Yields on Spanish government bonds have plummeted over the last year, as prices for the bonds have rallied. (Yields—the rate the market charges a country to borrow—move in the opposite direction from prices.) Today, that rally hit another significant milestone as yields on Spanish government bonds—just a few years ago seen as one of the riskiest assets in the financial world—fell below the yield on the US 10-year Treasury note, one of the financial world’s benchmarks of safety.

ECB chief Mario Draghi set off the relentless move lower in Spanish bond yields back in July 2012, when he promised to do “whatever it takes” to ensure the survival of the European common currency. You can see the impact of that handful of words in the chart below:

So does that mean that for all intents and purposes the bond market thinks that Spanish debt is just as a safe as the full faith and credit of the US government? Not exactly.

It’s always tricky to compare bond yields across countries and currencies. For one thing, yields go up and down for a lot of reasons. Sometimes, when they rise, it means people think the chances of default are higher. At other times it might just mean that expectations for economic growth are picking up and there are better things to own than super-safe government bonds.

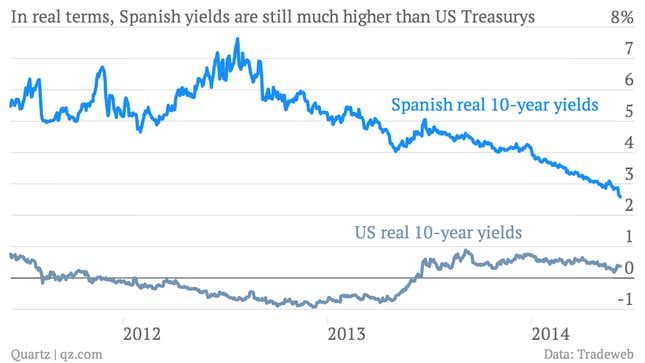

But there are also important differences in currencies and rates of inflation and economic growth that should be taken into account. For instance, the chart above shows the nominal yield on 10-year government bonds. But you can also look at so called “real yields”—the yields on the inflation-indexed government bonds of both countries. Real yields tell investors the market’s best guess for how much money will be left over on an investment after inflation has eaten into those fixed returns.

You can see that Spanish “real” yields are still far above “real” US yields. So what does that mean? Well, basically, that a lot of the decline in Spanish bond yields over the last year reflects not just the ECB’s guarantee, but also the prospect for very low levels of inflation, or possibly even deflation, which isn’t a good sign for the Spanish economy.

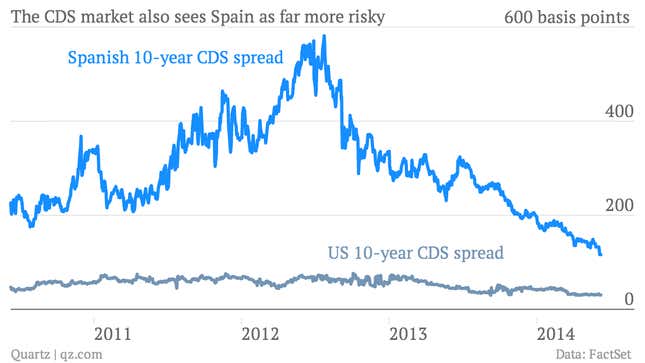

Other measures of risk, such as the cost (“spread”) of credit default swaps (a type of insurance against defaults on government debt), also suggest that the market still sees Spanish government bonds as much more risky than the US.

So investors still consider Spain’s government bonds to be far more risky than the US’s. On the other hand, they’re a lot less risky than they used to be just a year ago.

And by the way, that’s a very good thing. High yields on national government bonds mean higher costs for consumers and businesses to borrow in those countries—part of the reason European banking system hasn’t been doing much to help Europe’s economy grow.