May 12 is the last phase of voting in India’s general election, and over 90% of the country’s voters have already gone to the polls. At this late stage in many democratic contests, statistics gurus would be feverishly crunching the exit and opinion poll numbers to offer up a semi-credible prediction of the results. But India’s national elections have always been more a black box than a horse race, given the influence of local politics and the lack of credible voting analysis.

This time around, the results seem less predictable than ever, with a third party in the form of the Aam Aaadmi showing unexpected strength, voting in individual states not turning out the way it was expected to, allegations of malpractice prompting re-voting and confusion about which candidate is going to be helped by record high voter turnout.

There are a few things we do know, though:

Don’t trust the opinion or the exit polls

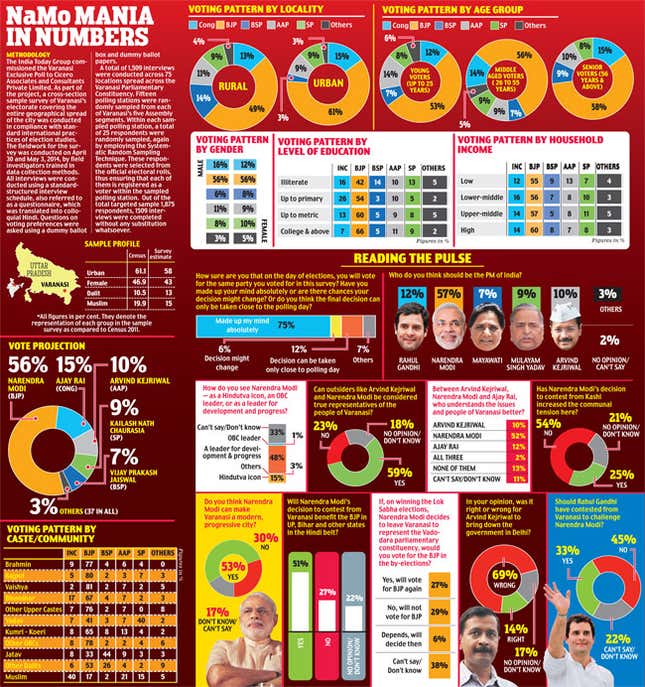

Sure, based on early opinion poll data mostly taken before voting started, India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by Narendra Modi, was predicted to sweep the upcoming national elections so soundly that the results were described as a “thumping victory” for the party and the “worst-ever defeat” for the incumbent Congress Party. The latest opinion poll in the hotly contested state of Varanasi, taken by AAJ Tak, promises the BJP will win by “leaps and bounds,” and is accompanied by an incredibly bullish “NaMo Mania in Numbers” graphic:

There’s little argument that the BJP has run a forceful and effective campaign, and the Congress Party a particularly lackluster one, or that Indian voters are hungry for a change in national leadership.

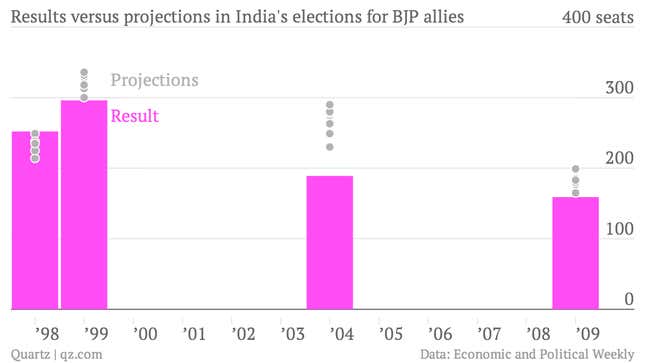

But India’s election opinion and exit polls, as conducted by the country’s big media houses, have been profoundly wrong in two of the last four national elections—and in each of the last three they have significantly overstated the expected votes for the BJP and its allies, as data collected by Economic & Political Weekly shows:

The results above for 2004 and 2009 include not just the opinion polls, but the exit polls as well, which will be broadcast on the evening of May 12, after voting closes.

Opinion and exit polls have been so inaccurate so often in the past that not only are they not taken seriously by analysts, but many in the general population believe they are wrong on purpose in an attempt to curry favor with politicians.

Election opinion polls are viewed in India as “covert instruments used by media houses in collusion with political parties for falsely predicting their fortunes with the aim of influencing the electorate in India,” said Praveen Rai, a political analyst with New Delhi’s Centre for the Study of Developing Societies.

In the last national election in 2009, for example, television network NDTV, Hindi channel Aaj Tak, and media house Zee News predicted based on opinion and exit polls that the BJP and its allies could get between 230 and 250 seats, and Congress and its allies between 176 and 205. The actual number for the BJP group was 189, and Congress and its allies got 222.

The magic number is 272

India is divided into 543 constituencies headed by a member of parliament, and to form a government any given party or coalition of parties needs a simple majority, making 272, the “magic number” of seats. If a leading coalition gets less than this simple majority, it can try to ally with other parties to get to the 272 figure—a generally unstable arrangement, and one that the Congress Party is banking on to give it a chance to return to power in coming years.

NDTV, which runs one of the country’s biggest English-language channels, published one of the most optimistic polls about the outcome for the BJP and its allies on April 15, predicting the group will win 275 seats—a figure that would allow it to form a government alone, and avoid all the messy and unstable alliances. If that happens, it would be a resounding victory for the group and allow the BJP to steer the central government somewhat—although they’ll still have to get any new laws past the second house of Parliament. (More on how India’s parliamentary system works here).

Asked about the NDTV’s opinion poll record in recent elections, head of corporate communications Manisha Natarajan said in an email the company had “never, ever” been pressured by a political party to report a certain opinion poll result. The company has explained its polling methodology completely online, she said, and added “NDTV’s polls have always been unbiased, and we have no political affiliation.”

Still, the NDTV prediction raised eyebrows when it was made, and recently after it was reported that the head of NDTV’s polling partner was a formerly an executive with the PR firm that has represented Narendra Modi’s Gujarat government for years.

Journalism has been muzzled

Ahead of this election, there have been numerous reports that journalists with negative things to say about the BJP or Modi have been pressured by editors and publishers to tone down their coverage, or leave their jobs.

“Reporters are being asked to pipe down; editors are losing their jobs; prime-time programmes are going off air; commentators are replacing vitriol with neutral ink while writing on Modi,” Outlook Magazine reported earlier this year.

Resignations from high-level positions at Indian media houses in recent months have been linked to pressure to cover the BJP or Modi in a positive light, including India TV’s editorial director, the former editor of Open Magazine, a popular talk show host and the former editor-in-chief of The Hindu, whose apartment caretaker was assaulted in Delhi this year, reportedly for the editor’s outspoken comments against the BJP.

The impact may have been an artificial inflation of the popularity of the BJP, some analysts and columnists believe. As Nilanjana Roy wrote recently in The New York Times:

I am skeptical of the media stories that predict an outright victory for the B.J.P., in part because of the drop in the freedom of the Indian press over the last 10 years. Reporters in the Hindi-language media I spoke to privately didn’t doubt the consolidation of support for the party, or Mr. Modi’s charisma, but they felt, as I do, that the riots that took place in Gujarat in 2002 during Mr. Modi’s watch as chief minister have left their mark of distrust and fear, diluting some of the enthusiasm for the growth he promises to achieve. The possibility of a coalition government is not so far-fetched.

Ultimately, learning who India has really voted for will need to wait until May 16, when the election results are released. But history tells us it would be practical to discount predictions of a sweeping victory for the BJP.