US president Barack Obama and Chinese president Xi Jinping announced a joint agreement to reduce carbon emissions today in Beijing. Under terms of the deal, the US pledged to more than double its reduction in greenhouse gas emissions between 2020 and 2025, for a total reduction of 26-28% below 2005 levels. And China promised that its emissions would peak “around” 2030, and that 20% of the country’s energy would come from emission-free sources by then.

Negotiations for the agreement reportedly involved nine months of secret talks, including a letter from Obama to Xi proposing the deal. It was quickly hailed in press accounts as “ambitious,” “surprise move,” and a “major breakthough.“

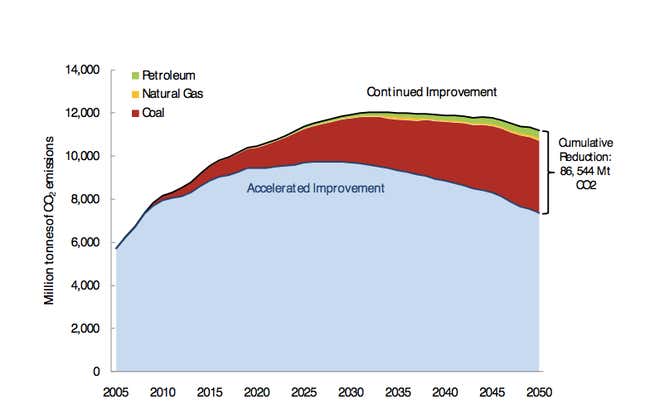

Pinpointing a 2030 target for peak carbon emissions is definitely a first for China. But, as several China scribes pointed out, it isn’t exactly a stretch. In fact, 2030 is when analysts expected China’s emissions to peak anyway, even before Xi’s new energy policy announced this June:

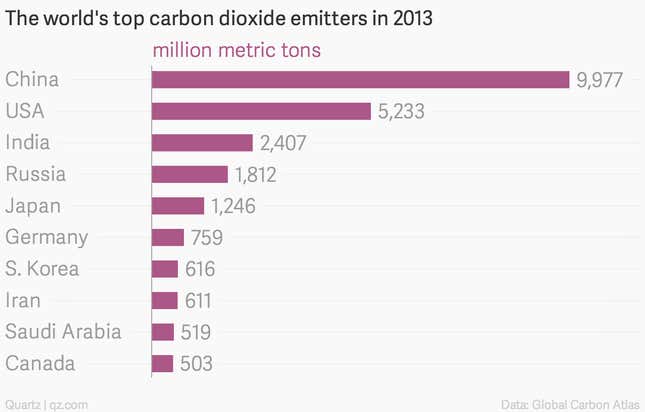

China is by far the world’s largest emissions producer, after overtaking the US as the largest emitter of greenhouse gasses in 2006, and this September passed the EU on a per capita basis, based on information from the Global Carbon Atlas:

Beijing has recently shown it is serious about cleaning up its emissions by strengthening environmental laws, toughening regulations, and stepping up oversight of factories and power plants. The tough new stance comes as choking pollution in cities like Beijing and rising health problems have led to widespread public outrage. Some sort of carbon cap from China has been anticipated for months.

While 2030 may not seem that ambitious, it is just an outside limit, the White House stressed, saying the US expects China “will succeed in peaking its emissions before 2030 based on its broad economic reform program, plans to address air pollution, and implementation of President Xi’s call for an energy revolution.”

The bigger challenge for China may be satisfying the pledge to get 20% of its energy from non-emissions producing sources. That promise will require, the White House says, “an additional 800-1,000 gigawatts of nuclear, wind, solar and other zero emission generation capacity”—an amount roughly equal to the entire US electricity capacity today.

But even that may not be a huge stretch. Based on China’s solar power push and incentives for alternative energy, one energy analyst predicted in June that 20% of China’s electricity could come from alternative sources by 2020.