will come under enormous pressure to make its agenda even more ambitious during the two years it’s virtually guaranteed to hold the levers of power.

But that doesn’t mean that the greatest ambitions of progressive climate activists will be easily within reach. “This is all good news for Biden, and for the climate and energy community, but we shouldn’t get carried away and think we’ve reached the promised land,” said Alden Meyer, a senior associate at E3G, a climate policy think tank. “We haven’t. A lot of work will be required.”

To start, here are the main climate promises that Biden could be positioned to beef up with congressional backing. This is a wish list of ambitious measures within the realm of political possibility.

Build a new clean economy, and fast

Biden’s campaign presented a 2050 timeline for achieving a net-zero economy, and the White House’s newfound power will likely give it the ability to enshrine that timeline in legislation (only a handful of countries such as the UK, France, and Sweden have done so).

But goals placed that far in the future allow federal leaders and industries to avoid the most painful emissions-cutting changes, like banning petroleum vehicles and phasing out coal. That gives Democrats a reason to push Biden to sign off on more ambitious—and detailed—targets for specific sectors.

Adding an interim goal of halving emissions below 2005 levels by 2030 would give teeth to the mid-century target. The World Resources Institute calls for clean electricity standards to ramp up to 55% by 2025, 75% by 2030, and 100% by 2035. That’s a very ambitious target that that will require accelerated retirement of fossil fuel assets; massive expansion of wind, solar, energy storage; and expanded electricity transmission—not impossible, but the most formidable challenge since electrification of the US itself.

Accelerating that timeline will require big bucks. Biden’s original plan called for a $1.7 trillion package over the coming decade ($7 trillion including private, state, and local investment), paid for in part by rolling back Trump’s tax cuts. Yet the need—and the ease of paying for it given historically low-interest rates, pent-up stimulus demand, and even some bipartisan support—means this figure will likely swell, especially when rolled into infrastructure spending.

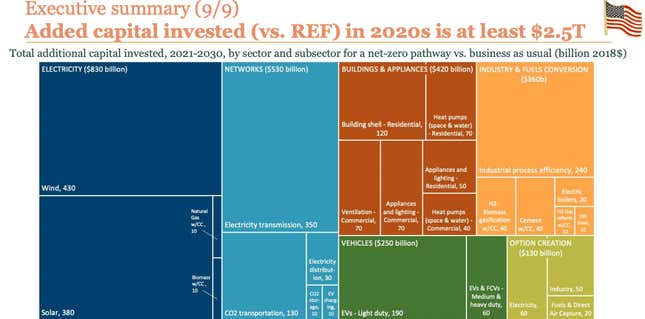

To get a sense of how much that budget could expand, researchers at Princeton University estimated $2.5 trillion will be needed over the next decade to put the US on track to reach net-zero emissions by mid-century (and that’s without decarbonizing major sectors outside steel and cement).

Democrats also want to turn climate into a jobs program. Biden’s climate plan called to “reinvigorate and repurpose AmeriCorps for sustainability so every American can participate in the clean energy economy.” A Republican Senate was never likely to bless funding for a massive new works program around climate change. But now, the Democratic party could make a renewed Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) the centerpiece of its climate efforts.

The original CCC was a New Deal program in the 1930s employing millions of young men during the Great Depression on environmental projects. A modern version could spend billions of dollars to prove climate action delivers good wages and jobs throughout the country. It also happens to poll incredibly well (pdf): 78% of Democrats and 84% of Republicans are in support of it, according to Data for Progress.

Cut industry-specific emissions

Biden’s current plan calls for “accelerating the deployment of electric vehicles” by expanding EV incentives and building more than 500,000 new public charging outlets by the end of 2030. But that’s a modest goal compared to California’s 2035 target for eliminating most combustion engines on the road. This July, 15 states signed on to an initiative phasing out fossil fuels for heavy-duty trucks and buses.

A new federal target to phase out petroleum-powered vehicles could massively accelerate this transition in the US, and Senate leader Chuck Schumer has already signaled he’ll make his “Bold Plan for Clean Cars” a signature issue. A truly aggressive approach to vehicle emissions wouldn’t just support the growth of EVs: It would phase out new fossil-fueled passenger vehicles by 2035 or 2040.

The same ambition can be applied to airline emissions. Biden’s original climate plan called to “target airline emissions…by pursuing measures to incentivize the creation of new, sustainable fuels for aircraft.” But this seems like a clear point for the administration to get on board with Europe and set more stringent targets for aviation.

The European Union is now aiming for “zero-emission large aircraft” to hit the market by 2035, and ensure all short domestic flights are carbon neutral by 2030. Given Biden’s vow to “lead the world to lock in enforceable international agreements to reduce emissions in global shipping and aviation,” stepping up aviation goals is likely to be on the agenda.

Streamline swift climate action in Congress

Democratic control of Congress will decrease the likelihood that federal climate initiatives will come under needless oversight. High-profile, Republican-led hearings in 2011 over the failure of federally-backed solar company Solyndra left a lasting reluctance among bureaucrats in key agencies to push for innovative climate technology and policies, said Adam Zurofsky, executive director of Rewiring America, a clean energy research and advocacy group.

“People have been unwilling to take risks because they’re afraid of being dragged up to the Hill,” he said. “Now Congress can exercise oversight but with less political theater around these issues.”

One of Biden’s first priorities will be to ask the Senate to confirm his nominees for cabinet positions. Biden has assembled a strong bench of climate-focused nominees in a number of departments, including former Michigan governor Jennifer Granholm for Energy, New Mexico representative Deb Haaland for Interior, and North Carolina regulator Michael Regan for EPA. With New York Democrat Chuck Schumer as Senate majority leader, there’s little reason to expect any of these nominees will fail to be confirmed.

Removing Mitch McConnell as majority leader, Meyer said, also decreases pressure on Republican climate moderates like Mitt Romney and Rob Portman to toe the party line, and frees them up to work on bipartisan climate bills.

But what about a carbon tax?

Democrats once faced the prospect of negotiating with Republican leader Mitch McConnell over every bill to clear the 60-vote hurdle presented by the filibuster. That’s no longer true. But Democrats in the Senate are not a unified bloc on climate, and with such a narrow margin over Republicans, they will need every vote.

That makes Democrat Joe Manchin of West Virginia the most powerful senator in the US. Manchin, Arizona’s Kyrsten Sinema, and Montana’s Jon Tester all have mixed environmental records and are unlikely to go as far as climate hawks like Vermont’s Bernie Sanders or Massachusetts’ Ed Markey will want.

This means that passing big economy-wide climate bills like a national carbon tax, moonshots for many climate activists, remain improbable. “Even with a Democrat-led Senate, the Green New Deal and things like it are not on the agenda,” Zurofsky said. “Manchin is not going to go whole hog on that.”

Still, there’s now a much better chance that progressive climate policies and increased funding for climate measures can slip into other bills, the way that groundbreaking restrictions on refrigerant emissions were tacked onto the recent Covid-19 relief bill. The highway bill, farm bill, and others that recur regularly and usually attract bipartisan support could also come to house new climate programs, while existing programs, from the solar tax credit to federal home weatherization loans, can be extended and expanded.

Zurofsky said Biden now has a better chance to integrate climate into all the workings of the federal government, and break through the antiquated stigma around such programs as risky and expensive.

“There’s a real opportunity for programs that are about the climate, but are framed as economic stimulus and have the effect of normalizing what we need for the future so people don’t find it as threatening,” he said.