The Chinese government’s censorship has effectively erased most politically sensitive issues from both the country’s internet and daily conversations. But this has also led to inadvertent breaches of taboo topics by many Chinese youngsters, including the country’s top influencer Li Jiaqi.

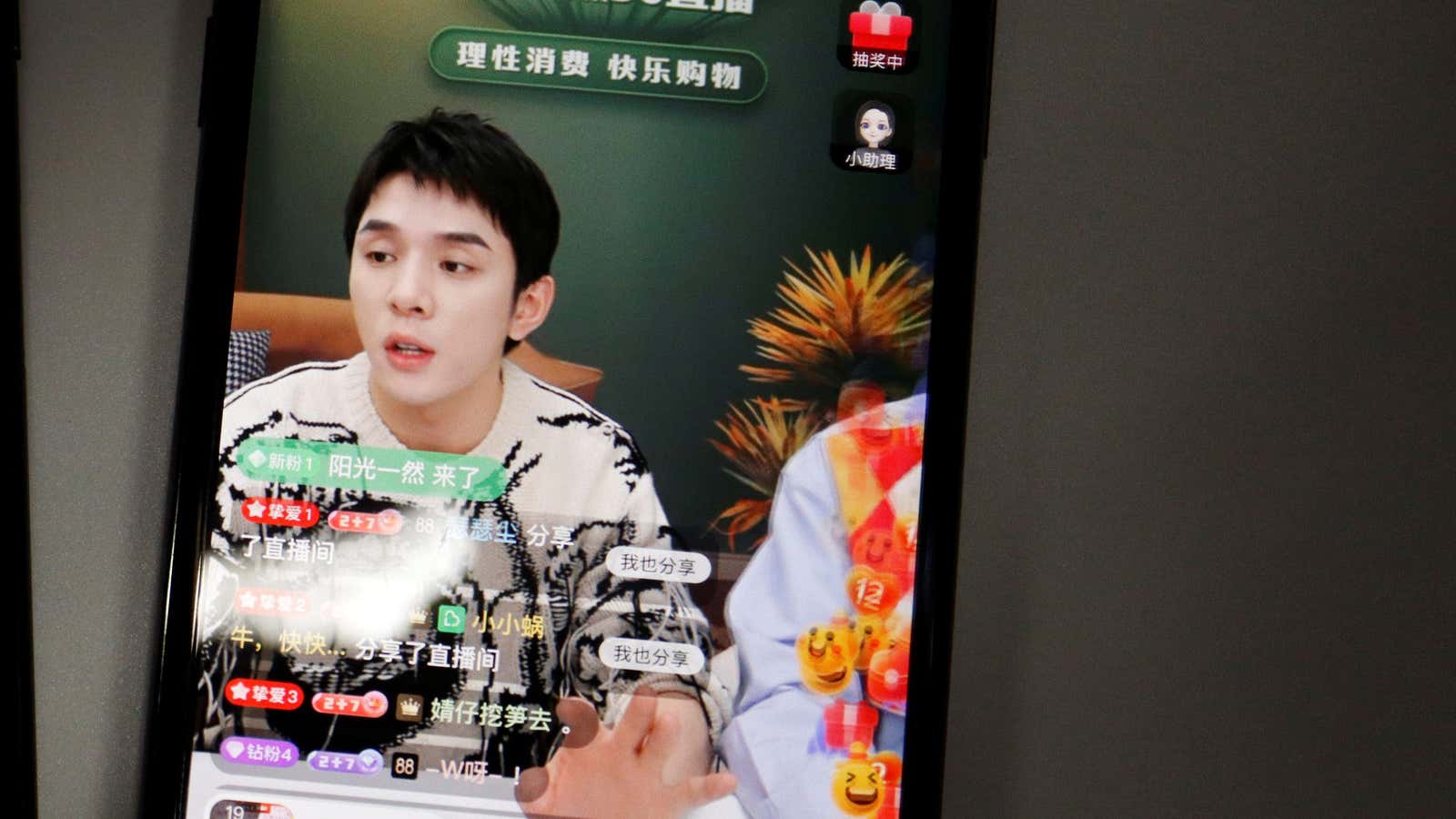

Dubbed by some as the “lipstick king” for his amazing ability to promote cosmetics, 29-year-old Li is China’s top live e-commerce influencer who once sold $1.7 billion worth of goods in 12 hours. Li currently has over 64 million followers on the Chinese e-commerce platform Taobao, and viewers of a single session of his livestream can reach tens of millions.

But just as Li’s career was gaining momentum, partly because his major rival Viya disappeared from the industry for tax evasion last year, a seemingly innocuous move during one of his livestreams last Friday (June 3) has become the biggest crisis he has ever faced. During the session, Li and a co-host displayed a layered ice cream flanked by round cookies and topped with black stick that appeared to be made of chocolate, all of which made the dessert look like a tank, according to the Wall Street Journal. Almost immediately after Li presented the ice cream, his livestream was suspended, said the outlet.

The episode showcases the heightened risks for business figures in China, where political redlines are becoming almost impossible to keep track of. In Li’s case, the timing of the appearance of the tank-shaped dessert is the main problem. On June 4th, 1989, the government ordered the military to quell student protests in Beijing. A video showing an unidentified man facing down a line of tanks in Tiananmen Square made images of tanks into a symbol for supporters of the students.

The quick suspension of Li’s livestream, ironically, is leading Li’s many young followers to try to figure out what happened on June 4th, which is usually mentioned only as a political turmoil in Chinese textbooks. Many wrote on Weibo that they asked their parents about the incident, while others say they used “blue bird,” a reference to Twitter, to learn about it. “This is so off, on one hand [the government] doesn’t allow people to know about historical events, on the other, they punish those for not knowing about them,” said a Weibo user on Li’s account page.

It is unclear whether the suspension of Li’s livestream was a decision by his company or an order from the Chinese authorities. On Friday, Li said on Weibo that the suspension was due to a technical problem, and he promised to bring more good merchandise in future sessions. But a livestream event he scheduled for Sunday also did not air, without explanation. So far, Li’s account on Weibo is still visible, which many take as a sign of his safety since previously public figures who have drawn the ire of the government, including Viya, had their social media accounts erased quickly. The stakes are high for Li, who has been preparing for a major Chinese shopping festival this month. If he has to be absent from the festival, the losses for him and his e-commerce platforms could be huge.