To understand what makes South Africans tick, just watch the ads for its most loved export: flame-grilled chicken. Since opening 25 years ago, local fast-food franchise Nando’s has become a successful global business. It also happens to be beloved here for politically irreverent advertising campaigns that lampoon everyone, president to pauper.

Nando’s story is the stuff from which brand legends are built. It started in 1987 when Robbie Brozin and Fernando Duarte bought an eatery in a small Johannesburg suburb for the love of its peri-peri flame-grilled chicken, prepared Portuguese style. They got the shop, the secret recipe and ran with it—launching not just an eatery but what Forbes in September recognized as one of Africa’s most innovative companies.

By numbers alone, KFC is winning with at least 600 outlets in South Africa. But it has little of Nando’s creative muscle. Compare these advertisements. The first is KFC’s recently released five-episode Face Yoga campaign for its Krusher smoothies:

They come off as overproduced and unnecessarily long. Here’s one of Nando’s “25 Reasons” ads, released with its anniversary celebration:

This simple resonance has won South Africans over—if only for making South Africans laugh at themselves. The privately held chain, which operates more than 1,000 stores globally, including Australia, Bangladesh, the US and Malawi, is not afraid to tinker with the elements that hold this robust but fragile nation together. Just last month when the spokesperson for the Hawks, South Africa’s special crime-fighting unit, McIntosh Polela, embarrassed himself on Twitter, Nando’s had the last laugh. Polela was lambasted for posting a joke about prison rape in reference to the murder conviction of music celebrity, Molemo “Jub Jub” Maarohanye. The murder and ensuing two-year trial shocked the country. Nando’s’s comeback: “You shouldn’t tweet when you’re hungry, McIntosh.”

The humor is hardly off the cuff, rather the result of careful, deliberate strategy. For example, the Twitter response went through creative, marketing, and advertising teams before it went live. Nando’s marketing manager, Thabang Ramogase, phoned his Johannesburg-based advertising agency Black River FC: “There is this thing going around on Twitter and I want you to comment on it.” Black River executive creative director Ahmed Tilly said the agency worked on some retorts, and gave Nando’s two options before it selected the one to tweet.

This tactical marketing approach has become synonymous with the brand, and the company has come to “own it,” says Tilly. Nando’s has its thumb fully and firmly on the pulse of the nation, magnifying our country’s political and social absurdities. Its 25-year history has spared no one: black and white, men and women, even the blind so much that political parody has become its DNA.

Nando’s succeeds at capturing the mood of the country in key historical moments. Consider the panic of white people at the advent of a new South Africa before the 1994 democratic elections, facing a reality they never thought possible after years of free and corrupt reign—a black-majority rule and a black president (Nelson Mandela). “White people were stockpiling and building bunkers because they were afraid of the new dispensation,” says Anthea Whitehead, faculty head at AAA’s school of advertising’s Cape Town campus. And then came this ad:

The “Never Seen Before” TV ad of a black man driving a truck carrying white workers remains an unlikely site in South Africa even today, but set a tone for the brand’s early work. There was a lot more controversy in advertising in those days and it was more political, adds Whitehead. Throughout the years Nando’s has remained “very politically inclined,” she says.

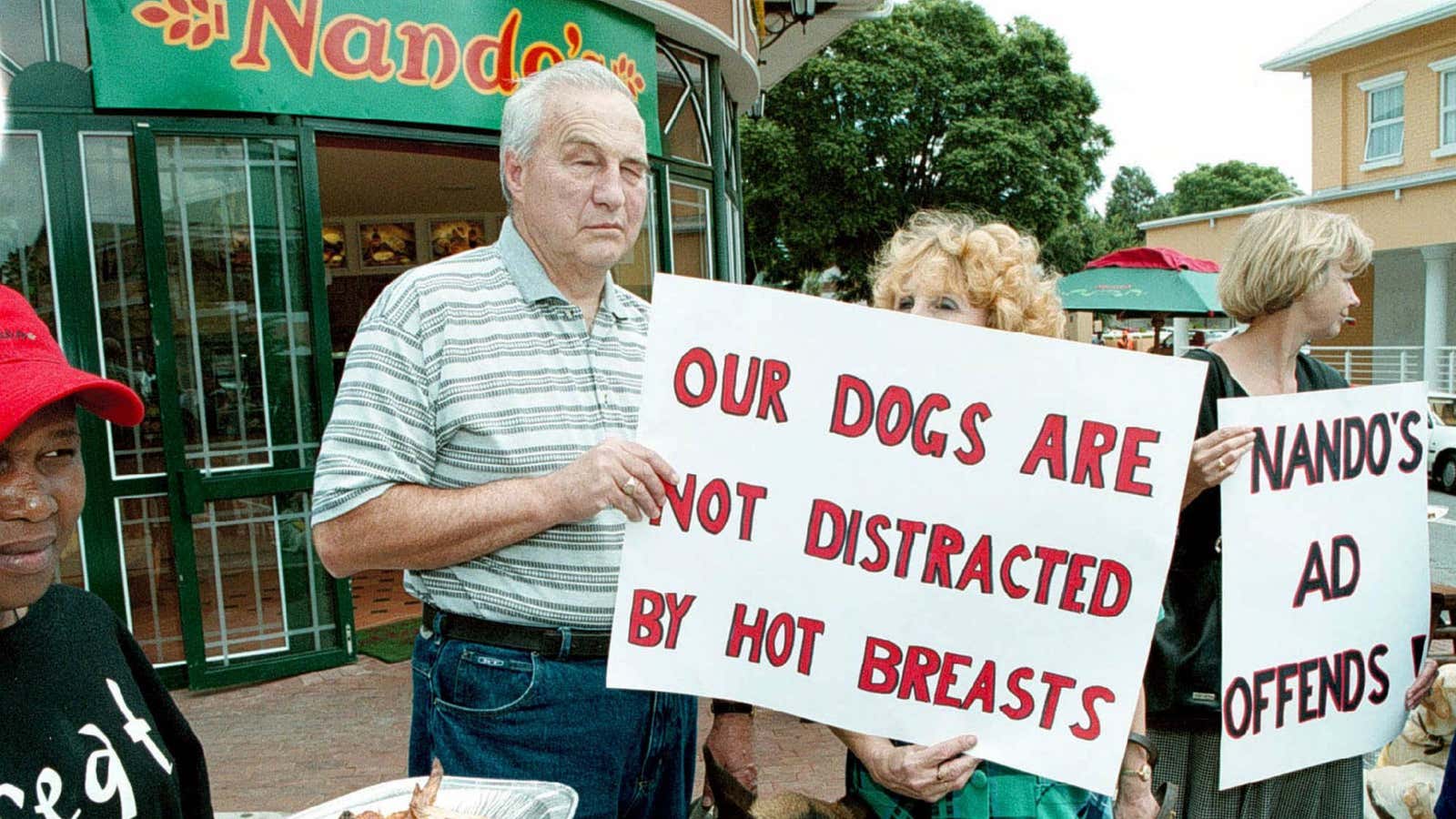

Political satire is a style that helps the brand live in the nation’s consciousness, although not without contention. This campaign, called “Diversity,” tackled the country’s xenophobia and targeting of immigrants. As happened with the ad of the blind person in the year 2000, which sparked protest over saving the reputation of guide dogs, public and private broadcasters pulled it from the airways.

The ad, which now only lives online and ranks No. 2 among the company’s most viral campaigns, might have sparked polarizing views, but it actually also fulfilled business objectives. “A lot of people say it’s got nothing to do with the product—it’s got nothing to do with chicken,” Tilly says. But the ad was meant to respond to criticisms that Nando’s serves more than just chicken. “People were saying that our menu was quite limited. We did not start with xenophobia and then find a way to squeeze the chicken in,” he says.

For Ramogase, the ads might have been yanked but they represent a dual victory: “Not only did we overshoot the volume targets of the newly introduced peri-crusted wings four-fold and deliver overall growth versus the previous year in the upper teens, we got South Africans to critically assess their own attitudes to what constitutes foreigner status in South Africa.”

But the most viral ad is this one, released before Christmas last year:

Here’s the political context: The Robert Mugabe regime in neighboring Zimbabwe has been a thorn in the side of South Africa as the latter country faces accusations it turned a blind eye to oppression. This ad shows Mugabe setting the table and reminiscing about better times with now-dead dictators such as Saddam Hussein, Muammar Qaddafi, Idi Amin, and apartheid leader P.W. Botha. As it showcases its six-pack meal, Nando’s tagline: This time of year, no one should have to eat alone.”

Besides a send-up to the Mugabe regime, Ramogase says, “it also, ironically, saw the Zimbabwe business deliver its best December in the history of the brand in that region.”

Of course, that the chicken tastes good is core to Nando’s success. Tilly calls founder Brozin a “legend in South African circles and globally. … He has to stick to the knitting. So what they have done consistently is to give consumers delicious flame-grilled chicken that it marinated for 24 hours, and have peri-peri sauce.”

Cool marketing strategies aside, “they are not going to sell more chicken than KFC,” says Whitehead. Nando’s feeds around 40 million customers around the world annually; KFC serves 12 million a day. The company operates in what they call the “fast casual chicken space,” so it takes a bit longer to prepare a meal and eateries are conducive to sit-down meals (with real crockery and cutlery and bottled condiments) over take-out and plastic and paper utensils. Plus, Nando’s sells better quality and better prepared chicken. In South Africa, KFC still represents a mammoth success story, with a menu targeting a diverse customer base: the middle-class suburban mom (R159.60, about $24, Variety Bucket with chips) to the young teen in the townships (a R24,90, about $4, Streetwise 2 of two pieces of chicken and chips). Nando’s price points are not that different: R159.90 Nando’s Full Pack meal of a whole chicken, chips, rolls, and salad, and R33.90 for the quarter chicken, chips, and roll.

“If you look at Nando’s ad spend versus that of KFC, it is minute,” Tilly says. “So you’ve got to work that much harder. You’ve got to punch above your weight.” It is position Nando’s has come to exploit with aplomb. Case in point: this Sanlam bank advert featuring Sir Ben Kingsley that took itself way too seriously.

In the ad below, Nando’s proves that big money and a knighted thespian do not necessarily make for an engaging campaign, but they are easy to spoof:

Nando’s expansion of its vision to other markets involves simply consulting with them on how to bring their own flavor to central campaigns. In most cases, the franchises run their own advertising and marketing.

In its home of South Africa, though, Nando’s has firmly fused its brand with the country’s identity. Whether this entrepreneurial spirit is enough to win over the world’s biggest consumer market is to be seen. But guided by Brozin’s business motto to “Have fun, and make money,” Nando’s is hardly in the business of just selling chicken by the bucket loads. It’s forcing a country to laugh—and look—at itself.