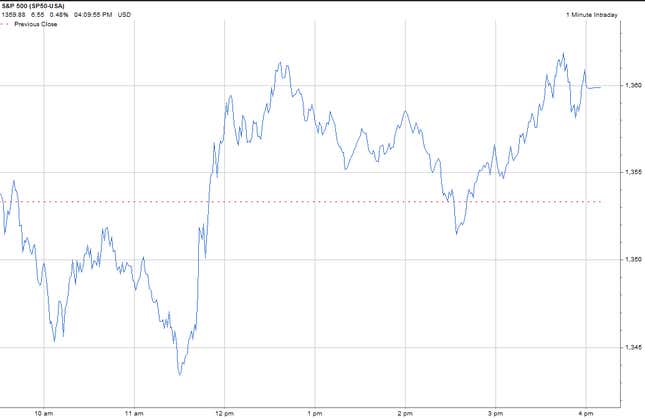

With news at the end of last week that the political leadership is sanguine about the prospects of avoiding the Jan 1. austerity trigger, the markets popped 15 points, about half a percent up on the day, at the end of trading:

While one stock analyst told the FT that the rebound is a signal that “investors are desperate for a deal, any deal,” there is a case to be made that the markets have yet to “price in” the risk of austerity policies and might not be paying attention, confident that the government won’t allow an unnecessary recession. Most analyst reports do lay odds on Democrats and Republicans agreeing on some kind of solution to the fiscal cliff, but the S&P 500 had dropped nearly 5% since the election until this rebound, and US Treasury note yields are noticeably lower—a sign that investors are at least a little nervous about next year.

Still, that might be expected. There’s no question that any deal will involve some near-term fiscal consolidation. Stimulus measures like the payroll tax cut and unemployment insurance will expire. Smaller tax increases that are part of health care reform will kick in. Together these will represent fiscal drag of about 1% of GDP, on growth that was already forecast to be slower than in 2012.

However, if markets are indeed caught napping and the Jan. 1 deadline rolls around without a deal—a scenario that S&P says has a 15% probability—what will happen? Spending and tax cuts won’t have much impact right away, but could the surprise be enough to send complacent CEOs into cost-cutting mode and panic the stock markets the same way that a failed first vote on the 2008 TARP bill (George W. Bush’s finance-industry bailout) did?

It’s an unlikely comparison. In 2008, the US was a good nine months into a recession and in the midst of a financial crisis, with major financial institutions going under. When the vote on TARP failed, it was seen as a sign that more banks could fail. If a vote on the fiscal cliff deal fails before Jan 1., business will face a mild recession in the following six weeks. That isn’t positive—but it’s not like wondering whether or not ATMs will still be working.

A better example was the last manufactured crisis: the debate over raising the US debt ceiling in the summer of 2011. Then as now, bipartisan dealmaking was needed to avert a legislative mechanism that would impose instant austerity. When initial efforts failed—leading to the automated fiscal cliff that we have now—stocks dropped, but nowhere nearly as severely as 2008, even as punting on fiscal consolidation made it cheaper for the US to borrow. True, months of volatility followed, but that was partly because of the European crisis and the concerns about growth.

The bond markets today aren’t demanding consolidation, either. Investors aren’t concerned about the United States ability to to make payments, nor should they be—yields remain at historic lows thanks to the actions of the Federal Reserve and the relative strength of the US economy.

Equity markets are a bit more nervous, since a mild recession would hurt US companies’ earnings—and that explains their little jump at the end of last week. But how they behave in general over the coming weeks will depend far more on whether there is good news from the talks themselves than whether or not the deadline is passed; right now, they don’t seem too concerned.

In any case, since the government can juggle spending obligations to delay the impact of spending cuts, and the incentive for both sides to make a deal only increases after Jan. 1 has come and gone, even the lack of a deal by that date might not rattle the markets too much. So what would make them sit up and take notice? Perhaps Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner, who can decide whether tax withholdings should be at their pre- or post-fiscal cliff levels in the new year, depending on how likely a deal looks. If he chooses post-cliff, and people immediately feel the bite of higher taxes in their paychecks, it could spur fears of recession and a sell-off that would, at last, scare Washington into action.

But so far at least, lawmakers have been saying the right things, and the markets have been responding appropriately. And if the time comes to panic, rest assured: they will.