Traditional auction houses, including Christie’s and Sotheby’s, have quickly embraced nonfungible tokens (NFT), unique digital assets tied to blockchain technology.

When Christie’s sold an NFT of Beeple’s Everydays collage for $69 million in March, it was a watershed moment for digital art, demonstrating broadly that there is a serious market—at least within the crypto community—for prestige art NFTs. These tokens have given digital artists a way to sell cryptographically unique versions of their work to an increasingly welcoming audience.

On Friday (Oct. 1), another historic moment for nonfungible tokens (NFTs) will come when Christie’s auctions off a complete set of Curio Cards, a set of digital collectibles largely considered the first art-related NFTs on the Ethereum blockchain. Ethereum allows the open-source development of decentralized apps and NFTs through smart contracts that dictate the terms of ownership.

Owning a complete set of cards may be extremely lucrative. Noah Davis, who is running the sale for Christie’s, said the auction house’s “conservative” estimate is 250 to 350 ether, or between $750,000 and $1 million. The auction will also be the first called live using the cryptocurrency ether, rather than a fiat currency. Davis said the auction house will begin listing bids in the designated cryptocurrency in an effort to speak the same language as the crypto community.

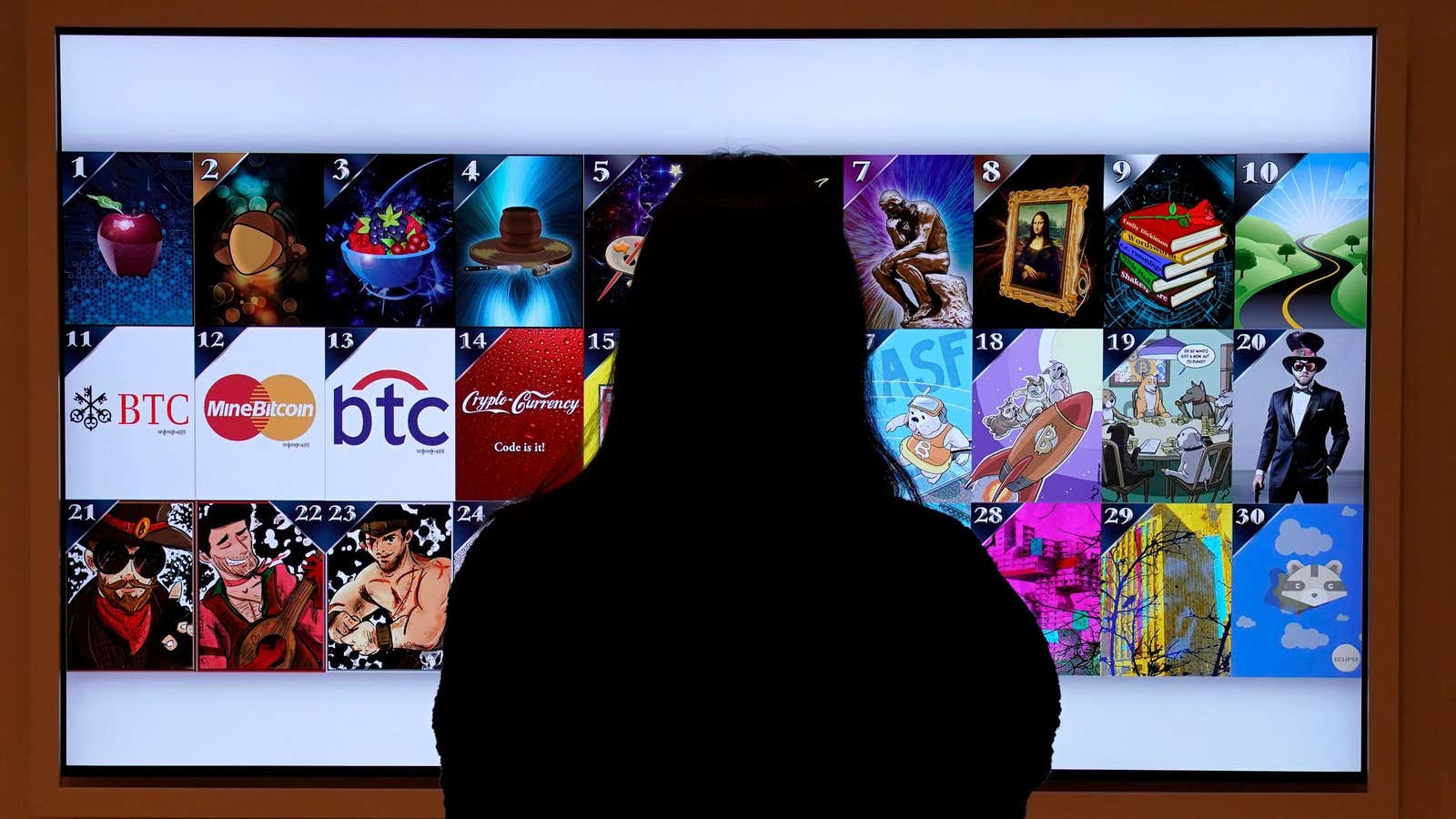

Curio Cards features 30 distinct digital trading cards featuring artwork by seven different artists. Between 111 and 2,000 of each card are currently in circulation. And a complete set, sold at auction by an anonymous seller, even includes 17b, a “misprint,” a series of which were generated by mistake.

The lucrative craze for NFTs could certainly be a flash in the pan, a speculative bubble expanding toward a spectacular bust—or fundamentally change intellectual property online, imbuing trackability and scarcity into virtual goods. Under this vision—tied to concepts of the metaverse, an immersive virtual world that could be the future of the internet—NFTs could provide a model for online ownership that can fuel a new era of the internet economy. If NFTs prove that they are more than just frothy digital assets, then the entire history of these technological gizmos actually does matter. And the relics from its antiquity will be extremely valuable.

But long before Curio Cards could fetch millions of dollars at auction, the project effectively laid dormant for years, adding to today’s appeal. Smart contracts holding the now-lucrative cards were just sitting online. That all changed in March when they were “rediscovered” by a group of NFT “archeologists” trying to piece together a not-so-distant history of NFTs.

An embryonic NFT

Curio Cards was started on May 9, 2017, by co-founders Travis Uhrig, Thomas Hunt, and Rhett Creighton as an online art gallery featuring different digital art trading cards. It started as a business venture, but also as a way to get digital artists paid for their work. Uhrig told Quartz he knew that it could at work as a “Patreon model” for art patrons who wanted to support the digital artists they cared about. The trio enlisted seven digital artists to create the cards and minted tens of thousands of cards with smart contracts on the Ethereum blockchain.

Each artist’s cards are unique. The collection starts with simple objects like an apple, an acorn, a bowl of fruit, a palette, and a stack of books for the first 10 cards. Later, in the series, there are like crypto-themed versions of Wacky Packages, tongue-in-cheek mashups of brand logos with funny slogans. One artist uses cartoon dogs, another turns the co-founders into action heroes, and the last cards in the series are the most avant-garde.

In his lot essay for Christie’s, Davis calls the collection a “convoluted and motley array of surrealist-tinged kitsch, anti-corporate/pro-decentralization satire, slapstick cartoons, high-minded abstraction and hijinks.”

“It’s sort of a car crash in a way,” he said in an interview, “and that’s really charming to me.”

The cards sold modestly, originally for $1 a pop, with all of the proceeds going to the artists. But eventually, the project fizzled. Hunt and Creighton moved on to other projects and Uhrig provided technical support for cardholders but little else. After the initial sale, Curio Cards effectively laid dormant for four years, something of a crypto antique. Meanwhile, the crypto market sank from its peak in 2017 and didn’t surpass its previous heights until the very end of 2020.

Four years after their initial launch, Curio Cards became the subject of fascination.

The archaeologists

Adam McBride calls himself an NFT “archaeologist,” and has built a reputation in a community of like-minded crypto aficionados who genuinely want to understand the origins of NFTs and update them to modern tech standards, something that was necessary for Curio Cards.

Curio Cards are valuable mostly because they are so old. The oldest possible NFT was minted at a conference in 2014 before the Ethereum blockchain even existed. So when NFTs popularity exploded in March 2021, a new generation of crypto enthusiasts began hunting for the oldest tokens around.

McBride was one of them. The NFT boom activated a “treasure-hunter gene,” says McBride, who often spends 18 hours a day on NFT projects enticed by the chance to help resurrect NFT projects. “The idea of having a failed business and then magically four years later it becomes successful is just impossible,” he says. “And it actually happened to these guys.”

Eager buyers found some of the original “vending machines”—early versions of the smart contracts that confer ownership of NFTs—still with active Curio Card contracts in them, though the links on the website had been removed. McBride said he’s since bought and sold Curio Cards, he initially passed up on a group of hundreds of cards that would have been worth about $250,000 today, which he called an “epic and awesome” mistake. He shrugged it off.

What matters to him most, he says, is the connection and community. Right after the rediscovery, he interviewed Curio Cards’ co-founders and artists on his podcast, embedding himself within the community forming around the cards. “The best thing about Curio Cards is I made friends,” he told me, tearing up on our Zoom call. “They’re just really special people, man.”

Bringing Curio Cards to auction

A complete set of cards is now a rare commodity. Uhrig himself collects them, but even he doesn’t have a full set. Only 15 people currently have complete sets of Curio Cards. Because of how rare Card 26 is, there are only 111 possible complete sets. McBride said he helped facilitate the first full-set sale earlier this summer that went for 100 ether, currently equivalent to about $300,000.

Since Curio Cards are so old they don’t work with current technical standards developed for NFTs, Uhrig and other developers built a “wrapper,” essentially a piece of software that fits the original tokens in a modern, transferable token. Even for those who seized on the cards when they were first discovered, they essentially had to wait for the wrapper to be built before they could trade them on peer-to-peer trading platforms like OpenSea.

Updating the cards was necessary given that the most popular NFTs sell for exorbitant prices. CryptoPunks, which debuted just weeks after Curio Cards in 2017, have sold for as much as $11 million at auction. A set of avatars from Bored Ape Yacht Club, a newer project, recently sold for $24.4 million.

While the value increase has made his current work possible, dedicating himself full-time to planning new experiences and integrations around Curio Cards, Uhrig is somewhat uncomfortable with the high price the collection commands. “I like the idea of there being an affordable card…that’s why we did prints instead of individual pieces, so anyone could afford to get one if they wanted,” he said. “So the fact that now the floor is in the thousands of dollars and there’s no twenty-buck or hundred-buck Curio Card is actually a little disappointing to me.”

The emerging metaverse

This tension may be central to the state of art NFTs. They have succeeded in finding ways to get certain digital artists paid for their work—even at high-end auctions like Christie’s. But their value as speculative instruments is likely why many buy in.

NFTs could be central to the internet of the future. In his essay on Christie’s website, Davis lays out a possible vision for the metaverse—an immersive next-generation internet composed of connected virtual worlds—that’s enabled in part by NFTs and other decentralized apps on the Ethereum blockchain. The metaverse, or Web 3.0, has been the buzzword of choice in Silicon Valley in recent months. Speculation is frenzied about who can build the metaverse, what it takes, what standards and protocols will ensure equity, and what role—if any—crypto plays in it.

NFTs could be the way to track ownership of virtual goods in the metaverse. But the high-value nature of NFTs as investment vehicles is in tension with the utilitarian NFTs that could enable future tech. At the moment, speculation seems to be driving the value.

Anil Dash, who created the first NFT with artist Kevin McCoy in 2014, said in an interview with Quartz this May he thinks the current overlap between investors who care about the art and care about the technology is “vanishingly small.” Dash still hopes that NFTs can be a way for digital artists to get paid, but has little faith in its future.

“My most positive interpretation,” he said at a time when NFT markets were down by nearly every metric, “is that it’s returning back to the people who were sincerely interested in it a couple months ago.”