Roku, the streaming hardware company, began its life in 2007 as “Project Griffin,” a Netflix initiative to make streaming easier. Netflix decided at the last minute to spin the project into its own company and Roku went public in 2017.

But Roku employees are now speculating their former parent company might become their new one. Roku recently disallowed employees from trading its shares, according to a report from Insider, a move that signals the possibility of an impending acquisition. Roku staff reportedly see Netflix as the most likely candidate.

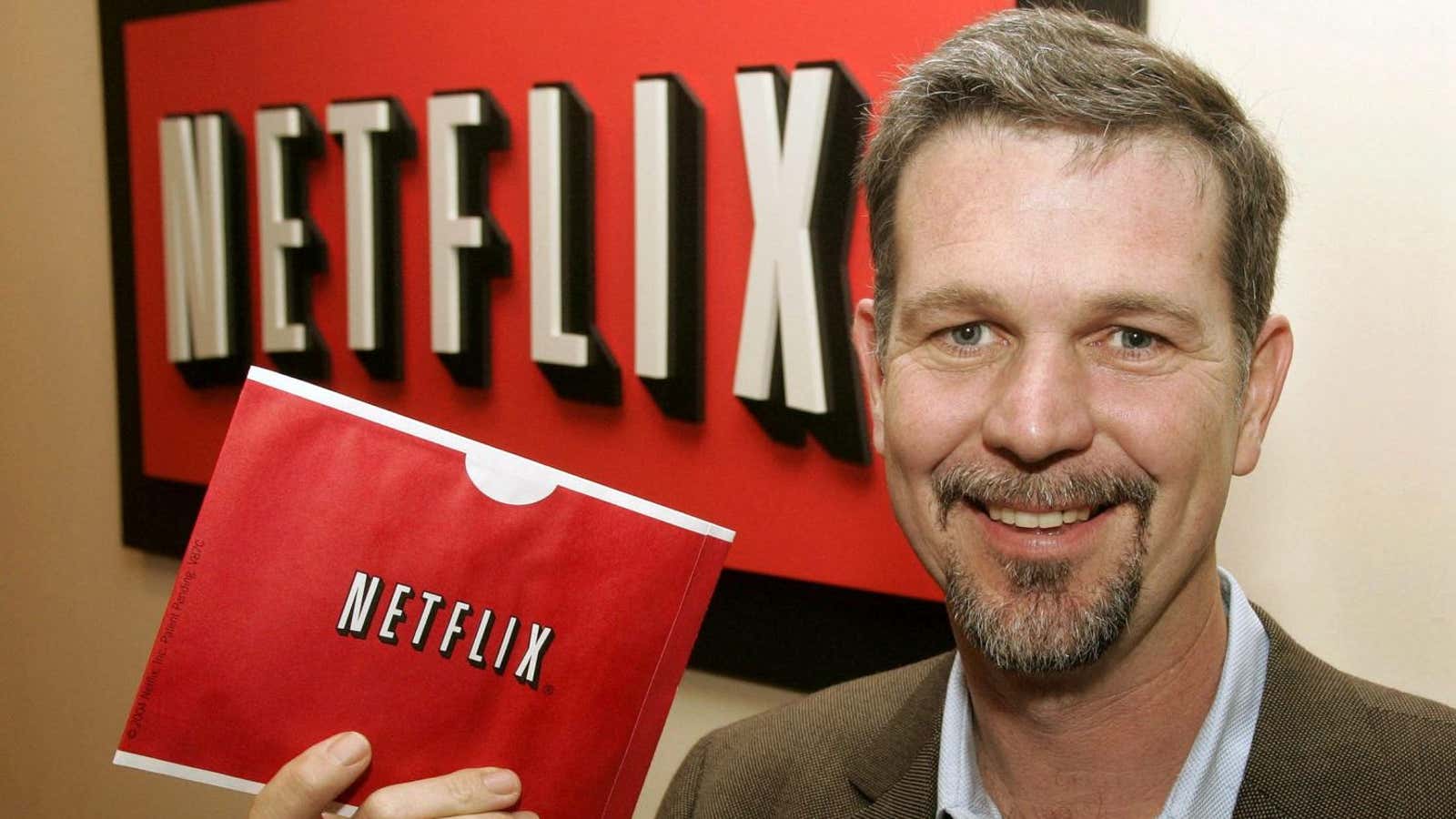

The potential deal says a lot about how streaming has changed in the past 15 years. Netflix CEO Reed Hastings originally decided not to launch the device that became Roku because he worried it would hurt his ability to partner with companies like Apple. At the time that made sense: Streaming was nascent, Netflix was still mostly a DVD-by-mail service, and its ambition was to be the best high-end content library with the best recommendations. Getting into hardware might rouse giants in tech and cable.

But the giants were roused eventually. As I wrote in April:

Every company that defines a new business model goes through two phases. First it fights to grow the market, then it fights to defend it. In its first two decades, Netflix taught customers a completely different way of watching TV and movies: more binging, more browsing, and no ads, all at a monthly price well below cable. It grew alongside a global expansion in internet access, and in people willing to “cut the cord” with cable. But imitation is both the sincerest form of flattery and the sign of a healthy market. Netflix showed the world how valuable the digital subscriptions business can be, and the world piled in after it. Today the streaming giant sees competition in Amazon, Apple, Disney, Hulu, and HBO, and in other subscription businesses it helped usher in, such as Spotify, the New York Times, and Peloton.

Gone are the days when Hastings could say with a straight face that Netflix didn’t compete with companies like Apple and Amazon. And, putting aside the price tag, an acquisition of Roku would make a lot of strategic sense.

Roku has an advertising business

Perhaps the most compelling reason for Netflix to buy Roku is that the latter already has an advertising business, which brings in more revenue than its hardware sales. Netflix, which has long avoided ads, has softened its position and badly needs to expand in that direction. A Roku acquisition would provide a team and even more audience to sell against.

The point of aggregation has changed

A Roku acquisition could also improve Netflix’s competitive position, which has changed as the industry has matured.

Here’s a bit of strategy 101: The most profitable businesses have lots of potential suppliers, lots of potential customers, and very few direct substitutes. There’s competition at every spot in the “value chain” except for where they sit. That’s why internet platforms are so valuable—Google, Amazon, Airbnb, and Uber all match tons of buyers with tons of sellers and they get better as they get bigger so it’s difficult for other companies to match them.

For its first decade or so in streaming, Netflix had this sort of advantage. There weren’t many other alternatives and content makers were willing to license their libraries. Today, Netflix faces a much more competitive market. There are other libraries to choose from and Netflix has to pay more to license content or to make it itself.

By buying Roku, Netflix could move up the value chain and own an app that is a library of other apps. Roku has competitors too, including Apple, Amazon, and Google. But between its hardware and its partnerships with TV manufacturers it holds a strong position that Netflix lacks: it controls the home screen for lots of streamers. With more and more streaming apps to choose from, the home screen is becoming more valuable. It’d be a bit like going from being Facebook to being Apple: Netflix would control a major operating system that customers use to stream.

The Netflix recommendation engine could make Roku better

Netflix has long staked its reputation on its algorithmic prowess. It promised users not just a good library but good recommendations of what to watch. That’s waned a bit as it has relied more on original content; the company has a strong incentive to promote Squid Games to as many of its users as it can, not just the ones whose tastes perfectly align.

But buying Roku would create new opportunities for Netflix to make recommendations. The first thing Roku users see when they turn on the TV is the Roku home screen. Netflix could help Roku add recommendations to that screen, combining its extensive dataset on users’ viewing with Roku’s data on what users search for.

This combination would get Netflix back to recommending across the entirety of what someone watches, closer to how it worked in the early days. Searching for Slow Horses on Roku? That’s an Apple TV show, but if Netflix owned Roku it could leverage that data to recommend spy thrillers in its library.

Streaming isn’t just about TV and movies

Here’s how I concluded my April piece on streaming subscriptions:

In this world of subscription fatigue, the race is on to become the one consumers won’t dare cut. When that meant having the best video library and streaming app, Netflix was positioned to win. Now it means bundling different subscriptions together, as Amazon Prime does with video and delivery, and Apple does with TV, music, fitness, and cloud storage.

My colleague Tiffany Ap made the same case in her argument that Netflix should buy Peloton. Roku is more expensive than Peloton, but it’s a safer step towards Netflix becoming a super app. Peloton has a Roku app; so do Spotify and Twitch. By owning the hardware, Netflix would become the window into a wider range of streaming services—including fitness, music, and games—and would collect valuable data on how users interact with them.

There are factors that argue against an acquisition, too. A lot depends on the price, for one. And the deal could trigger antitrust scrutiny from US regulators who’ve made it clear that they are more concerned about vertical mergers than past administrations. Finally, big acquisitions just often don’t work out. Netflix might decide its ad business would be stronger if built from the ground up to suit its needs. They could even decide it’s cheaper to just build their own streaming hardware. After all, they’ve done it before.