China’s not stimulating its economy. It’s just keeping it from freezing up

Yesterday, the People’s Bank of China leaked to the press that it had pumped 500 billion yuan ($81 billion) into its financial system. Exciting news, coming in the wake of a batch of recent data showing the rapid withering of the Chinese economy. “Is this the China stimulus we’ve been waiting for?” asked CNBC. Copper traders seemed to think so; futures prices for the red stuff leapt 4% after media reported the event as a “stimulus” and ”credit expansion.”

Yesterday, the People’s Bank of China leaked to the press that it had pumped 500 billion yuan ($81 billion) into its financial system. Exciting news, coming in the wake of a batch of recent data showing the rapid withering of the Chinese economy. “Is this the China stimulus we’ve been waiting for?” asked CNBC. Copper traders seemed to think so; futures prices for the red stuff leapt 4% after media reported the event as a “stimulus” and ”credit expansion.”

But those are mischaracterizations. Instead, the injections are the sort of ”run-of-the-mill operations” that keep enough money in the system, notes Capital Economics.

The worry is that if big banks fear a cash shortage, they’ll hoard money. Mid-sized banks—which are much more reliant on interbank lending for funding—might default on their obligations to other banks. So debt-sodden are Chinese businesses that if banks stop lending to each other—and, hence, to businesses—many will default on loans. And since China still doesn’t have deposit insurance, it could spark a bank panic—and ultimately a financial crisis.

That doesn’t mean China’s on the brink of such a catastrophe (or at least, not any more so than usual). So why inject $81 billion now?

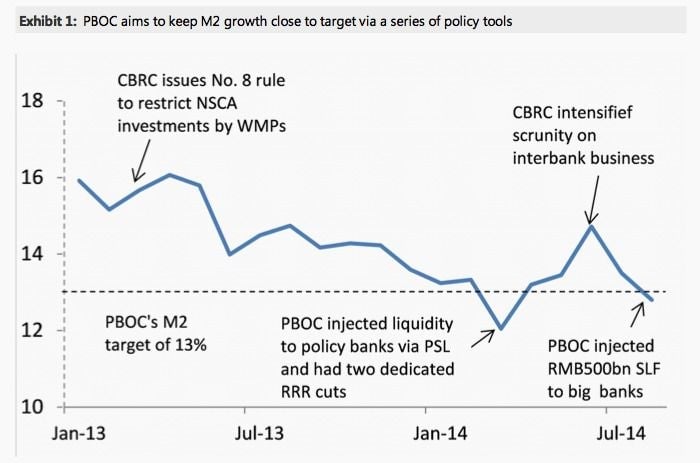

One possible reason is China’s money supply just dipped below the target 13% annual growth rate, notes Morgan Stanley’s Richard Xu. He adds that the PBoC has been injecting money more often in 2014—particularly whenever the banking regulator scrutinizes shadow banking, the off-balance-sheet channels that are keeping many banks liquid. Here’s the recent trend in the annual growth of money supply (M2):

Seasonal spikes in money supply are another factor, says Xu. Money often tightens up before holidays as banks gather up the cash their customers will need while money markets are closed. Not only is China fast approaching the weeklong Nation Day holiday, but we’re also coming up on the end of the quarter, when banks must produce cash to pass regulatory muster.

Though some analysts likened the PBoC’s injection to “quantitative easing,” that’s not exactly right. The goal of QE for the Federal Reserve was to lower mortgage rates and long-term borrowing costs. Pumping more money into the system was a byproduct.

In China, it’s the converse. The PBoC must keep banks flush with cash; rates fall as a result. The latest injections are reportedly three-month loans, too short to boost bank lending. If the PBoC were “stimulating,” it would, as it did months ago, slash banks’ reserve ratio requirements. But that would whip up inflation, re-inflate the housing bubble, and increase the chance of a debt crisis.

This distinction highlights how much more crucial money supply is for China’s financial system.

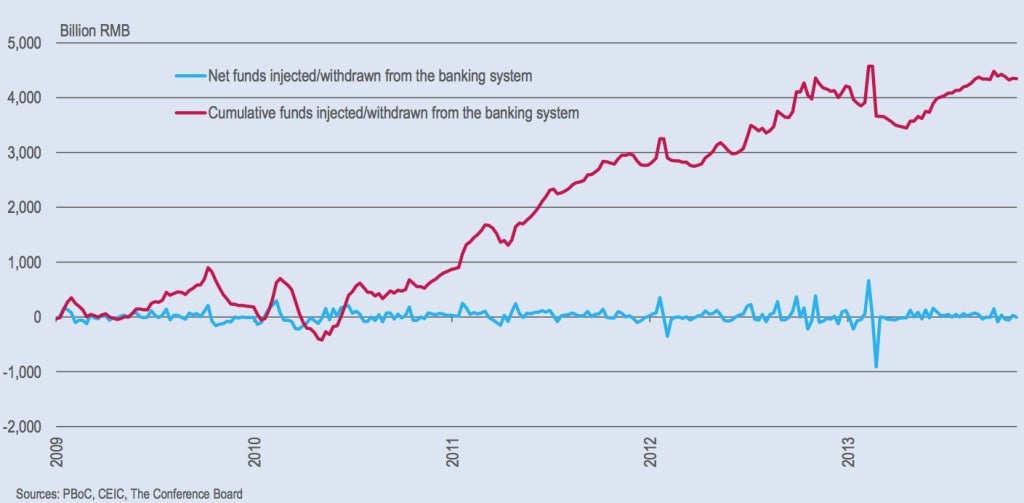

China is more addicted to cash because its government, not the market, controls interest rates—and it manipulates them to benefit borrowers, which penalizes savers. Reducing money supply would shift money back to savers, helping boost consumption and the balance of global trade. But thousands of highly indebted businesses and banks need that surge of cash to avoid default. This chart from the Conference Board shows just how big that surge has been.