India’s PM will meet with leaders of all 27 EU countries to talk about … trade?

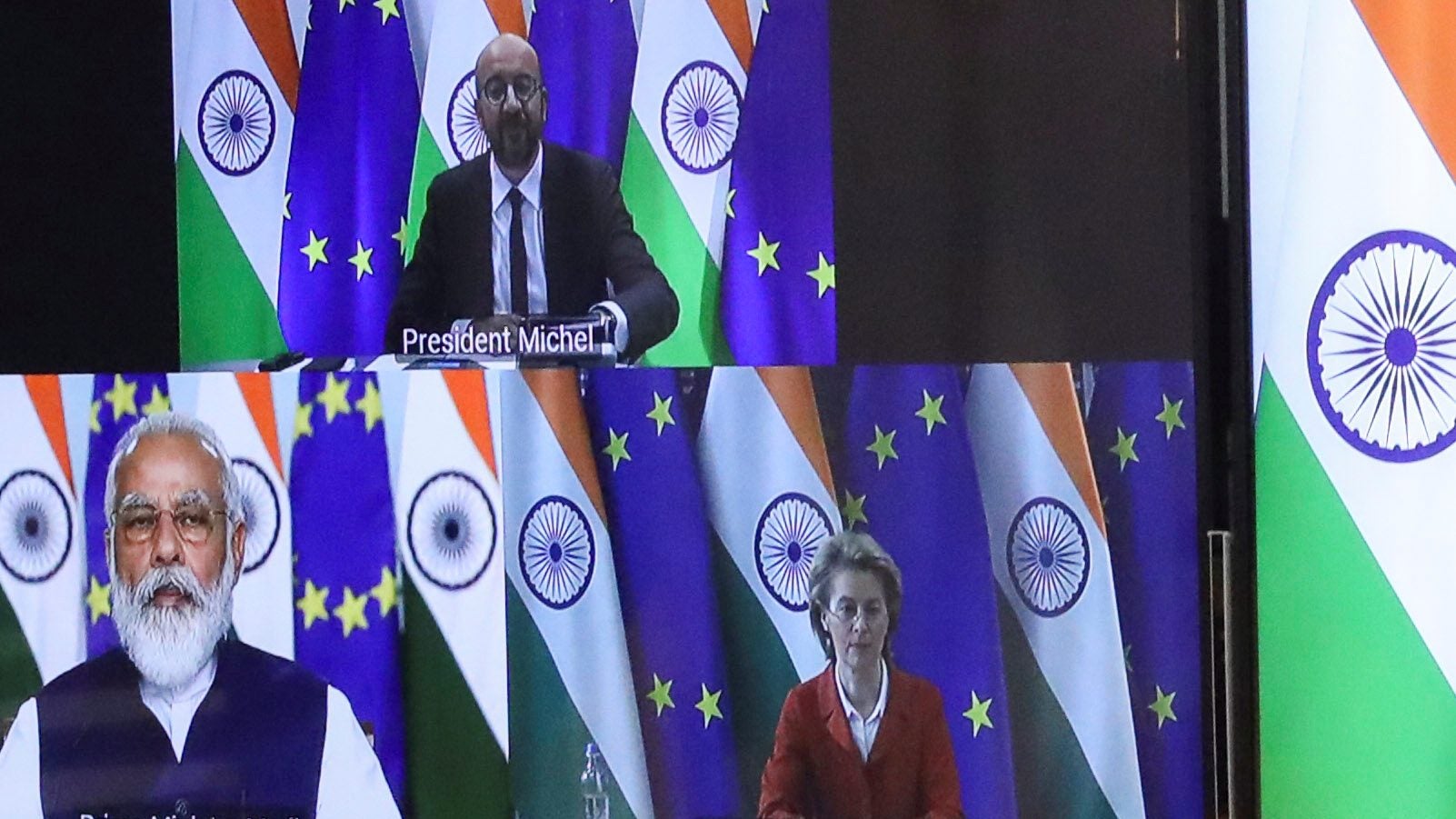

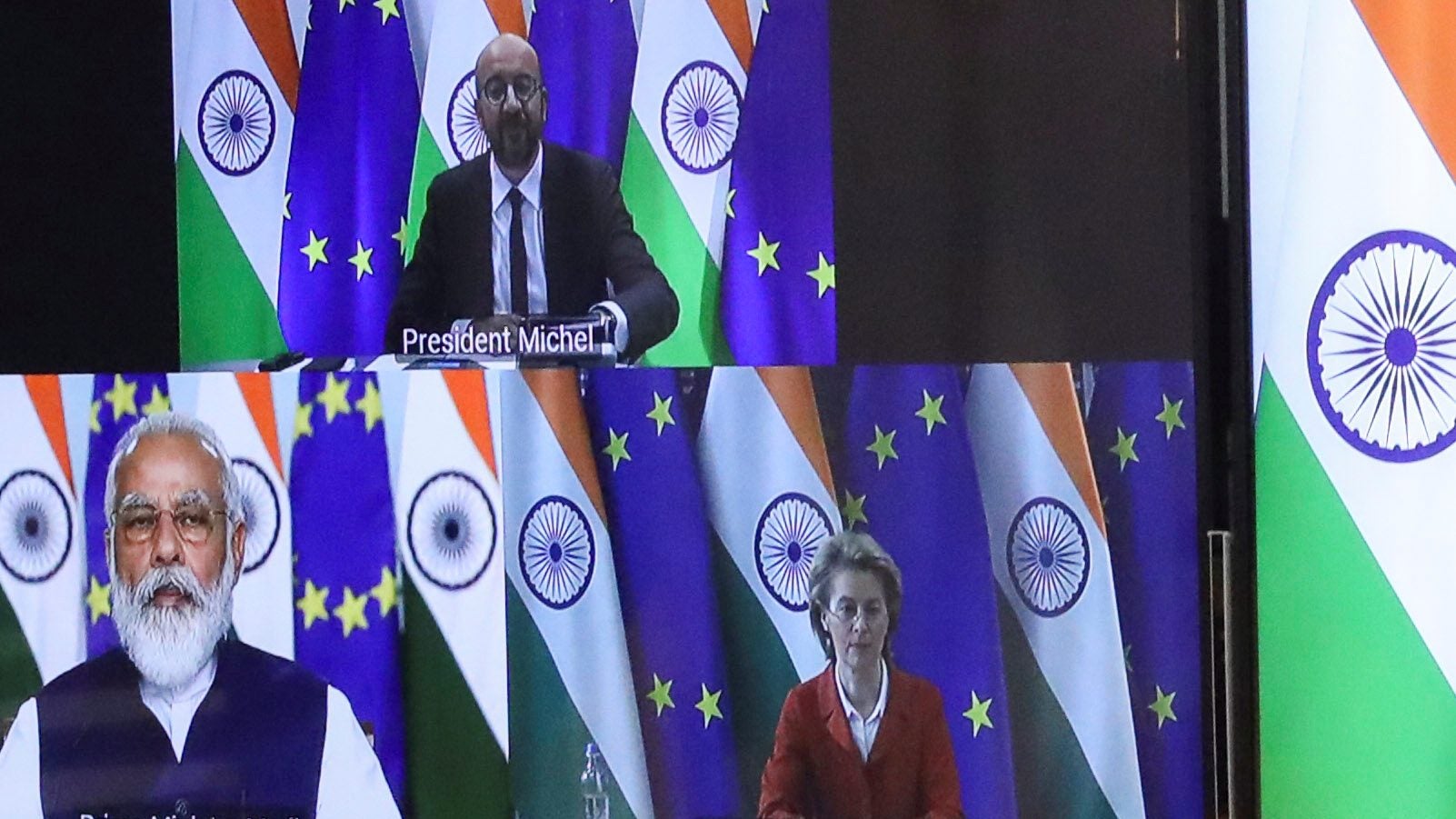

The leaders of the European Union are meeting in person for the first time this year at a summit in Porto, Portugal, on May 7 and 8. On the second day, they’ll be joined (virtually) by a special guest: Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister.

The leaders of the European Union are meeting in person for the first time this year at a summit in Porto, Portugal, on May 7 and 8. On the second day, they’ll be joined (virtually) by a special guest: Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister.

You might be wondering what Modi is doing there—and how he has the time. Conservative estimates show that more than 400,000 people are testing positive for Covid-19 in India every day, the largest single contribution to global infections in the world. ICUs are out of beds, oxygen tanks are rarer than oxygen scams, and rickshaws are being converted into ambulances. For Modi, who has been accused of fueling this humanitarian crisis by encouraging people to gather in large groups, the optics of showing up, even virtually, for a far-away summit, are especially tricky.

Modi’s participation is a sign that he’s determined to keep Indian diplomacy on track, even as calls for him to resign escalate at home. Brussels and New Delhi have decided that they want to work closer together on data privacy standards, climate change, and more. They recently launched a high-level dialogue on trade and investment, and at this summit, they’ll likely discuss a joint strategy on China and the Indo-Pacific region, plans for COP26, and possibly more medical aid for India.

They’re also expected to resurrect talks for a free-trade agreement that were dropped in 2013. In November 2020, India declined to join other Asian countries in forming the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, because of tariff disputes and tensions with China. As a result, “there is a mood in India that they need to be looking West for trade opportunities,” says Garima Mohan, an expert in EU-India relations at the US German Marshall Fund. (The EU is India’s largest trading partner.)

Mohan believes that a bilateral investment treaty, like the one the EU signed with China recently, is more likely than a free-trade agreement, because the two sides still have to resolve disputes over human and labor rights, among other things. The EU, she says, is “still feeling burnt from last time,” but as it looks to diversify supply chains away from China, it sees India as a possible alternative.

It’s not just the EU that India is courting: Modi met virtually with UK prime minister Boris Johnson this week to lay the groundwork for a possible free-trade agreement.

Modi seems determined to plow forward in the middle of a political and public health crisis. But despite his government’s best efforts, reality is intruding: When Indian diplomats traveled to London this week for a meeting of foreign and defense ministers ahead of the G7 Summit, two members of the delegation had to self-isolate after testing positive for Covid-19.