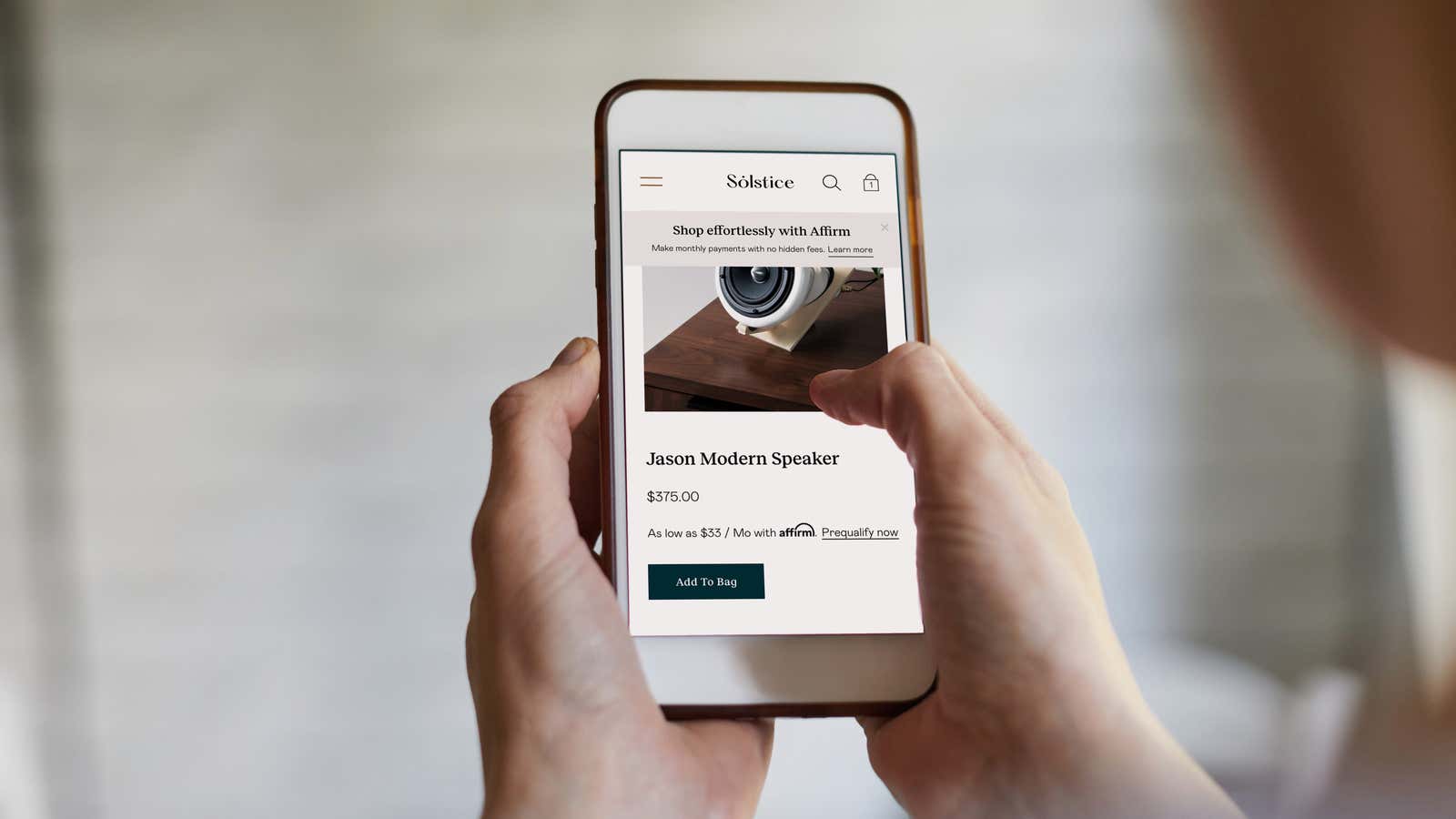

Affirm is one of the companies at the forefront of “buy now pay later”—the slick digital lending that’s growing in popularity with Gen Z and millennial shoppers. Nearly a decade since Affirm was started, the BNPL business model is dogged by questions about whether its claims about being interest-free and not charging late fees are too good to be true.

Those questions are increasingly important as pay-later services from the likes of Affirm, Klarna, PayPal, and Afterpay become entrenched and go head-to-head with the $8 trillion credit card industry. In Australia, there are signs of younger consumers who have never filled out a card application getting in over their heads with these types of offerings, according to a regulatory review (Affirm wasn’t included in the review). And merchants, who may have to fork over some 3% to 6% of the transaction to the pay-later lender, have to decide whether putting these services on their checkout is worth it. (You can read more about the ins and outs of BNPL—a catchall term for point-of-sale and pay-in-four loans—in this story).

Affirm CEO Max Levchin insists his company is different. The PayPal co-founder says Affirm only collects interest about half the time and that it never charges late fees. He says this forces Affirm to underwrite loans carefully, because otherwise it stands to lose money. As for merchants, he argues that Affirm is well worth the expense because it can boost the amount of money customers spend and can bring them back more often. He says this will help Affirm withstand a competitive land-grab phase as these lenders fight for market share.

Quartz spoke with Levchin about the risks inherent in BNPL lending and customers’ “revenge spending” as the economy opens up. The conversation was edited and condensed for clarity.

Quartz: How do you make sure your customers haven’t stacked up borrowing from multiple different lenders so they can’t afford to pay back their loans? The risk seems like a consumer version of the Archegos meltdown, in which the family office had borrowed from a bunch of different investment banks that may not have had insight into Archegos’ total amount of leverage and risk.

Levchin: I’m chuckling at the comparison. The aggregate scale of BNPL may be reaching the size of Archegos but we’re a little way off.

I obviously can’t speak to how our esteemed composition insures against this, but this is something that obviously we have to care about. We don’t want the consumer to overspend, and equally it’s important that the consumer is not overextended.

We aligned ourselves with the end consumer, the end borrower, at a very, very fundamental level. We don’t charge late fees. We don’t have any fees other than interest where applicable and half the time there’s no interest at all. So fundamentally, if the consumer is late, if they need to take some extra time or if they say, you know what, sorry, I’m just not paying you, we get nothing.

And that’s by design in the sense that we want to be completely aligned with the end borrower.

It’s on us to do the necessary underwriting to get the right kind of data. We certainly are very careful to not say out loud exactly where and how we do our underwriting, since that’s the part of our competitive advantage. But it is something that’s really important to us. And I believe that our model primes us to be strictly on the side of the consumer.

Could you imagine a world where regulation required transparency to avoid that problem?

I’m generally pro thoughtful regulation. It is very possible to imagine a thoughtfully written regulation requiring some form of reporting, and I think that’s never a bad thing so long as it doesn’t constrain innovation and thoughtful but useful behavior by the innovators.

This is a little pre-historic times, but I spent a bunch of years on the advisory board at the CFPB [Consumer Financial Protection Board], and my takeaway from that was it’s incumbent on the tech industry to speak with the regulators more, not less.

The lower engagement strategy with the regulators, especially in financial services, is just a silly, stupid idea. And the fact that we were so open in our dialog with CFPB and continue to maintain contact with all regulators out there has generally been helpful to us. We understand what their purposes are. I think they understand what our mission is.

Speaking for myself, I’m always excited to engage with regulators because I get to tell them all the things that we have going on and hopefully get their support. So in that sense, I welcome the engagement. Of course, there’s plenty of examples that I’m sure someone can provide of regulation that stifled innovation. And obviously one has to be conscious of that. But I think that can and should be addressed through dialogue.

There’s a growing number of pay-later type offerings. How do you outcompete the others and make sure Affirm is one of the two or three that gets listed on the checkout?

Probably the most important thing, from my point of view, is just staying true to our message and the mission.

People take a different financial services provider based a little bit on what the merchant accepts and a little bit on their own affinity and a little bit on overall availability. I’m sure Diners Club probably has exceptional rewards, but I haven’t seen that logo in a really long time. So I think that the merchant availability is in fact an important component of further merchant availability. Obviously, we announced our partnership with Shopify to that end and we expect to get fairly good visibility and broad acceptance in that domain. We continue to partner and announce fairly major merchant acceptance, but I feel like we don’t really speak enough to this, so I’ll beat this drum a little louder: We are very different.

We speak to our end customer with the message of both spending and buying things that they deserve, they love, they want, and feeling good about it. Not just from the emotional dopamine hit, of “wow, I have these shoes I’ve always wanted them,” but I actually feel pretty good about making this decision. I feel responsible, I know Affirm has my back and should I stumble, should I miss a date, I won’t get tricked up, and 0% isn’t going to flip and become some gargantuan number going back in time and all the awful things that the industry stands for.

When we started the company a decade ago it was sort of like, “OK, well you guys are crazy, there’s money to be made on late fees, so we’ll wait for you to learn it.” At this point we’ve been at it for long enough that people know we mean it and consumers seem to care about it and, as a result, merchants seem to care about it.

As things seem to be gradually opening up in the US economy, and the jobless rate seems to be declining a bit, what are you seeing in customer behavior?

We survey our customers all the time trying to figure out what is the next big thing they need to think about in terms of buying, and how do they think about all the macroeconomic trends.

We’re seeing some revenge spend from a fair amount of people, and specifically in travel. The thing that people are really primed for, at least according to our surveying, is this: I’ve really been cooped up in my four walls for the last 13 months, or whatever it’s been, seems like 13 years, and I’m going to get out of town and I’m going to go somewhere.

Our survey indicates, and this is within our user cohort, so some skewing younger, etc. But half the people are planning to travel this year and almost 70% are planning to spend significantly more, quote unquote, than their typical budget.

What is your message to merchants if they’re wondering whether the 3% or so that they’re paying to Affirm is too steep for them?

We think of ourselves first and foremost as a marketing platform and a revenue accelerator. We help in conversion in a sense that part of it is access to capital for the end customer. Part of it is, and this is where this idea of not charging late fees and being super fastidious about what it is we’re telling our users, disclosing everything, being over-the-top clear and transparent, helps the vast majority of our customers when we survey them about what made them choose Affirm.

So that in turn results in increased average order value and by increased I mean, it goes up 85%, which is, practically speaking, instead of just buying the shoes, you buy the shoes and the dress, which I think a lot of merchants really, really appreciate. There’s about a 20% increase in repeat purchase rates at the same merchant, which is something that obviously merchants deeply care about. The second sale is almost more important than the first sale.

You mentioned that the average order value can go up by about 85%. Why is that? Are people buying three pairs of shoes and planning to return two of them?

It’s certainly very distributed in terms of the type of merchant. So, for example, if you look at something like Peloton, it’s unlikely you’ll say, you know what, I’ll take two. Some people are, I think, multi-Peloton families and we thank them for the business.

But most of the time, I think it’s just really about increased conversion, increased feeling of safety and, frankly, getting a zero interest or an interest-free transaction. That’s one motivation.

A fair amount of times, it really is about putting putting together an ensemble of clothing or items that you wanted. We don’t see a major impact on returns, which I think is what you were going to on your question.