Leaked documents are revealing how multinational corporations use the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg as a financial way-station to avoid taxes.

The trove, published by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, contains tax returns and tax structure proposals prepared by the global accounting firm PWC and approved by the government of Luxembourg. These actions aren’t illegal unless they violate international standards, but some of these new documents will add to the impression that the rules were not taken seriously—after all, the country’s former top tax official, Marius Kohl, told the Wall Street Journal that he did not verify the company’s transfer-pricing models.

Observers have long understood the financial business model of European havens like Luxembourg—and PWC’s involvement. These documents provide concrete evidence of how companies like Apple, Verizon, Caterpillar and hundreds of others created cozy deals in the tiny country, to avoid taxes in places elsewhere in the European Union and in the US.

Hypocrisy watch

One person getting heartburn from these leaks is Jean-Claude Juncker, the current president of the European Commission—and former prime minister and finance minister of Luxembourg. The EC is currently investigating Ireland for negotiating cozy tax deals with Apple, and the key argument is that Ireland didn’t force Apple to meet the standards for conducting transfers between related subsidiaries, known as “arm’s length.” This may end with billions of dollars in back tax payments for Ireland and Amazon.

But according to Apple’s 2011 tax filing in Luxembourg, prepared by PWC, the same practice could be at work in his home Duchy:

How it’s done

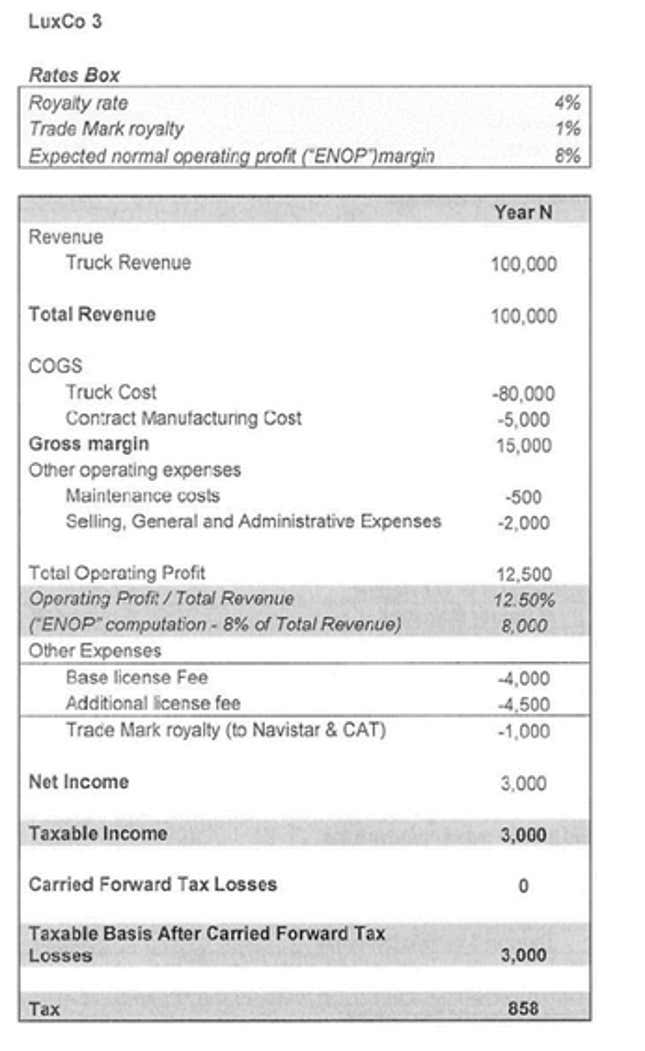

One of the nice things about these documents is that the accountants are coming out and explaining how it all works, for the benefit of Mr. Kohl. Caterpillar, the American heavy-vehicle manufacturer that even has its own tax whistleblower, had a joint venture with Navistar, another American heavy-vehicle maker, until 2011, though the companies still have significant business relationships. In 2010, here’s how PWC explained the tax effects of a complex structure, including four Luxembourg subsidiaries, on the sale of a hypothetical $100,000 truck:

Reading down until “total operating profit,” you see pretty normal accounting, deducting expenses from revenue. But then things get interesting: First, the company has an agreement with Luxembourg that it will only make an 8% profit from this company—anything over that is paid as a tax-free license fee to another subsidiary, besides the 4% licensing fee it pays for its own intellectual property to that same subsidiary. Then, there’s a different royalty paid for the use of the company’s brand to a different property. All that chops the taxable profit on the sale of this truck by 75%.

Who is doing it

It’s fairly obvious, of course: There are really only four global accounting firms that work with multinational companies, and critics say that what was once a sober profession has become increasingly driven by short-term profits, with the commensurate incentive to push the boundaries of ethical and legal behavior. They have become the “central architects of the global offshore system,” and government interest in their activities has risen as well: Besides PWC’s involvement in Luxembourg tax shelters, anti-corruption activists allege that Deloitte helped hide “conflict gold” in the Middle East, and US authorities have dinged KPMG for peddling tax shelters and investigated Deloitte and PWC for soft-pedaling or omitting incidents of money laundering in reports to regulators.

Top executives at the firms have been shown to be taking a cavalier attitude: A congressional investigation revealed a PWC managing director e-mailing his colleagues about a controversial tax arrangement for Caterpillar, “What the heck. We’ll all be retired when this … comes up on audit. … Baby boomers have their fun, and leave it to the kids to pay for it.”

Later, he characterized it as an “attempt at humor.”

What is to be done

The problem is exacerbated by the revolving door—most of the people who truly understand these complex accounting arrangements drift back and forth between the private sector and the government agencies that regulate them. Nonetheless, tax-starved governments have begun cracking down on these arrangements, focusing on the standards used to determine how much tax companies can avoid with these corporate structures.

While Juncker’s connection to these latest documents may tarnish the EC’s investigation, the OECD, a policy-coordinating group for wealthy nations, is developing new standards that may be stricter.