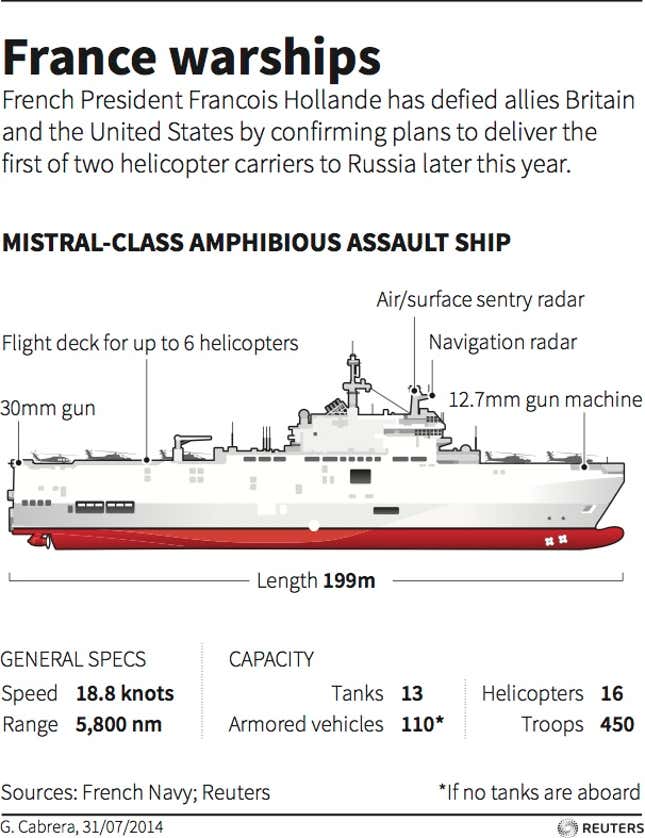

For months, French officials have deflected and deferred any discussion about a controversial deal to supply two advanced warships to Russia. The €1.1 billion ($1.5 billion) deal, signed in 2011, would see France deliver two of the Mistral-class assault ships to Moscow. The first, the Vladivostok, was due to change hands as early as next month. Russian troops even trained on the new ship in France this summer.

But a statement today from French president François Hollande—just hours after Russian president Vladimir Putin attempted to stave off sanctions by presenting a plan for a ceasefire in Ukraine—said that the deal has been suspended. Russia’s actions in eastern Ukraine “go against the foundation’s of Europe’s security,” the statement read. Whatever the prospects for a ceasefire between Ukraine and Russian-backed rebels, the conditions to deliver the warships are “not right.”

Even after several rounds of sanctions, travel bans, and asset freezes, this is perhaps the harshest penalty that any country in Western Europe has taken against Russia so far. It is only a suspension, rather than a cancellation, but the financial hit to France’s defense industry could be significant.

To date, EU sanctions against Russia have covered only future business, leaving existing contracts untouched. If any European country was going to voluntarily endanger current business deals, instead of things at some unspecified time down the line, few would guess that it would be France.

In imposing a potential billion-euro loss on a sensitive industry—to say nothing of the future costs of potential weapon buyers getting cold feet—Hollande has stuck his neck out further than other European leaders, including those who have talked tougher against the Kremlin than he has. Germany blocked the sale of combat gear to Russia last month, but that was worth less than a tenth of France’s warship sale.

Even after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its role in the escalating violence in eastern Ukraine, France was adamant that the deliveries would take place. (The second French warship is rather awkwardly named the Sevastopol.) “The rule is that signed and paid contracts are honored,” French foreign minister Laurent Fabius said recently. Earlier this week, Russian state media was trumpeting France’s resolve in sticking to the contract.

The suspension of the deal is important because “France has been one of the countries trying to contain the spiral of ever-increasing sanctions,” Antonio Barroso, an analyst who covers France for Teneo Intelligence, tells Quartz. “A strong decision needed to be taken, and [the warship deal] was the obvious candidate.” In other words, “at some point, France had to take a hit,” he says.

France’s move will give it more credibility among allies like the US and UK at the two-day NATO summit that starts tomorrow. Economically, it may also gain sympathy from the euro zone’s paymaster, Germany, with which it is locked in an increasingly bad-tempered debate over the merits of austerity.

Hollande’s move will also play well at home, Barroso says. His dismal approval ratings drove a cabinet reshuffle last week, with the president ejecting internal opponents of his policies in favor of more loyal deputies. This newly forceful stand abroad reflects a similarly resolute change of direction, away from the waffling and paralysis that has marked his presidency to date. France’s stagnant economy has fuelled the rise of far-right National Front, but that party’s staunch support of Moscow is an issue that Hollande’s socialists can use to win back disillusioned voters. This is a step in that direction.