Freshmen across the country are moving into their dorms this week, hanging up their Target Room Essentials™ curtains and sizing up their roommate’s hygiene habits. They might also, on the advice of their forebears, stop to Google articles such as, “15 Ways to Fight the Freshman 15.” In the course of this battle, they may vow to attend only the most rigorous Zumba sessions at the campus gym and to eat only the most reasonable servings of soft-serve from the campus soft-serve machine. At least until said machine is stolen by the Pi Kappa Phi brothers as part of an elaborate and tragically fatal prank.

It’s of course good to exercise and use portion control. But either way, these students will probably not gain 15 pounds. They will gain, research shows, just 2.5 to six.

Indeed, the Freshman 15 is largely folklore, known perhaps more for its alliterative allure than its scientific veracity. In other countries the first-year weight gain is known as the more vague First Year Fatties, the more accurate Fresher Five, or, in the case of Australia, the more explicit-sounding “Fresher Spread.”

In America, first-year weight-gain was originally known as the ”Freshman 10,” and it was presumably adjusted upward as Americans got bigger.

“She appeared to have what is known here as the ‘freshman 10,’ the 10 pounds many freshmen gain in their first weeks,” the New York Times sniffed in 1981 in an article about the first year at Yale for ”Miss Foster”—Jodie, that is.

The first article to reference the Freshman 15, meanwhile, was Seventeen magazine in 1989, in an issue whose cover featured 14-year-old supermodel Niki Taylor wearing a bright orange corduroy blazer. Before that, the only medical research to reference first-year weight-gain was a 1985 Addictive Behavior study in which the subjects gained an average of just 8.8 pounds. From there, references to the phenomenon bounced around in articles in Shape and American Cheerleader, few of which consulted experts.

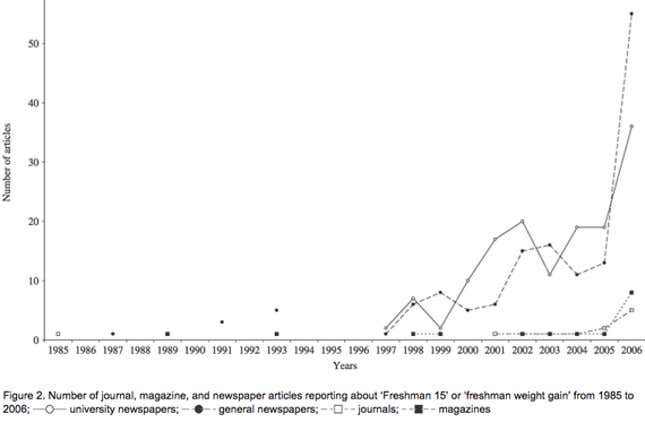

As more and more magazines and newspapers covered the trend, they neglected to mentioned that it was scientifically unsubstantiated, as University of Oklahoma Library Sciences professor Cecelia Brown found in a 2008 review.

Articles mentioning the Freshman 15 over time

By 1992, dietitians were referring to the “15” in news stories. A Washington Post article about college weight-gain that year noted astutely that “Vegetables, in particular, are not popular among students.”

Like many others, that piece ignored the most significant factor that actually contributes to college weight-gain: Heavy drinking. A 2011 study found that having six or more drinks on at least four days per month was the only thing that made a significant difference when it came to keeping one’s high-school figure. Even then, the drinkers gained just a pound more than non-drinkers did.

That same study found that in reality, just 10% of college freshmen gained 15 or more pounds, and a quarter of them actually lost weight. Instead, college students gain weight steadily throughout their time in school—women gain between seven and nine pounds total, and men gain 12 or 13.

Furthermore, the increase seems to be a natural part of adulthood, not something unique to dorms and dining halls. College freshmen gain just half a pound more than people their age who don’t attend college.

And this is not an isolated finding: A 2008 study found an average weight gain of 2.7 pounds. A 2014 study found no change in college students’ BMIs between the time they were admitted and the time they graduated. A total of 1858 subjects followed in 14 different studies averaged a gain of just 4.6 pounds during their first years. None came anywhere close to 15 pounds.

It’s not a bad thing to want to eat better, exercise, and try to stay healthy. It is a bad thing to live with “intense fears about gaining weight,” as many freshmen women now reportedly do. As Brown points out, “A fear of weight gain can lead to eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia, the incidences of which peak between the ages of 16 and 20, coinciding with the time young women enter university.”

To make the college transition a little easier, it might be time to retire our unfounded paranoia over a sudden bodily ballooning, just like we long ago retired our bright orange blazers.

This post originally appeared at The Atlantic. More from our sister site:

Not everyone can afford the all-American on-campus experience