Corporations are tempted to take over journalism with increasingly better content. For the profession, this carries both dangers and hopes for new revenue streams.

Those who fear native advertising or branded content will dread the unavoidable rise of corporate journalism. At first glance, associating the two words sounds like of an oxymoron of the worst possible taste, an offense punishable by tarring and feathering. But, as I will now explain, the idea deserves a careful look.

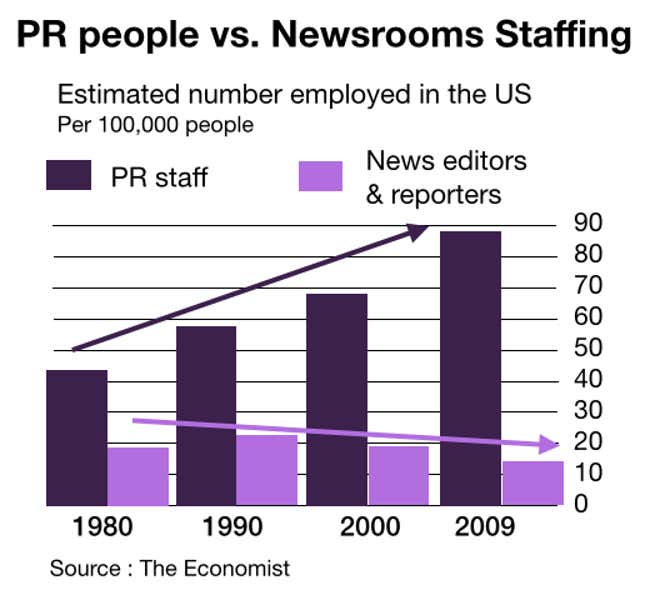

First, consider the chart below, lifted from an Economist article titled “Slime-slinging; Flacks vastly outnumber hacks these days. Caveat lector,” published in 2011. The numbers are a bit old (I tried to update them without success), but the trend was obvious and is likely to have continued:

Update: As several readers pointed out, I failed to mention a Pew Research story by Alex T. Williams that contains recent data that further confirm the trend: (emphasis mine)

There were 4.6 public relations specialists for every reporter in 2013, according to the [Bureau of Labor Statistics] data. That is down slightly from the 5.3 to 1 ratio in 2009 but is considerably higher than the 3.2 to 1 margin that existed a decade ago, in 2004.

[Over the last 10 years], the number of reporters decreased from 52,550 to 43,630, a 17% loss according to the BLS data. In contrast, the number of public relations specialists during this timeframe grew by 22%, from 166,210 to 202,530.

Williams also exposes the salary gap between PR people and news reporters:

In 2013, according to BLS data, public relations specialists earned a median annual income of $54,940 compared with $35,600 for reporters.

And I should also mention this excellent piece in the Financial Times on The invasion of Corporate News.

In short, while the journalistic staffing is shrinking dramatically in every mature market (US, Europe), the public relation crowd is rising in a spectacular fashion. It grows in two dimensions: the spinning aspect, with more highly capable people, most often former seasoned writers willing to become spin-surgeons. These people are both disappointed by the evolution of their noble trade and attracted by higher compensation. The second dimension is the growing inclination for PR firms, communication agencies and corporations themselves to build fully-staffed newsrooms with editor-in-chiefs, writers, and photo and video editors.

That’s the first issue.

The second trend is the evolution of corporate communication. Slowly but steadily, it departs from the traditional advertising codes that ruled the profession for decades. It shifts toward a more subtle and mature approach based on storytelling. Like it or not, that’s exactly what branded content is about: telling great stories about a company in a more intelligent way instead of simply extolling a product’s merits.

I’m not saying that one will disappear at the other’s expense. Communication agencies will continue to plan, conceive and produce scores of plain, product-oriented campaigns. This is first because brands need it, but also because there are often no other ways to promote a product than showing it in the most effective (and sometimes aesthetic) fashion. But fact is, whether it is to stage the manufacturing process of a luxury watch, or the engineering behind a new medical imagery device, more and more companies are getting into full-blown storytelling. To do so, they (or their surrogates) are hiring talent—which happens to be in rather large supply these days.

The rise of digital media is no stranger to this trend. In the print era, for practical reasons, it would have been inconceivable to intertwine classic journalism with editorial treatments. In the digital world things are completely different. Endless space, and the ability to link and insert expandable formats open new possibilities when it comes to accommodating large, rich, multimedia contents.

This evolution carries both serious hazards for traditional journalism as well as tangible economic opportunities. Let’s start with the business side.

Branded content (or native advertising) has achieved significant traction in the modern media business—even if the quality of its implementation varies widely. Some companies (that I will refrain from naming) screwed up big time by failing to properly identify what was paid-content as opposed to genuine journalistic production. And a misled reader is a lost reader (especially if there is a pattern). But for those who pull out good execution, both in terms of ethics and products, native ads carry a much better value than banners, billboards, pushdowns, interstitials, or other pathetic “creations” massively rejected by readers. I know of several media selling dumb IAB formats that find out they can achieve rates 5x to 8x higher by relying on high quality, bespoke branded contents. These more parsimonious and non-invasive products achieve a much better audience acceptance than traditional formats.

For media companies, going decisively for branded content is also a way to regain control on their own business. Instead of getting avalanches of ready-to-eat campaigns from media buying agencies, they retain more control on the creation of advertising elements by dealing with the creative agencies or even with the brand themselves. Such a move goes with some constraints, though. Entering branded content at a credible scale requires investments. To serve its advertising clients, BuzzFeed maintains 50 people in its own design studio. Relative to the size of their entire staff, many other new media companies decided from the outset to build fairly large creative teams (including Quartz). That’s precisely why I believe most legacy media will miss this train (again). Focused on short-term cost control, also under pressure from conservative newsrooms who see branded content as the Antichrist, they will delay the move. In the meantime, pure players will jump on the opportunity.

Newsrooms have reasons to fear corporate journalism—the ultimate form of branded content entirely packaged by the advertiser—but not for the reasons editors usually put forward. Dealing with the visual segregation of native ads vs. editorial is not utterly complicated; it depends mostly on the mutual understanding between the head of sales (or the publisher) and the editor; the latter needs to be credible enough among his peers to impose his/her choices without yielding to corporatism-induced demagoguery.

But the juxtaposition of articles (or multimedia contents) produced on one side by the newsroom and on another hand by a sponsor willing to build its storytelling at any cost might trigger another kind of conflict, around means and sources.

In the end, journalism is all about access. Beat reporters from a news media will do their best to circumvent the PR fence to get access to sources, while at the same time the PR team will order a bespoke story from its own staff writers. Both teams might actually find themselves in competition. Let’s say a media outlet wants to write a piece on the strategy shift of major energy conglomerate with respect to global warming; the news team will talk to scores of specialists outside the company, financial analysts who challenge management’s choices, shareholders who object to expensive diversification, advocacy groups who monitor operations in sensitive areas, unions, etc. They will also try to gain access to those who decide the fate of the company, i.e. top management, strategic committees, etc. Needless to say, such access will be tightly controlled.

On the corporate journalism side, the story will be told differently: strategists and managers will talk openly and in a very interesting way (remember, they are interviewed by pros). At the same time, a well-crafted on-site video shot in an oil-field in Borneo, or on a solar farm in Africa will reinforce the message, in a 60 Minutes way. The whole package won’t carry silly corporate messages, it will be rich, carefully balanced for credibility and well-staged. Click-wise, it is also likely to be quite attractive with its glowing, sleek videos and great text that will have the breadth (but not the substance) of professional reporting.

I’m painting this in broad strokes. But you get my point: Authentic news reporting and corporate journalism are bound to compete as audiences increasingly enjoy informative, well-designed corporate production over drier journalistic work—even though it is labelled as a corporate production. Of course, corporate journalism will remain small compared to the editorial content produced by a newsroom, but it could be quite effective in the long run.

You can read more of Monday Note’s coverage of technology and media here.