Like guns, country music, or the convoluted healthcare system, the brutal sport of American football—and the sheer, unbridled passion for it—is one of those things that non-Americans can find difficult to comprehend. While baseball has a strong foothold in Asia and Latin America and basketball is now genuinely global, the US’s favorite homegrown sport is the one that has translated the least abroad.

But the most interesting thing about football, hard to appreciate from afar, is that to this day, much of its popularity comes not from the professional National Football League (NFL)—currently embroiled in a couple of its own scandals—but from amateur games played by university students.

The NFL is easily America’s biggest, richest and most popular sporting league of any kind. And the college version from which it was spawned is not that far behind. College football is the third most popular sport in the US, only just behind Major League Baseball, according to widely followed surveys, remarkable given baseball’s status as the national pastime. It is also a huge business. While complete data aren’t publicly available, just the 123 teams in the Football Bowl Subdivision (the uppermost echelon of college sports) reported $3.2 billion in revenue in the last fiscal year. The NFL’s annual revenue is about $10 billion.

And college football, or more accurately the whole subculture around it, explains America better than any other sport.

It’s intimately tied up with American history

America’s version of football was born in some of its oldest colleges. The first game, which probably more closely resembled soccer, was between Princeton and Rutgers in 1869. In the ensuing decades, as tertiary education attendance boomed (pdf, page 65), increasing nearly fivefold between 1899 and 1930, it spread from elite, private, east coast colleges into big, public universities, particularly in what are known these days as “red” (Republican) states of the midwest and south.

Until the 1950s, it arguably was more popular in terms of audiences than its professional cousin. Today, outside the biggest cities, and in areas where the NFL is absent (including “blue” parts of the country like Los Angeles and Oregon) it has a strong following. In large swathes of the south and midwest, even in some places where the NFL juggernaut is present, college football reigns supreme.

The sport also has been closely tied to key historical events. President Richard Nixon used college football to entrench his appeal below the Mason-Dixon line, as part of a so called “southern strategy” that helped capture what was historically a Democratic stronghold for the Republicans. Black college football teams played a role in the civil rights struggle. Even earlier than that, president Teddy Roosevelt, a great reformer of Wall Street and corporate America, also reformed college football, convening a summit in 1905 to make the game less violent and dangerous. And today, as economists debate rising inequality and low minimum wages, college football debates whether student athletes—who aren’t paid, but get scholarships—should be compensated more.

Michael Weinreb, the author of the new book Season of Saturdays: A History of College Football in 14 Games, explains that the fervent support for college football stems from one of the most powerful marketing tools there is: nostalgia. “It appeals to people’s nostalgia, because they either went to school there or they grew up there, and they think they can get back to that place,” he tells Quartz.

Yet fans aren’t always students and alumni. Notre Dame University’s team, for example, historically had a large following among the Irish-American communities in places like New York City, miles away from the actual university in Indiana, he says. It’s a similar story in the south. “Half the people in that stadium can’t spell LSU,” James Carville, a Louisiana State University alumnus and former adviser to Bill Clinton, told the Wall Street Journal a few years ago. ”It doesn’t matter. They identify with it. It’s culturally such a big deal.”

Success for teams like the University of Alabama in the 1920s was a major point of pride for a region, six decades after the end of the Civil War, still trying to assert itself on the national stage. For one of the poorest parts of the US, continued success remains a point of pride to this day.

It’s just flawed enough to keep people entertained…

Sport, particularly in the US, is usually about athletic excellence. Yet the sustained appeal of college football seems to be more rooted in its tribalism. The game itself obviously is inferior in quality to pro-football, but that, Weinreb argues, is part of its appeal. ”The nostalgia of it, the imperfection of it, these guys are unformed beings… When you watch the NFL, it’s like you are watching people at work. With college you are watching people who are still striving to be something.”

…which, this being the US, makes it an enormously lucrative business…

This imperfection means that freak moments of brilliance, like this one from last year, seem to occur more often than they do in the hyper-efficient NFL.

But there’s also a dark side to the sport. Over the past few years almost all of the big college teams have been engulfed by scandals, ranging from the unseemly (numerous incidents where students are exposed as having accepted money) to the downright bizarre (a Notre Dame player whose “dead” girlfriend who turned out to be a very much alive male impersonator), to the truly horrific (a child abuse scandal, and allegations of a cover-up, at Penn State).

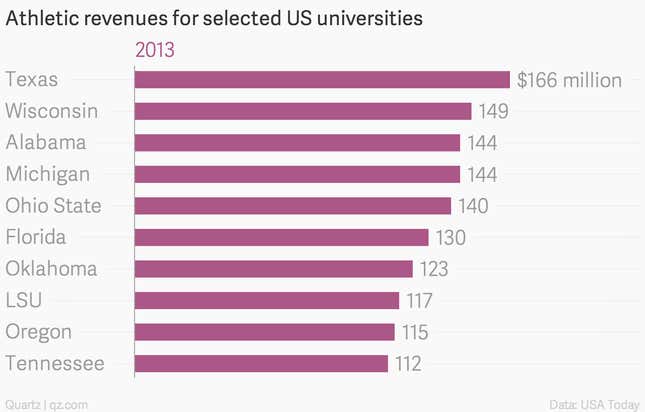

Yet these scandals have not dented college football’s popularity; quite the opposite. Its finances continue to shatter records each season. Revenues for the biggest programs now run into the hundreds of millions of dollars a year. The University of Alabama made more in athletics revenue last year than any US or Canadian professional ice-hockey team.

The biggest mini-leagues, or “conferences,” have multibillion-dollar TV rights deals in place; and the biggest games are played in front of vast crowds—a shrinking proportion of which are students (paywall). More than 50 million people attended college football games last year. The average game in the Southeastern Conference (SEC), widely regarded as the strongest conference, had an audience of more than 75,000. The University of Michigan’s average home crowd was 111,592.

The SEC has also just launched a TV station, the SEC Network, in partnership with sports channel ESPN. In a recent research note, Morgan Stanley estimated that this could bring Disney (which controls ESPN) at least $100 million next year in additional profit.

…just not for the actual players

The NFL is, somewhat incredibly, a registered nonprofit, paying no tax on its income. Not to be outdone, college football has an even less defensible business advantage: free labor.

Though scholarships can run into the tens of thousands of dollars each year, and football players could soon get stipends of up to $5,000 a season to cover incidentals like food and clothing, there have been calls for a while (paywall) for the athletes to get paid properly. One study in 2012 estimated that scholarships furnish only 17% (pdf, p. 3) of a college player’s fair market value.

So where do those billions in revenue go? In part to pay coaches (the highest-paid government official in many states is the football coach). In part to subsidize other student sports that make less money. And in part on an arms race to build the best stadiums and training facilities, to attract the best athletes, to sustain the success of the football teams, to generate more revenue, to pay the best coaches… and so on. “There is so much money in it now, that all these schools are building facilities just to build facilities just because the other schools are doing it,” Weinreb explains.

Earlier this year, football players at Northwestern University took steps to form a labor union that could allow them to bargain collectively for a greater share of the spoils. Also last year, the National Collegiate Athletic Association, the university sports governing body, and EA Sports, a video-game maker, agreed to pay a total of $60 million to former athletes whose likenesses were used in video games.

That might not result in big individual payouts to the thousands of athletes who have played college sports over the past decade, but it could set an important precedent as the first-time amateur student athletes are compensated for their work building a multibillion-dollar industry.

But it’s trapped in a vicious cycle…

Despite the massive revenue at stake, the arms race means that premier college sports could become a drain on university finances rather than strengthening them. Last year, in a report titled “Big-Time Sports Pose Growing Risks for Universities,” the credit ratings agency Moody’s estimated that 90% of college athletic programs are not self-sustaining. They require increasing subsidies, diverting funding from other needs. The huge capital-works programs (to build stadiums and awe-inspiring training facilities) they entail are often debt-financed, making it harder for universities to borrow to fund other investments.

Finally, the growing recognition of concussions and brain damage suffered by players means universities could face bigger long-term liabilities than they think. The violence of football has gotten so bad that there is a serious debate about whether watching the NFL is immoral. What does that say for college football, where players don’t even get paid?

As college football becomes more and more of a business, it also risks losing the qualities that drew people to it originally. Some of the bitter but exciting rivalries that have built up over decades are no longer played out, as colleges that used to be in different conferences have linked up to form more attractive groupings for television. This year, the sport will feature, for the first time, a formalized playoff system to determine a national champion—a move that may put to rest age-old debates over which is the best team, but which pushes the sport even further into professionalism.