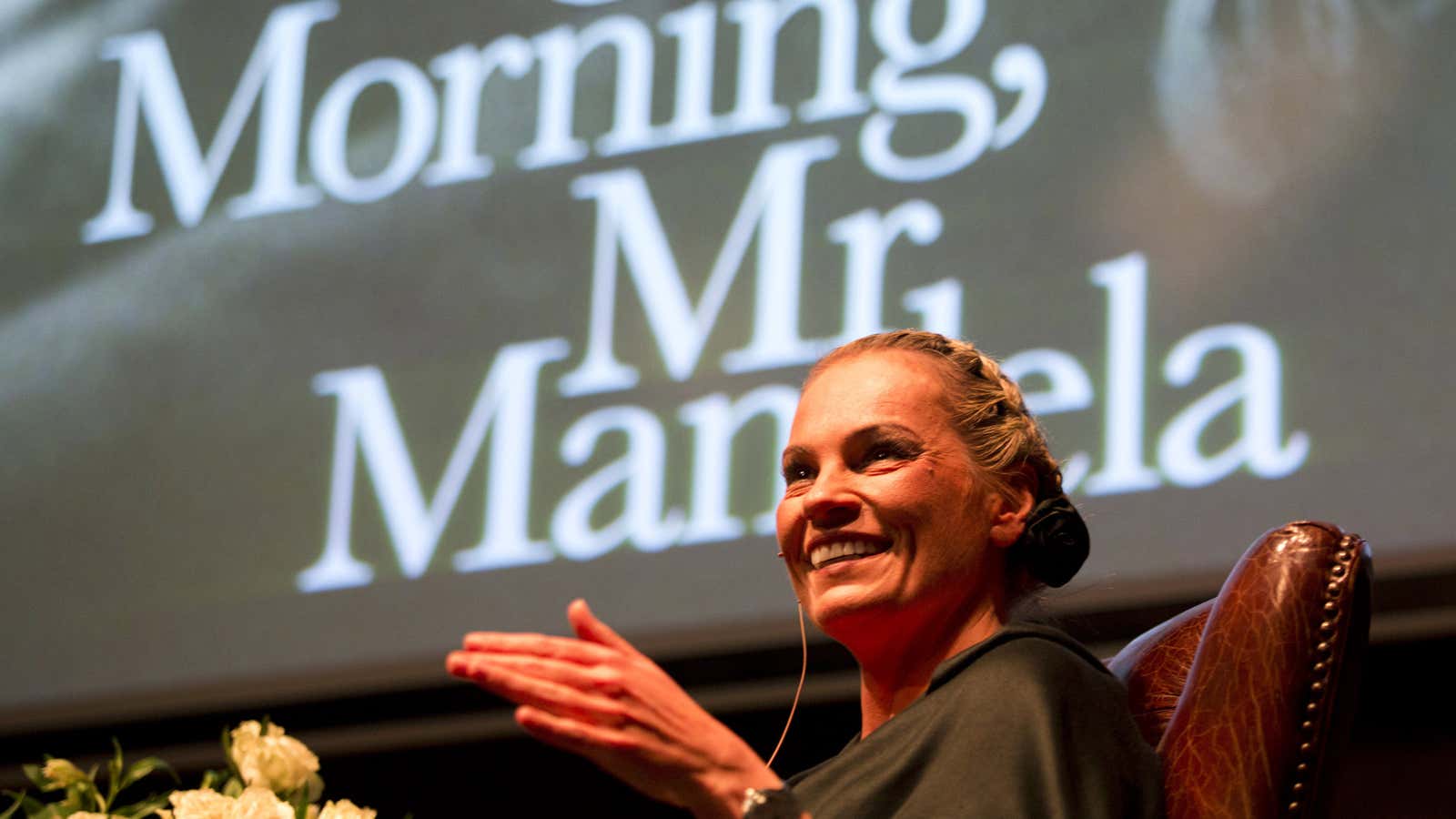

For me Zelda La Grange’s Good Morning, Mr. Mandela, long and repetitive, was a labor to read. But it’s been called a great success for good reason: it’s an important edition to the Nelson Mandela canon. La Grange adds to the account of Nelson Mandela as a man, not an icon: The distant father, whose absence must have sowed seeds of resentment in his kids; the lonely man who was comforted by the love of a younger woman, and at the end, the old man losing the grip on his mind and his family. Good Morning, Mr. Mandela’s unassuming power then is in its author’s unabated openness.

La Grange was the orbit to Nelson Mandela’s moon. She became his personal assistant in her early 20s and served in this post until late into his retirement when some members of his family sidelined her as he was losing his faculties. His reliance on her served to deepen the distance between him and some family, which it would be safe to assume had already existed. He was twice divorced, a political prisoner, then a busy statesman throughout his family’s life. You feel the family’s void in the book, in which the descendants are mentioned a handful of times, and mostly at the end, when “the poison from his family was leaking out everywhere.”

“Mary (Mxadana, Mandela’s first private secretary) also spent more time with me and told me about the president’s private life; his failed marriage to Winnie Madikizela and about their daughters, Zindzi and Zenani. Apart from official events where the president needed a companion and he would ask Zindzi or Zenani to join him, I rarely saw them, and judging from his diary one realised that the president didn’t have much time for a private life. I was also told that he has two surviving children from his first marriage but we never saw them or had any dealings with them.”

La Grange’s constant presence as de facto daughter—she called him Khulu (granddad) and he affectionately called her Zeldina—must have grated on those children. In the book it seems Mandela found his home not in the family he left behind, but in new faces, one of which was Grace Machel, the woman he married on his 80th birthday (she was 53). He called her Mum, and she “enlightened his life …” He would set his clock to her time zone so they could speak wherever he was in the world, in the mornings and evenings. But by the the end of his life, there was a lot of resentment within the family, and Machel was often at the receiving end, sidelined and humiliated by some in the family, La Grange says.

Tensions also arose in his relationship with Thabo Mbeki’s presidency, the ANC leadership that followed his. On his way to London to attend his 90th birthday celebrations, the SA High Commission refused him the use of the VIP room in Heathrow, something that they had approved before. “The sudden change of decision that a former head of state of South Africa was no longer allowed the courtesy of the support of the foreign mission to move through a VIP room had to be changed at cabinet level as far as I was concerned,” La Grange writes. But the ANC was exploitative of him when they needed him, she suggests, like when they filmed and broadcast an ailing and clearly unhappy Mandela with senior ANC members. It was a move that seemed like an electioneering ploy and it outraged the public.

The author never accords Mandela blame, not directly anyway, but in her openness she reveals a lot of his failings like his naiveté when it came to managing the flow of money. “During his fundraising days for the ANC the moneys would simply be handed from one official to the next and he never mistrusted anyone in the process.” Mandela knew nothing about investments or banking, she writes. “I would ask Madiba …whether anyone ever kept a record of the money. I was not suspicious of anyone but found it surprising that Madiba himself did not know how much money he really raised.” He was a bad administrator, too, meaning that some of the schools and clinics he built lay in waste because they were not managed properly.

At the end of his life, Nelson Mandela was not, as you would imagine, surrounded by his many children. He was lonely and isolated. La Grange reveals that he would concoct reasons for going to the mall, to get a book he would never read or a pen he did not need just so he could be “among people.” He would call her from home when he was about to take an elevator to the ground floor of his house because he was afraid of being stuck. “At the time I thought it was funny but now I become sad when I think of it. Being there and answering those calls made me love the man even more, perhaps the fact that he depended upon me, yet it is exactly that admiration and love that caused so much animosity.” In her account of his life La Grange brings the man, who’s become larger than life, down to size, and dusts some shine off his image. In the recurring detail of the countries crossed, celebrity hands shaken, are morsels of a figure for each of us to complete our own picture of his life.

Just last week I attended a talk on the life of Steve Biko, the Black Consciousness leader who might have been our first black president had he not been murdered in 1977. His comrade, Peter Jones, the man who was arrested with him when he was killed in detention, talked of a need to allow true stories of Biko’s life to be told, that we should not rely on the dominant discourse. La Grange, I think, has done just that for Mandela.