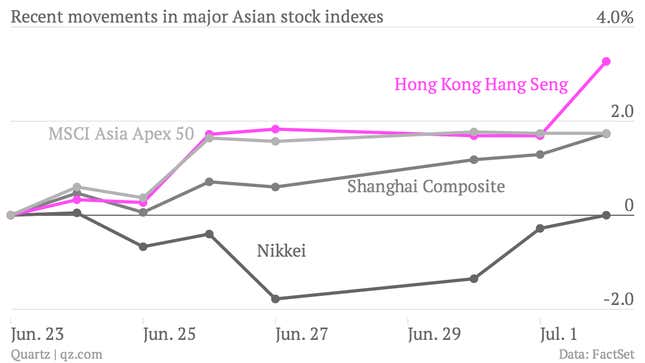

Markets typically dislike mass protests; they portend instability. But though nearly 100,000 Hong Kong residents (according to police; half a million according to the organizers) thronged the streets of the island territory to call for electoral reform yesterday, the stock market—which was closed on July 1 because it was a local holiday—reacted with aplomb today:

The Hang Seng index’s 1.6% pop—bringing it to 23,549.62—was the biggest increase since early May. And this wasn’t just an Asia-wide thing, as you can see:

That might have something to do with the solid data on China’s manufacturing sector released late yesterday, as well as the government’s recent stimulus efforts.

Then again, among the Hang Seng’s sub-indexes, the Hang Seng HK 35 bounced the most, gaining 2.2%. This index is made up of the 35 biggest Hong Kong-listed companies that mainly don’t do business with mainland China, including companies like Swire, Cathay Pacific and Li Ka-Shing’s Hutchison. By comparison, the Hang Seng China 50 index, which tracks the largest Chinese companies listed in Hong Kong, was up only 0.9%.

Why, if the economic data out of China look promising, would Hong Kong-focused companies outperform mainland firms? Probably, says the New York Times (paywall), because the business world was simply relieved that the July 1 demonstrations and overnight sit-ins were peaceful.

Unrest had clearly been a concern. On June 27, the “Big Four” global accounting firms—Ernst & Young, KPMG, Deloitte and PwC—published a joint statement in three Hong Kong newspapers saying they opposed the territory’s democracy movement (paywall). Street protests could disrupt the stock exchange, banks and financial services, causing “inestimable losses in the economy” and prompting multinational clients to leave Hong Kong, argued the ads. The campaign was apparently initiated by the Hong Kong branches; the headquarters of the Big Four firms told the Financial Times (paywall) that they had only heard about the ads through the media. (We’ve contacted the Big Four for comment; we’ll update if we hear back from them.)

However, many suspect that the accounting firms weren’t all that worried about business disruption, but were submitting to pressure from their government-owned clients on the Chinese mainland. Earlier in June it came out that two banks, HSBC and Standard Chartered, had severed long-standing advertising relationships (paywall) with the Apple Daily, one of Hong Kong’s leading independent newspapers, after the Chinese government instructed them to do so.

Some are skeptical about the long-term wisdom of cozying up to Beijing. “The arrogance of the firms is stunning,” said Paul Gillis, an accounting professor at Peking University, one of those who think the Big Four ads were in response to government pressure. “Taking a controversial stand on a political issue is bound to alienate many clients, partners, and staff. Is it really worth destroying trust to gain a few political points with certain elite clients?”