Covid-19 taught us a lot of new words.

What do you call a global epidemic? Pandemic. What’s the term for when you are trying to stay away from people not out of misanthropy, but to stop a virus from circulating? Social distancing.

And what is the name for concurring epidemics all affecting one region, each making the other worse? That is a syndemic—and it’s what America is in right now.

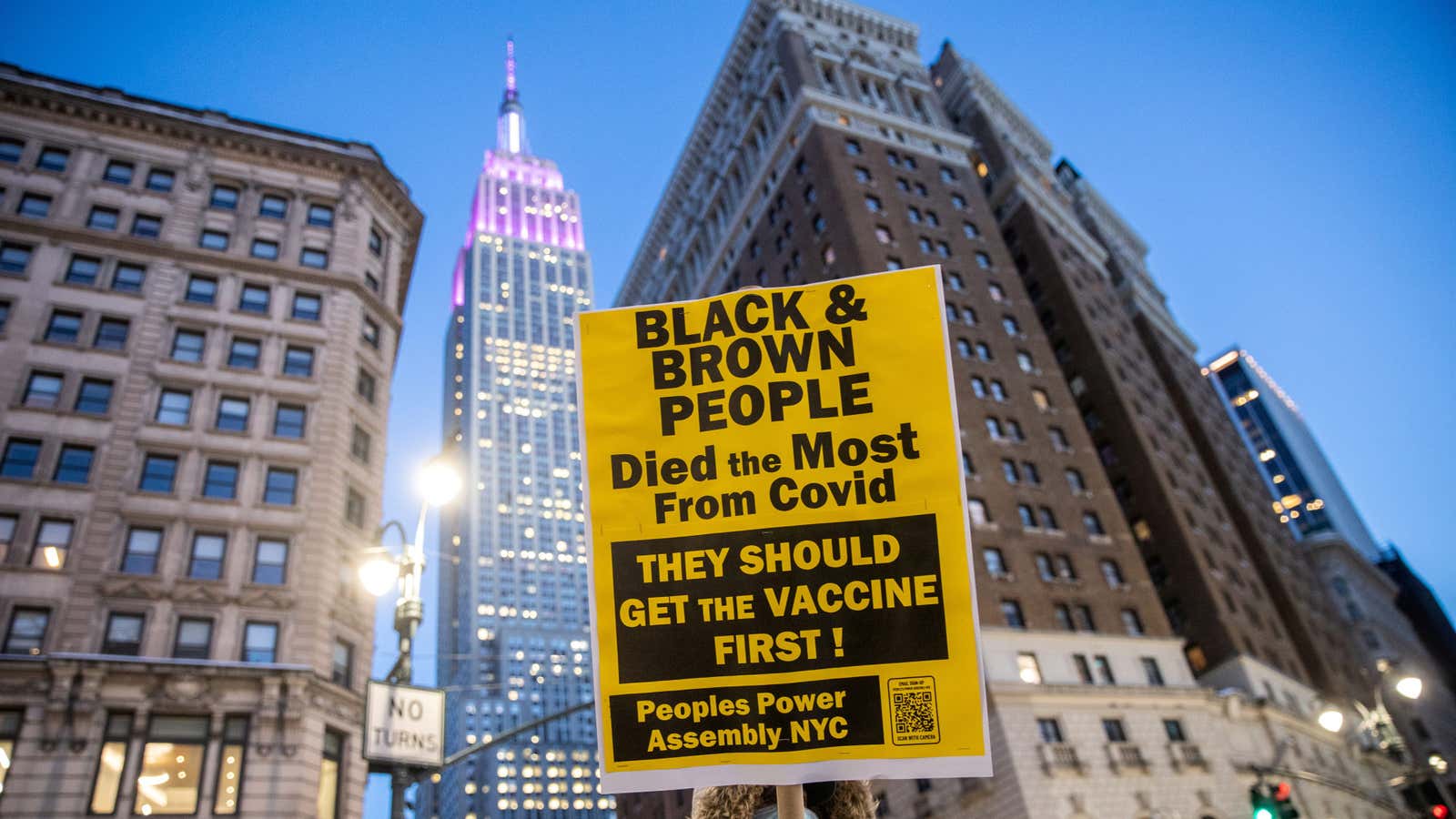

Over 15% of the population has been fully vaccinated, and nearly 30% has received at least one vaccine dose, so the country is beginning to get the coronavirus epidemic under control. Yet its consequences are going to have a long-term impact, particularly because of Covid-19’s interaction with pre-existing public health and social crises—in particular racism and systemic inequalities.

That’s how syndemics work: Poverty or lack of education, for instance, leads to health inequities, and racism worsens them, putting people of color—particularly Black people—at higher risk of chronic diseases and making them more vulnerable to severe consequences of Covid-19. (They’re also more likely to suffer from the pandemic’s financial and social fallout.)

It’s not the first time multiple epidemics and social issues interact. The term “syndemic” was coined by anthropologist Merrill Singer in the early 1990s, who combined “synergy” and “epidemic” to describe “a set of closely interrelated endemic and epidemic conditions” at work during the HIV/AIDS crisis. That epidemic was especially devastating among poor communities of color in urban settings, and hit certain groups harder based on race and sexual identity.

The framework, which has been applied to other intersecting public health issues, has the unique advantage of looking at the way underlying social issues worsen health conditions. For example, Emily Mendenhall, professor of global health at Georgetown University, used the syndemic model to understand the intersection of mental health and diabetes with sexism, xenophobia, and poverty among Mexican immigrant women. Instead of simply looking at the prevalence of medical conditions, she identified how those socioeconomic factors made the group more vulnerable, leading to higher mortality and worse health in general.

This way, policymakers can widen their focus beyond merely solving a health crisis to also tackle the causes of inequality that make certain communities suffer disproportionately. The impact of this approach is long-term, too—by strengthening these communities, society at large will be better prepared in the face of the next health crisis.

“There is a temptation to think of AIDS as a medical problem, to think of Covid-19 as a medical problem, and part of the point is to say they are medical problems but not only—and maybe not even primarily,” says University of Florida anthropologist Clarence Gravlee. “Covid-19, as HIV/AIDS, reflects the dynamics of power inequality in society.”