China’s housing market is slumping fast: major developers have slashed prices as much as 15% since March, reports Bloomberg, and housing starts fell 25% in the first quarter of 2014, according to Nomura. Heavily reliant on housing investment, China’s economic growth is swooning. The People’s Bank of China finally took action earlier today, ordering big banks to start churning out more mortgages to homebuyers.

Will more mortgages fix the problem? Analysts are skeptical. Some note that boosting mortgages won’t necessarily stoke demand, meaning the government will need to relax credit policies further. Plus, by shoring up prices, looser credit might cure a symptom, but it also risks spreading the underlying disease: an overwhelming glut of supply that has infected not just the property market, but much of China’s economy.

Why cheaper real estate isn’t always an incentive to buy

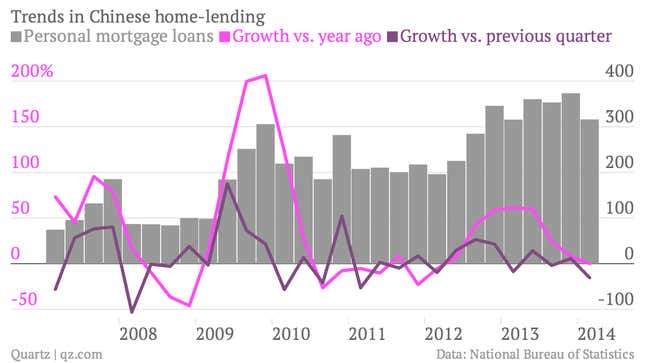

In theory, loosening mortgages is the right idea. Mortgages were down 15% in the first quarter, compared with the last quarter of 2013. This is happening, says China Confidential’s Rafael Halpin, because tighter credit is pushing first-time buyers—meaning those who actually need homes and aren’t just investing to make money—out of the market.

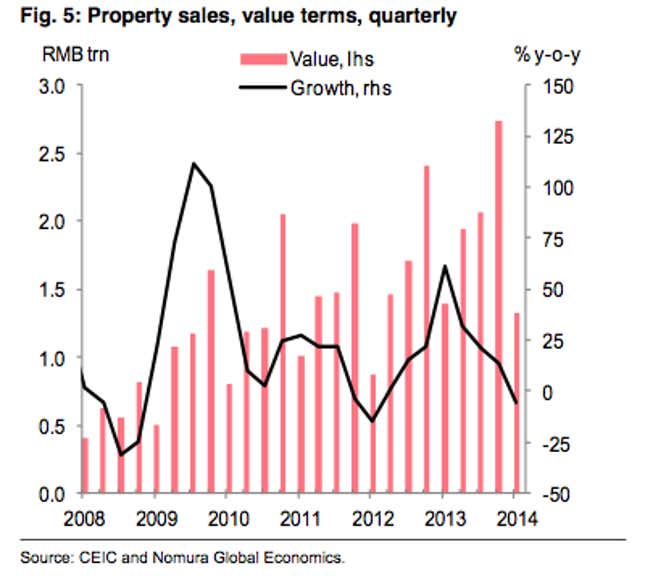

That tightening of credit has contributed to plummeting sales: The value of homes sold dropped 5.2% in Q1, versus the same quarter in 2013, while the actual number of units sold fell 3.8%, reports Nomura:

The problem is that once prices start falling, potential homebuyers get skittish about a further drop. And with good reason: downpayments and mortgages generate around 40% of developers’ investment capital. Slumping sales means developers need cash so desperately that they’ll cut prices to the bone.

David Cui, a strategist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, described a psychology that has “gone sour,” with cheap prices doing little to goose demand: “Given the over-supply situation and developers’ balance sheet pressure, it’s most likely that developers will keep cutting prices,” Cui wrote in a note this morning. “This, ironically, will probably make more potential buyers [remain] on the sideline, including genuine-demand home buyers.”

Widespread knowledge of property developers’ shaky financial states is exacerbating the problem, and making buyers particularly skittish about investing in unfinished developments (when developers are especially desperate for cash).

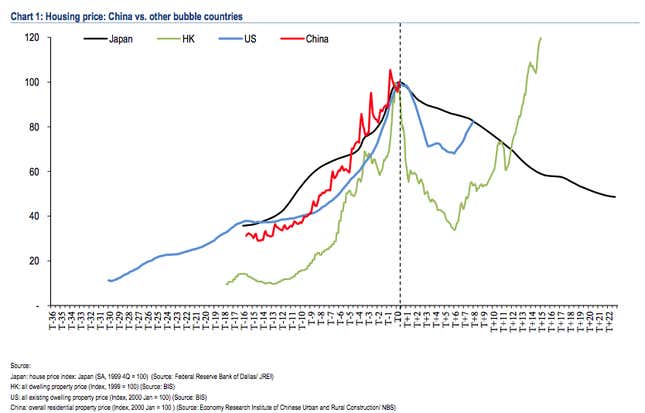

“Pre-sales are being doubly hit by the fact that buyers are worried about a developer going bankrupt before completing the project, and [are] preferring to buy completed units,” explains China Confidential’s Halpin. That’s certainly what happened after the prices started falling in other markets:

A competing theory: withering demand

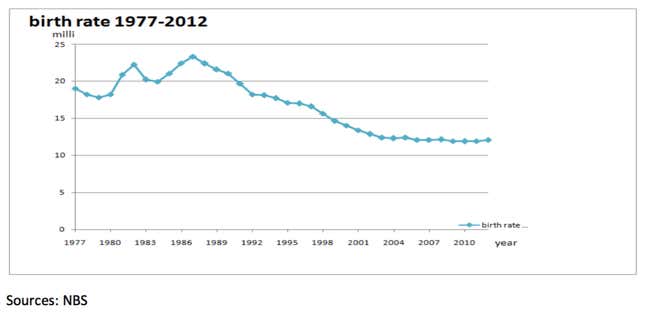

While Halpin and others argue that the rising cost of borrowing is driving out first-time borrowers, others attribute falling demand to China’s demographic tipping point. The research firm JL Warren Capital recently made the case that the upshot of China’s one-child policy is a birth rate that peaked in 1987, meaning that there are simply too few twenty-something couples forming families to buy the existing supply of new homes.

As for the drop in mortgage lending, BofA/Merrill Lynch’s Cui notes that banks make much tidier profits from selling products tied to shadow lending—high-yielding off-balance-sheet investment products—than they do mortgage loans.

The one way to prevent a huge hit to China’s GDP: more credit

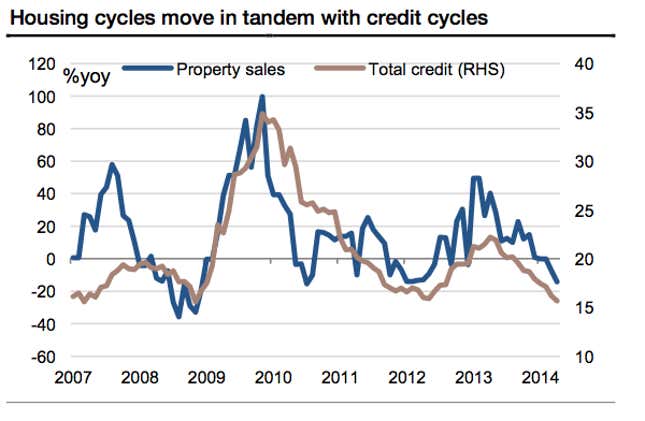

Regardless of the cause, though, China’s housing implosion is threatening to drag down its GDP. China’s housing sector is unusually central to its economy, accounting for at least 20% of total output once you factor in related sectors, says Société Générale economist Wei Yao. The problem is that, as in many countries, China’s housing boom has been driven by excessive lending. The Chinese government clearly knows this: as you can see in the chart below, every time property sales started dropping, the government eased credit controls.

Credit transmission is broken

That’s exactly what those pointing to the Chinese government’s “room to loosen” are hoping for—that it will slash the reserve requirement ratio (RRR), the capital the banks must provision against losses, or lower benchmark rates. However, there’s already a lot of credit in the system. In fact, counting off-balance-sheet lending, credit was growing four times faster than GDP on a 12-month rolling basis, says Victor Shih, a professor at University of California-San Diego.

No, the problem isn’t the amount of credit, but that it isn’t going to the right places. The most debt-saddled sectors are state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and local governments, which invest in real estate through local government financing vehicles (LGFVs). The sectors that tend to be dominated by SOEs are cement, steel and other industries saddled with overcapacity.

Take cement, for example. In the last decade, China has invested so heavily in cement factories that it now has more cement capacity than the rest of the world combined, according to The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Robert Ward. In 2011 and 2012 alone, China churned out more cement than the US did in the entire 20th century (paywall). You can bet that all those cement companies aren’t making money now; what’s keeping them afloat is fresh bank credit and property investment.

What will happen to them as property investment peters out? Loosening credit could offset that. But that will mean banks will pump even more credit to sectors that are already producing too much to begin with, siphoning much-needed credit away from non-state companies that desperately need capital. Plus, opening the credit floodgates will likely drive property prices even higher than they had been.

Reforms are trickier than they seem

Fully aware that credit isn’t going where it’s needed, the government has a plan to fix the problem: letting the market set interest rates. It will achieve this via complicated reforms its leaders proposed in November 2013.

Why hasn’t the government made much progress? These policies require seismic shifts in the structure of China’s economy. Lifting government control on deposit rates means that banks will have to compete with each other for both household savings, raising interest rates across the board, and for loan business, encouraging a lending binge as banks struggle to boost their profits. Since China’s economy is running on credit right now, liberalizing interest rates risks worsening its already scary debt problems—which means that option is pretty much off the table for now. Another option, letting SOEs fail, is unlikely, due to the powerful interests entangled in those companies.

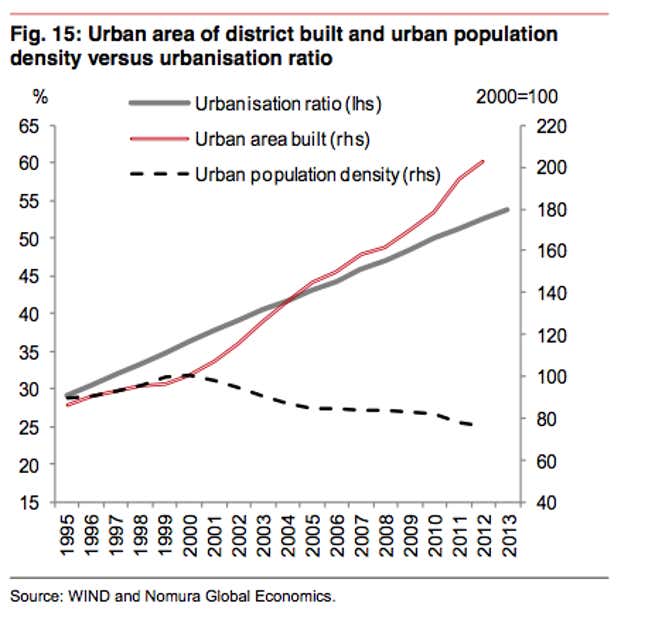

Some expect that reforms designed to spur ”urbanization,” championed in particular by premier Li Keqiang, could stimulate demand as migration to new urban areas juices construction. However, China Confidential’s Halpin says that markets in smaller cities have already expanded rapidly to accommodate the urbanization push. So while that that new construction might find buyers in the long run, “the danger is that that stock is dumped before these reforms play out.”

Others are even warier. Zhang Zhiwei of Nomura argues that urbanization might be more trouble than it’s worth. “The government-driven urbanization model has meant prosperity for local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) and property developers, but has crowded out other industries’ access to resources,” he wrote in a recent note.

Financial sector: where the shadows lie

China’s banks are already deeply intertwined with the property sector. Loans to the property sector make up at least one-fifth of all outstanding loans, up from 14% in 2005. The growth of shadow lending—as off-balance-sheet credit is known—has risen rapidly as well.

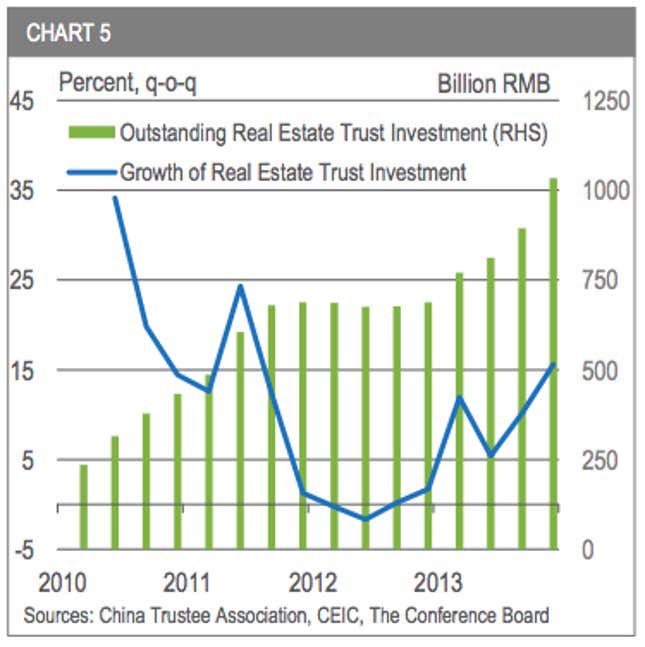

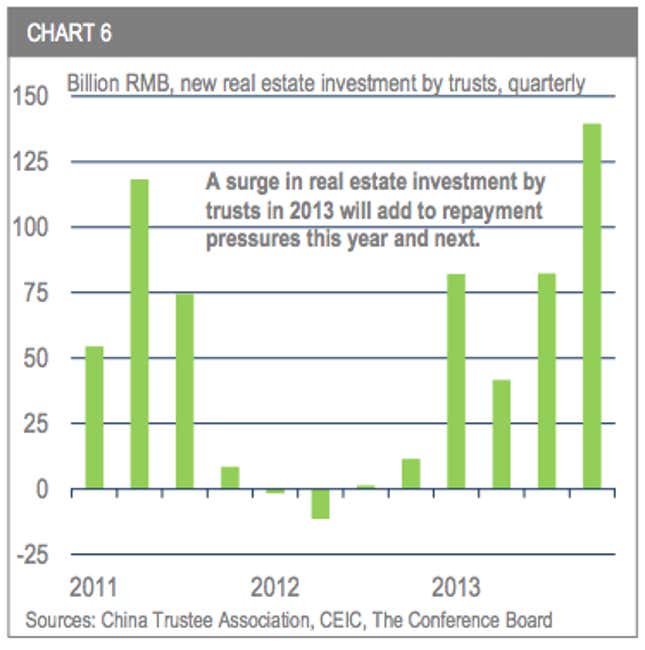

But huge risks to the entire financial system are gathering in these shadowy sectors. Take for example trust companies (firms that are allowed to invest in assets but can’t accept deposits): At the end of 2013, trust loans to real estate companies totaled 1 trillion yuan ($160 billion), up 45% on the previous year, according to Andrew Polk, a China economist at The Conference Board.

“These types of loans hold particular risk because they are the most likely candidates for spreading contagion throughout the financial system,” says Polk. “Real estate is widely used as collateral for obtaining both bank and non-bank credit, so any sustained fall in prices could potentially tip into a downward spiral” of falling prices, as defaults prompt trust companies to sell off that collateral to pay investors, driving prices down further.

And since trusts don’t set aside capital to protect against defaults, either households that bought the product in the first place will have to swallow losses or the banks that marketed them will. The test of who foots the bill will come this year; the surge in trust lending to real estate in 2013 means that some 450 billion yuan of those investments will come due in 2014 alone, says Polk.

China’s policy tightrope

Today’s directive on mortgage policy is the first big step by China’s leaders to address the massive challenge they face: easing credit just enough to buoy the economy and boost confidence, but not so much that it adds to the already dangerous pile of debt, driving more good companies out of business while propping up developers and state-owned industrial companies. SocGen’s Yao says this balancing act will be tough to carry off. ”It is possible,” she says, “but the margin for error is big.”