HONG KONG—It used to be considered the corporate world’s gateway into China. Today, it’s the other way around: Hong Kong is becoming the exit through which pent-up Chinese money and cash-hungry Chinese companies are unleashed on the world. And that means big risks to long-time investors in the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

Mainland Chinese companies have been listing in Hong Kong in growing numbers in recent years, but what really opened the floodgates was the carefully calibrated launch of the “Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect” last November. This, a partnership between the Hong Kong and Shanghai exchanges, allows traders registered on each exchange to invest in stocks on the other. That allows cash-rich Chinese investors to bring billions of dollars out of the country legally, and gives foreign investors unfettered access to public companies in the world’s second-largest economy for the first time. It’s a linchpin of president Xi Jinping’s economic reforms.

The result has been a boon for Hong Kong. The tidal wave of money from mainland China has brought Hong Kong stocks to record highs. IPOs in China and Hong Kong so far this year have raised $63 billion, almost double the figure this time a year ago. And there’s more such money to come—Beijing plans to add a similar link between Hong Kong and Shenzhen, where the equity markets are even more volatile, as soon as this quarter.

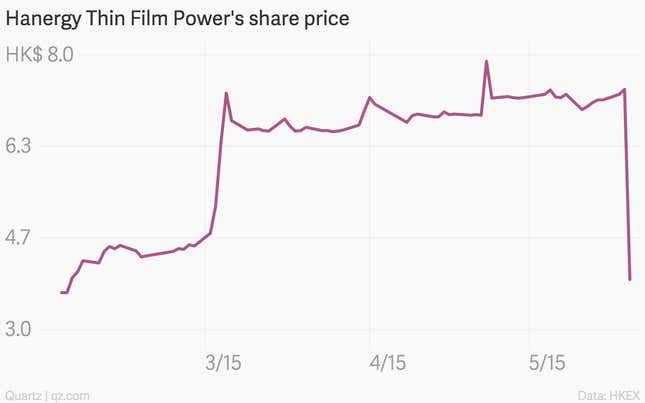

But with the flood of money has also come whiplash volatility. The best example of that is the recent debacle surrounding Hanergy Thin Film Power, a mainland China company that trades in Hong Kong. Just a few months ago, Hanergy was one of Hong Kong’s biggest stocks by market cap (it was briefly worth more than Tesla). Then on May 20, it stopped trading after mysteriously falling 47% in a matter of minutes. Hong Kong’s market regulator, in an unusual public statement, said a week later it was investigating the company, but since then there has been no news.

Investors in Hanergy—who include Quebec civil servants and US teachers—are are now sitting on suspended stock with a face value of HK$163 billion (US$21 billion) that might be worthless. And nobody knows when—or if—trading might recommence. Hanergy, which suspended the trading itself pending an announcement of “inside information,” has still not made one nearly a month later. Hong Kong’s rules about trading suspensions are vague, and companies only need to provide information “in the shortest possible period.”

Hanergy is a warning sign, say critics: evidence that Hong Kong’s regulators are ill-equipped to deal with the new world of opportunity Stock Connect has created. “If you are going to attract lower quality Chinese companies to list, then you have to have the appropriate amount of market oversight,” Philippa Allen, head of Compliance Asia, a consultancy, told Quartz. “You have got to step up corporate governance requirements, and the current system is not achieving that.”

What the regulators should have caught

Hanergy’s fast growth had always attracted skepticism. Questions about whether the company’s bullish projections were accurate were raised as early as 2012 in China’s leading business magazine, Caixin, and followed by well-publicized analyst reports questioning the rich stock price. Still, its shares gained more than 600% in Hong Kong in the 12 months before their May 20 dive. The steepest rise was after the Shanghai-Hong Kong stock connect allowed Chinese mutual funds to invest in Hong Kong stocks in March of this year.

That Hanergy’s share price had skyrocketed despite questions about its business plan was not, on the face of it, a problem Hong Kong regulators should have caught. Hong Kong’s “disclosure-based” regulatory structure assumes that investors do their own due diligence on companies. It also puts the onus on auditors and underwriters to guarantee the information the company provides is correct.

But what the regulator failed to spot, or at least to act on, was highly irregular patterns of trading in the company’s stock. For over two years, “shares consistently surged late in the day, about 10 minutes before the exchange’s close,” the Financial Times reported in March (paywall). Market experts told the FT it was a sign the stock may have been “systematically manipulated.”

And on May 20, the day the company’s stock plummeted, “a wave of erratic computer-driven trades” sank it in less than a second, the Wall Street Journal (paywall) reported. Such a “flash crash,” many experts say, is another example of market manipulation. Hong Kong, unlike some other markets, doesn’t have a “circuit breaker” to automatically stop a stock trading when it falls by a set amount, which is why trading stopped only when Hanergy requested the stock be suspended.

Market manipulation is a criminal activity in Hong Kong that falls under the purview of the city’s market regulator, the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC). A spokesman for Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing (HKEx), the company that runs the stock exchange, said the “statutory regulator will take actions against market manipulation and other inappropriate investor behavior,” and that the exchange did not comment on individual companies. The SFC said it had no comment beyond the public statement that it was investigating.

Another possible sign things were amiss is that Hanergy’s holding company has reportedly taken out billions of dollars in bank loans backed by the company chairman’s shares in the past year. It has been widely reported in mainland Chinese press that the drop happened because banks sold these shares. The company denies these reports, and banks named will not comment on them. What is certain is the parent company has taken out hundreds of millions of dollars in loans from various sources since Hanergy Thin Film’s stock started surging.

According to a HKEx rule passed in 2013, insider information that could be material to the stock price needs to be reported to investors. But these rules, too, allow plenty of wiggle room. As one exchange expert explained to Quartz, a lawyer might argue that no one could have foreseen that these type of loans—if they indeed exist—would be material to the company’s stock price, because in the past the chairman had paid them back.

Hong Kong has outgrown its regulator…

Regulation of Hong Kong’s equity markets, like in many other countries, is a patchwork affair. A committee within HKEx is responsible for examining companies before they list. The SFC is the official securities market regulator. The Hong Kong Monetary Authority supervises banks and the financial markets overall. A police division, the Office of Commercial Crime, investigates stock-market fraud.

Their combined force isn’t enough, critics say. “The government and the regulators just haven’t kept pace with the responsibility they are charged with,” Paul Gillis, co-director of the IMBA program at Peking University, told Quartz.

The total number of companies on the Hong Kong exchange has grown by 43% since 2007, to 1,780, while the number on many rival exchanges has stayed steady or even fallen (2015 figures here are through April). That’s thanks in part to a number of mainland Chinese companies like Hanergy coming to market:

In 2007, mainland Chinese companies accounted for just 30% of Hong Kong’s overall listed companies. By the end of this May, they were about half, and responsible for 72% of the equity market’s turnover.

And the overall market cap of the Hong Kong exchange has reached record highs:

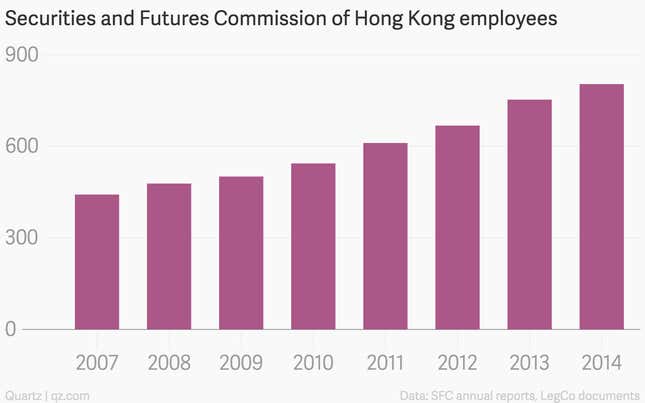

It’s true that the SFC has responded by adding a lot of staff, including budgeting for 50 additional employees this fiscal year (pdf, pg. 2):

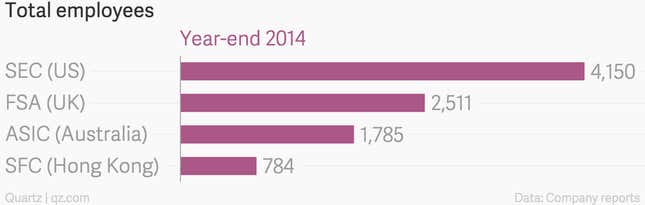

But that still isn’t enough to keep pace, critics say. Although direct comparisons with other markets are impossible—and even the best-regulated markets have blowups—the SFC is minuscule, if judged by staff numbers:

The budget is correspondingly small. Hong Kong’s SFC plans to spend HK$1.67 billion (US$220 million) in the 2014/15 fiscal year (pdf, p. 2). The UK’s Financial Services Authority has £452 million (US$694 million) to play with (pdf, p. 40).

Making things worse for Hong Kong, on June 5, the long-time head of enforcement for the SFC left to join the UK’s market regulator. The SFC is now conducting a global search to find a replacement.

…and merely adding staff won’t fix the problem

Besides the SFC’s small size, there are some structural features that make Hong Kong’s regulation weak. A key part of it, for instance, is the stock exchange’s own Listing Committee, which serves as a filter for which companies should be allowed to list. It has held steady for years at just 28 members, none of whom work full-time for the committee, despite the rise in listings.

As the committee’s latest annual report notes (pdf, p. 26) it has “no staff and no budget.” Of the 28 members, only eight need to “represent the interests of investors.” The rest are made up of “representatives of listed issuers and market practitioners”—lawyers and advisers for companies and brokers trading on the exchange.

A HKEx spokesman told Quartz the Listing Committee “continues to work well in its current form and there are no plans at this time for changes.” He added that the “HKEx is also of the view Hong Kong’s regulatory regime for IPOs has served the city well and continues to be effective.”

Another structural problem—and the reason the SFC has so few regulatory staff—is that the system relies on auditors and issuers, not the SFC, to verify companies’ reported results. But no one is watching the auditors. The International Monetary Fund flagged this problem in a securities regulator review in 2014 (pdf, p. 7):

[T]he current framework does not ensure the independence of the Hong Kong Institute of Certified Public Accountants (HKICPA), which is the body in charge of the supervision of auditors, nor provides it with powers to oversee foreign auditors who audit companies listed in [Hong Kong], nor establishes a strong enforcement framework.

A proposal to add more oversight of Hong Kong’s auditors has languished for a year without a resolution.

Some problems were anticipated before Stock Connect was launched. As the SFC’s chief executive, Ashley Alder, explained (pdf, pg. 6) in a speech last November, mainland investors who want to trade in Hong Kong go through mainland brokers, and Hong Kong doesn’t regulate them:

The fact is that we no longer have a normal situation where we can get client level trading information as we did in the past. In a sense we no longer have a “line of sight” view of what’s going on with the market.

To counter this problem and others, the SFC and mainland China’s market regulator, the China Securities Regulatory Commission, have pledged to share information and cooperate on cracking down on companies.

A market that doesn’t want too much oversight

Hong Kong’s resistance to tough regulation relates in part to the city’s dependence on a handful of wealthy tycoons, critics say. “It’s the nature of Hong Kong society, which is basically an oligarchy or a plutocracy,” Gillis said. “There are many powerful institutions in Hong Kong that will resist any change they find adverse to them.”

“It’s a unique set of circumstances that makes it very different to exchanges elsewhere in the world,” said Allen, the Compliance Asia head. ”There’s no circuit breaker, it’s a very retail-driven share market, there’s a lack of market oversight, and the China market is rapidly opening up and a lot of Chinese companies are seeing the money and saying ‘Yes, I want to list.'”

Without changes, the long-term damage could be severe. “When we had a rash of [Chinese company] frauds in the US, the US-listed China stocks got beat up,” Gillis said. A slew of mainland Chinese stocks that had listed in the US were delisted, suspended or withdrawn in late 2010 and early 2011, after being hit by short sellers and fraud litigation.

“The question is whether the short sellers turn their attention to Hong Kong and find the same problems as they do on the mainland,” Gillis said. “Then, yes, the Hong Kong exchange could lose prestige.”

A riskier, more volatile future

It is not only regulators who are grappling to catch up with China’s fast-moving stocks. Global banks, brokers, and rating agents are scrambling to find educated, bilingual staff who can analyze the mainland Chinese companies rushing to list in Hong Kong.

This dearth of outside analysts means international asset managers, along with mom-and-pop investors, have little information on the mainland Chinese companies they can invest in, or insight into their corporate governance.

The Hong Kong Stock Exchange’s health depends in part on such investors and their faith in the market. International institutional investors contributed 34% of overall trading market share in the 12 months ended Sept. 2014, the largest of any investor type.

But as these investors lose money in stocks like Hanergy Thin Film Power, they could start to lose faith in the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. And that could worsen as Shenzhen’s even riskier stocks come to the market. “At the moment we are only talking about Shanghai,” Allen said. “Once they open Shenzhen [through Stock Connect], which has far bigger corporate governance issues than Shanghai, I don’t know what’s going to happen.”

One worry is that it’s too easy for the shares of many mainland and Hong Kong-listed companies to be manipulated. Hong Kong’s “free-float” rules require that at least 25% of a listed company’s shares not be held by company insiders, and trade freely. But in practice, this 25% is sometimes held by investors who, on paper, aren’t linked to the company—but seem to trade in concert anyway.

Goldin Financial Holdings is another firm that has come under recent scrutiny for wild swings in its share price. In March the SFC issued a “high concentration of shareholding” announcement—one of 11 such announcements it’s made since January this year—about Goldin. It warned that though the company technically met the 25% free float requirement, most of that stock was held by 19 investors, and said investors should “exercise extreme caution” when buying.

A May report by Macquarie Bank described illiquidity in Chinese stocks in general as an often-overlooked market “distortion” that makes them unusual. The average level of free-floating shares in the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges combined is less than 40%, Macquarie said, far below the 65% average in Taiwan, 75% in Japan and 94% in the US.

Already, some investors are betting that mainland Chinese companies—and, by association, their Hong Kong-traded entities—are headed south. On June 4, famed bond investor Bill Gross’s Janus Global fund took to Twitter to declare Chinese stocks traded in Shenzhen the next big short.

Reforms in China and Hong Kong are underway. A slew of new penalties for illegal stock-market trading were announced by the China Securities Regulatory Commission May 22. In Hong Kong, regulators have a number of proposals on the table, including the introduction of circuit breakers and a “responsible investing code.”

But as China’s investors and brokers continue to pour into Hong Kong, no one can tell whether these reforms will be enough. And for the investors holding $21 billion in suspended Hanergy stock, they’re certainly too late.