Russian stocks and bonds are dropping today, as is the ruble. It is difficult to isolate a single factor in the fall, as the threat of tougher US and European sanctions, a stagnating economy, and each new twist in the crisis in Ukraine conspire to weigh on Russian assets.

Today, though, a big factor in the slide is undoubtedly the ruling by an international arbitration court in The Hague, which found Russia liable for a whopping $50 billion in damages for former shareholders of the oil company Yukos. The company was seized by the state in 2004 in a “devious and calculated expropriation,” the court said, with its boss, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, spending a decade in prison.

Rosneft, now the world’s largest listed oil group, picked up most of Yukos’s assets via auction after the firm was forced into bankruptcy by crushing back-tax claims. Rosneft and its chairman, Igor Sechin, were both recently targeted by US financial sanctions.

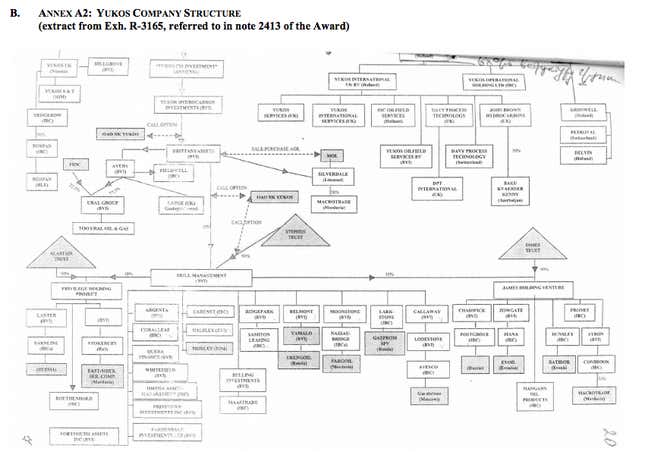

Although $50 billion is undoubtedly a lot of money, it’s a drop in the bucket in terms of Russia’s reserves. But Russia is likely to appeal to decision, which is based on an international energy treaty that the Kremlin once signed but later rejected. The court’s 615-page ruling (pdf) sets out the evidence for the direct responsibility of the state in the downfall of Yukos and determines appropriate damages for ex-shareholders in the mind-bendingly complex company:

The Yukos ruling, in theory, puts a wide range Russian government-owned assets around the world at risk of seizure—more than 100 countries are members of the arbitration court in The Hague. But recovering damages could be a challenge. One of the only successfully enforced arbitration awards against Russia—$2.35 million awarded to a German businessman in 1998—has recovered only part of the damages to date. A Russian government-owned building in Sweden was seized in connection with the case, and some Russian ships have steered clear of the country since, fearing a similar fate. This echoes the recent detention of an Argentine naval ship by a hedge fund seeking to enforce compensation for defaulted debt.

Amid the tense stand-off between Russia and the West over the unrest in Ukraine, the timing of the Yukos ruling is terrible for Moscow. But since the case was first brought in 2005, it seems unrelated to the current tensions. (Unlike, say, the British government’s reopening of a long-dormant murder case that implicates the Kremlin.)

Whatever the case, the Yukos ruling is yet another blow to Russia’s reputation among international investors. The country’s central bank unexpectedly hiked interest rates last week, fighting rising inflation at the expense of weak economic growth. Big money managers say they are taking a “fundamental reassessment” of their exposure to Russian securities with sanctions looming.

Whether the pressure on Russian assets has any effect on Vladimir Putin’s policies remains to be seen, but it’s increasingly clear that the country is becoming a pariah among international investors.