China is the world’s biggest smartphone market. Google dominates that market, with nearly 85% of smartphones running a version of its Android operating system. Yet Google receives little benefit from its immense success there. Google Play, the company’s store for apps and more, does not work in China thanks to several diverse and ad hoc bans on Google’s services. And many device-makers either alter Android so much as to render it unrecognisable or delight in being able to break free of Google’s strict rules and offer their own app stores.

Everything but the factories

Google wants to ensure that doesn’t happen in India, where smartphone penetration is exploding. This morning, Google launched the first new phones in its Android One program. They come with a 4.5-inch display (just shy of the new iPhone 6), 4 gigabytes of internal storage, a 5-megapixel camera, replaceable batteries, an SD-card slot, two SIM slots, and FM radio. They cost $105.

The details of new devices such as this one suggest that Google has carefully studied what Indian consumers want. Large screens are popular across the developing world because poorer consumers want a device that can fulfil many functions; phones that take two SIM cards are popular in emerging markets as consumers take advantage of differing rates of different networks; Indians typically avoid downloading or streaming content and instead load media onto removable SD cards; the new devices allow users to download YouTube videos for later consumption; and so on. Google provides the specifications to local brands, which then make and distribute the devices.

Yet Google’s phones are not that different from the phones they will compete with, which include the Xiaomi Redmi (Rs 5,999/$98) HTC Desire 210 (Rs 6,525/$107), Moto E (Rs 6,999/$115), and Micromax Unite 2 A106 (Rs 6,750/$110). These have similar, if not better specifications, than Google’s devices.

Going where the growth is

So what is the point of this exercise? It boils down to two crucial areas for Google. First, Google wants to ensure that Indians do not shun the Google ecosystem in favor of home-grown app stores, like their counterparts in China. India does not ban Google services like China does, but this is still an issue because many Indian mobile internet users go to app and content stores set up by mobile operators rather than Google, according to Opera Mediaworks, a mobile ad platform.

One big reason for this is customers already have a billing relationship with their carriers. Large swathes of India lack access to formal banking, which means they are unable to pay for online content using credit cards. Mobile operators allow them to pay in cash. Several industry insiders have suggested that Google will eventually tie up with operators to bill Android users for purchases on the app store.

Android One thousand

The second big reason Google is spending money designing phones for Indian smartphone makers is to address the issue of fragmentation—where mobile users are running several different versions of an operating system. This is more of an issue in markets where Android dominates: More iPhone users worldwide upgraded to iOS 7 within three days of its release in September last year than Android users had in the entire month after Google pushed out its own update.

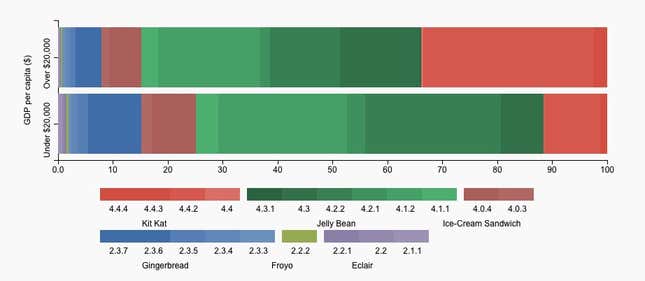

And in emerging markets, fragmentation between operating system version is even more acute. Cheap smartphones sold in poorer parts of the world are often incapable of handling more advanced versions of Android. Indeed, looking at Android versions in use in any country can work as a rough proxy for how rich that country is, as the chart above shows.

This matters because fragmentation makes life difficult for app developers. If they want to address the bulk of Android users, they need to ensure their apps work across devices, screen sizes and operating systems. It is a messy job.

Android One is Google’s solution to both these problems. Google designed the phone to be able to run the latest software, as well a forthcoming update. Google’s deals with operators mean that many users will not have to pay data charges to download the new version. Nor will they be charged for the first 200 MB of apps that they download from Google Play. This is a retread of the old zero-rating story—web firms and mobile operators agree to provide some services, such as Facebook or Google search, for free in the hope that it will increase usage of these services and data consumption as a whole—but for apps and updates rather than web browsing.

Will it work? The Android One phones are manufactured by well-known domestic brands Micromax, Karbonn, and Spice. They offer impressive value for money. And they come certified with the Google stamp, an important feature in a country that has a soft spot for foreign brands.

Yet there is already some tension between Google and the device makers. Medianama, an Indian tech website, reports the brands making the phones are already seeking more control from Google. That is not an auspicious start.