It’s generally wise to ignore any instructions that come via unsolicited emails, texts, and Facebook messages. But when thousands of Bulgarians recently received mysterious missives warning them that local banks were in trouble, they were spooked enough to line up at branches and withdraw their savings. Before long, the sight of these lengthening queues—and more breathless messages—encouraged others to take out their deposits, just in case the rumors proved true. This is how a bank run begins.

Today Bulgaria established an emergency credit line worth 3.3 billion levs ($2.3 billion) to backstop the two lenders under attack. Fibank and Corpbank are the country’s third- and fourth-largest banks, respectively—Corpbank was taken over by the central bank a few days ago and Fibank was forced to close early at the end of the week as it struggled to cope when some 800 million levs were withdrawn in a single day.

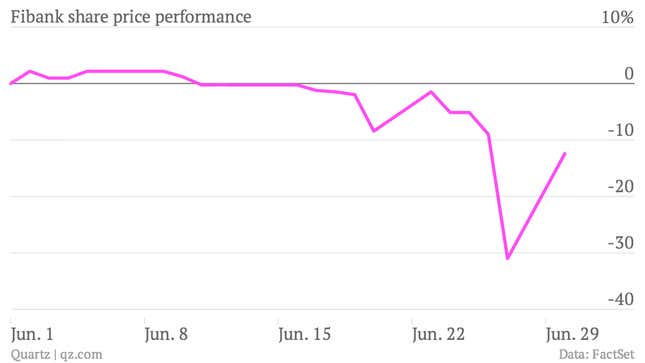

The frenzy appeared to die down somewhat today, although savers remain on edge. Fibank’s shares, which tumbled at the end of last week, regained much—but not all—of their lost ground:

Bulgaria’s central bank said the runs were driven by ”an outbreak of rumors and malicious public statements,” and several arrests have been made in connection with the supposed plot. As far as anyone can tell, the turmoil appears to stem from a spat between the businessman Tzvetan Vassilev, chairman of Corpbank, and the parliamentarian Delyan Peevski. The one-time business partners reportedly fell out over control of the country’s former tobacco monopoly, a variety of unpaid debts, and abrupt corporate account closures at Vassilev’s bank, which was the first to see a run on deposits. Oh, and each has also accused the other of plotting his assassination.

The theory goes that shadowy forces are taking advantage of the turmoil to destabilize the banking system and force officials to break the lev’s rigid peg to the euro, put in place after a brutal banking crisis in 1996-97 led to a bout of hyperinflation. Or, at least, that’s how Vassilev’s theory goes—as he told the Financial Times (paywall), “I suspect the involvement of political figures and businessmen with huge debts they want to melt away.”

The financial upheaval comes amid political instability—the two are rarely far apart in Bulgaria—as popular discontent has forced the current government to call for early elections for October after just over a year in power. A caretaker government will assume power ahead of the poll. When the credit rating agency Standard and Poor’s downgraded Bulgaria’s government bonds earlier this month, the country’s dysfunctional politics were the main point of worry, particularly the inability of officials to temper “rampant graft,” according to Reuters.

It could be worse: Although Bulgaria is both the EU’s poorest and one of its most corrupt member states (pdf), its relatively small banking system is well capitalized and public debt is relatively low. The government managed to sell a 10-year euro-denominated bond last week at an interest rate of just over 3%, despite the burgeoning banking turmoil. Like other EU states, deposits up to €100,000 ($134,000) are guaranteed whatever happens to the bank where they are held.

This evening Bulgaria’s central bank issued a series of measures: easing liquidity requirements, proposing automatic jail sentences for spreading false information about banks, and declaring that the country’s banking system “has returned to its normal functioning.” Even if the crisis was largely manufactured—given its murky origins, it could be some time before we know all the details—the episode demonstrated the shallowness of Bulgarians’ trust their banks.

Boiko Borisov, a former prime minister whose party is leading in the polls, says he wants to call in the International Monetary Fund to help the country—not necessarily for extra funds, which Bulgaria has proved it can raise on its own or with the help of the EU, but “mostly for expertise so that the country can calm down,” he says. Indeed, if all it takes is a few anonymous text messages for savers to drain their accounts in haste, this country seems to have a case of the jitters.