HKEX is key to China’s plan to internationalize its economy

The first day at a new job is always stressful, but for Nicolas Aguzin, perhaps especially so. On Monday (May 24), the 52-year-old banking veteran took over as the new CEO of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing (HKEX), the operator of the stock exchange crucial to Hong Kong’s role as a world financial hub.

The first day at a new job is always stressful, but for Nicolas Aguzin, perhaps especially so. On Monday (May 24), the 52-year-old banking veteran took over as the new CEO of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing (HKEX), the operator of the stock exchange crucial to Hong Kong’s role as a world financial hub.

Hong Kong’s identity has long been closely tied to its status as a financial center, and the city’s eponymous (and sole) stock exchange is an integral part of that enterprise. Last year, the exchange was the world’s second largest bourse in terms of IPO funding. Although it also has assets such as the London Metal Exchange, HKEX has almost become the equivalent of the bourse, its most high-profile subsidiary.

After years at JPMorgan Chase, Aguzin is now inheriting a wealth of HKEX-specific challenges, including attracting foreign investors while navigating expectations from Beijing. At stake? Only cementing HKEX’s leading role among exchanges globally. No pressure.

What is HKEX?

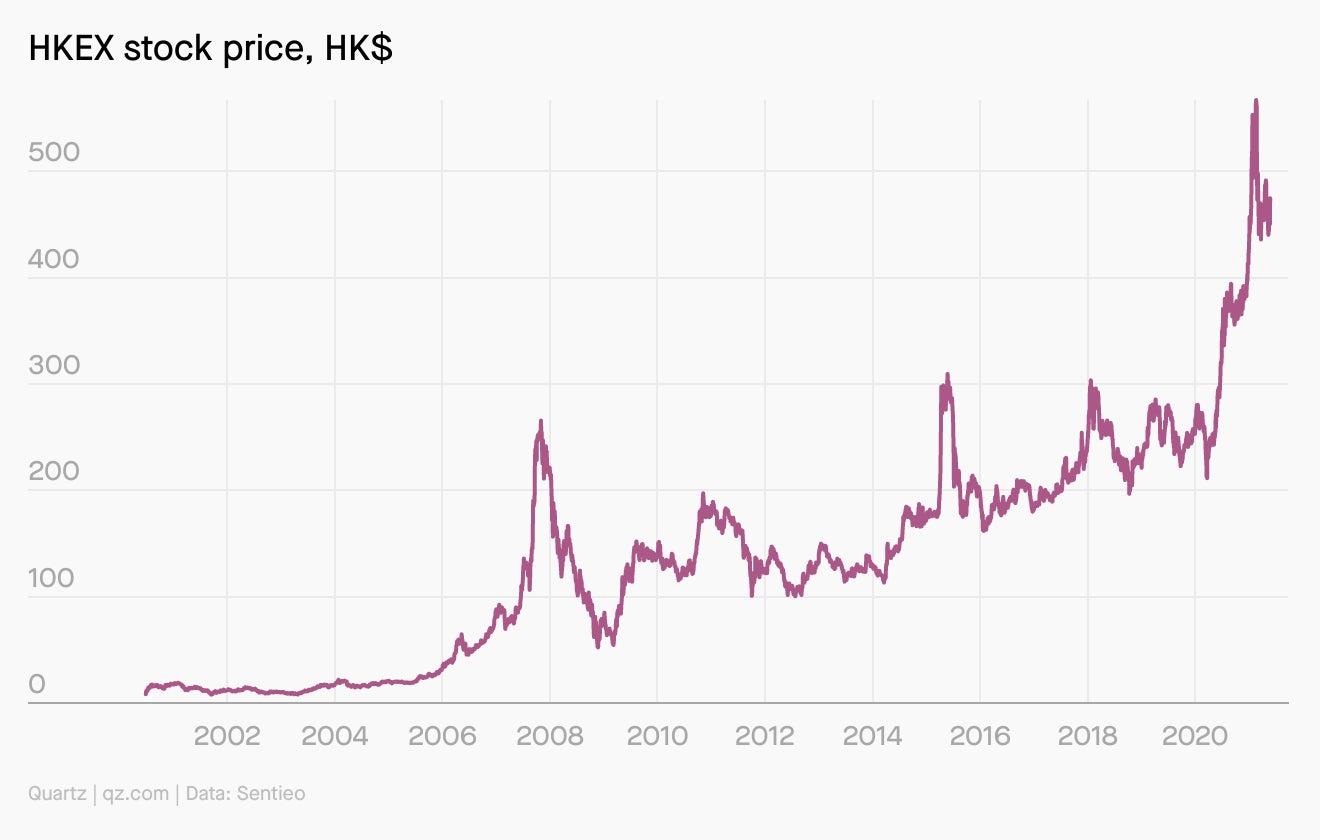

HKEX plays a critical role in China’s ambitions to internationalize its economy. Heightened geopolitical tensions have seen numerous US-listed Chinese companies blacklisted and potentially booted off American exchanges. That has sparked a rush of “homecoming listings” in Hong Kong, pushing up HKEX’s share price, setting record highs in trading volume, and bringing soaring profits.

But uncertainty also looms. Beijing is conducting a full-scale authoritarian crackdown on Hong Kong, partly by implementing a sweeping national security law. Civil liberties, the free press, the rule of law, and an independent judiciary are all being rapidly dismantled—and with them, potentially Hong Kong’s status as an international financial hub. Meanwhile, the Hong Kong government—increasingly beholden to the central government in Beijing—is HKEX’s single largest shareholder.

A more significant shakeout is also possible: Sanctions from countries including the US over Beijing’s behavior in Xinjiang and Hong Kong could give rise to a full US-China decoupling, which in the extreme might lead to separate dollar and yuan financial systems and turn Hong Kong into a purely Chinese financial center. That would fundamentally change HKEX’s role.

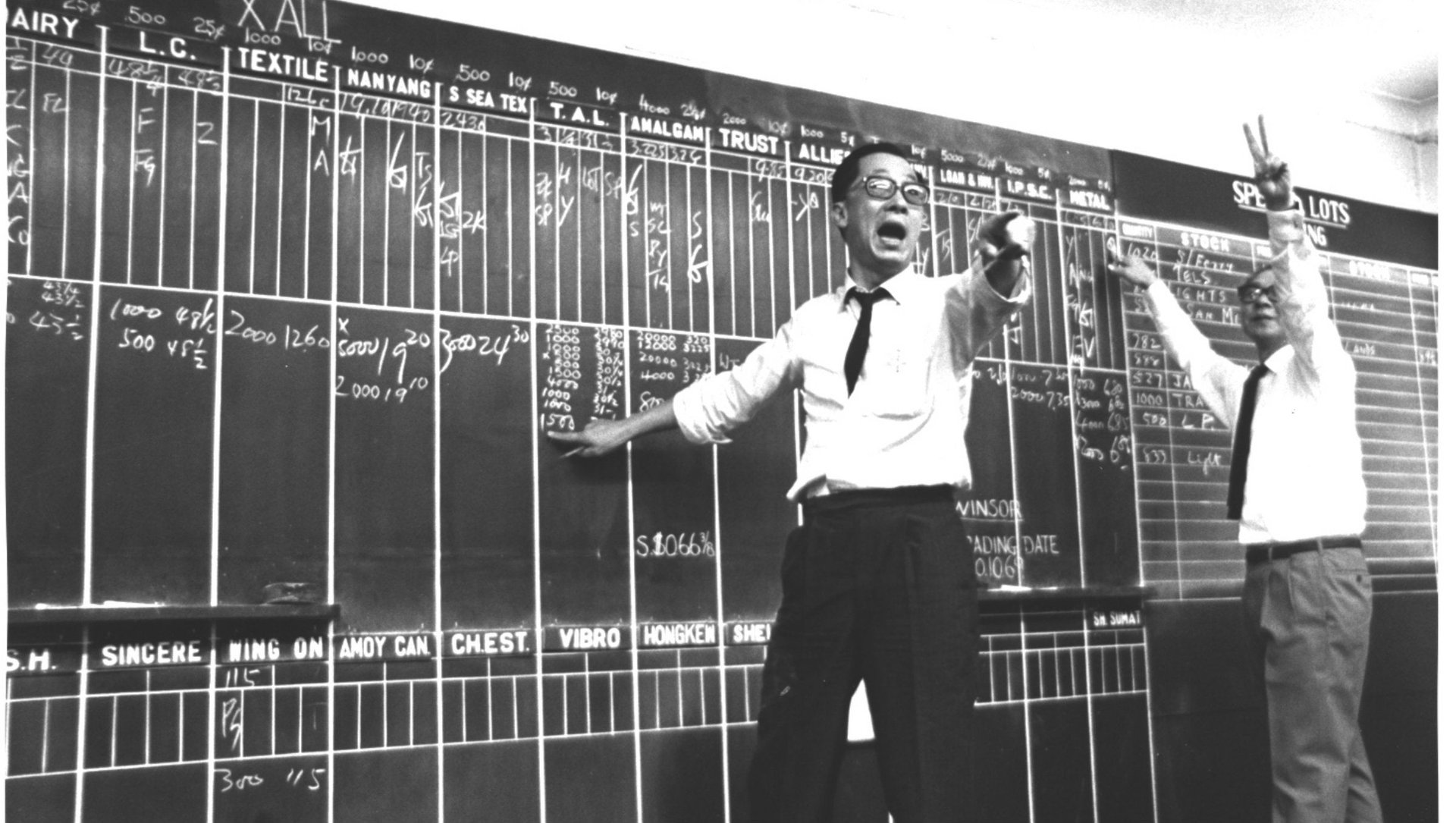

A brief history of HKEX

1999: Hong Kong reforms its stock and futures markets, merging three exchange, futures, and clearing companies to form HKEX.

2012: HKEX buys the London Metal Exchange.

2014: “The Stock Connect” launches, linking HKEX with its Shanghai counterpart.

2018: HKEX introduces dual-class shares, giving some corporate shareholders greater voting rights in a bid to attract more tech giants.

2019: HKEX launches a failed bid to acquire the London Stock Exchange.

2019: Alibaba’s secondary listing is the first of HKEX’s big homecoming listings.

2020: Ant Group files for a concurrent listing on HKEX and Shanghai’s STAR market in what’s expected to be the biggest IPO ever, only to see the flotation later suspended by Beijing.

2021: The Hong Kong government increases a tax rate on stock trading as part of its budget plan to boost revenue, causing HKEX shares to plunge.

HKEX is “China anchored” by design

Just like Hong Kong itself, HKEX has long been an important venue for mainland Chinese companies to tap international investors. Due to Beijing’s tight capital outflow controls, Chinese firms cannot exchange or transfer dollars freely, whereas they can do so in Hong Kong with the help of exchanges like HKEX. In fact, being “China anchored” is a key component of HKEX’s strategic plan, as it positions the bourse to facilitate “China’s internationalization and investment diversification.”

Since 1993, when Tsingtao Brewery became the first mainland Chinese firm to list in Hong Kong and overseas, a growing number of Chinese companies have flocked to the city. With what are known as “H-shares,” where H refers to “Hong Kong,” these companies can trade in a free market and be on equal footing with their international counterparts. The number of listed H shares increased from six in 1993 to 273 as of May 26, 2021. HKEX has also benefited from the breadth of Chinese listings, which helped it move beyond hosting real estate and financial firms and toward attracting cooler, more innovative companies from China.

A further push for HKEX to lean closer to the mainland came from former CEO Charles Li Xiaojia, who spent a decade at the helm before stepping down in December. China-born and US-educated, Li introduced schemes that allow limited stock and bond trading between the exchange and its counterparts in Shanghai and Shenzhen. Li’s grasp of the appetites of both foreign and Chinese companies and investors helped the bourse to flourish. Today, most of China’s tech champions have either a primary or secondary listing in Hong Kong, including Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, and JD.com.

But Beijing’s abrupt halt of Ant Group’s $37 billion IPO in November, only days before its debut in Hong Kong, highlighted that the opportunities presented by the lucrative Chinese market are also huge risks. HKEX’s increasing reliance on Chinese companies could one day become its biggest nightmare.

By the digits

HK$10 million ($1.3 million): Aguzin’s base salary, 7.4% higher than that of his predecessor

0.13%: As of August, Hong Kong’s stamp duty on the value of listed stock trades—up from 0.1% currently

HK$3 billion ($386 million): New proposed minimum valuation of a company in order to qualify for a secondary listing on HKEX, down from the current minimum of HK$40 billion

80%: Percentage of total market capitalization of China-domiciled firms listed on HKEX

10%: The Stock Connect’s contribution to HKEX’s total revenue and other income in 2020 (pdf)

6%: The size of the Hong Kong government’s stake in HKEX, where it is the single largest shareholder and can appoint six of the exchange’s 13 board members

Who is Nicolas Aguzin?

An Argentine who has spent his entire banking career at JPMorgan Chase, Nicolas Aguzin kicked off his tenure at HKEX on Monday. Here’s what you need to know:

🤝 The search for a new CEO wasn’t easy. That’s partly because Aguzin’s predecessor—dubbed “Mr. China”—excelled at courting Chinese and foreign officials, and even the press, with his fluent Mandarin and English. While Aguzin speaks Portuguese and Spanish in addition to English, he reportedly doesn’t speak Mandarin.

📈 Aguzin is expected to help make the bourse attractive to foreign investors, even as Beijing’s campaign of repression threatens to scare businesses away.

💰 Investors and analysts are also looking to the new chief to diversify HKEX’s revenue streams and expand the types of products it offers.

🌏 The choice of Aguzin to lead HKEX was a shrewd one, and sends a clear message, wrote Matthew Brooker of Bloomberg: “Hong Kong remains a place of opportunity for international business executives, amid a news agenda dominated by stories of residents fleeing the national security law imposed on the city by Beijing last year.”

Keep learning

- Who is Nicolas Aguzin, the former JPMorgan banker set to lead Hong Kong’s stock exchange operator? (South China Morning Post)

- Meet Charles Li Xiaojia, the mastermind of Hong Kong’s £32bn swoop for the London Stock Exchange (The Telegraph)

- Hong Kong’s attempted buyout of London Stock Exchange is the most audacious in history (Quartz)

- A tidal wave of Chinese money is causing chaos in Hong Kong’s stock market (Quartz)

- The Hong Kong stock exchange on Beijing’s influence and staying relevant after Alibaba (Quartz)