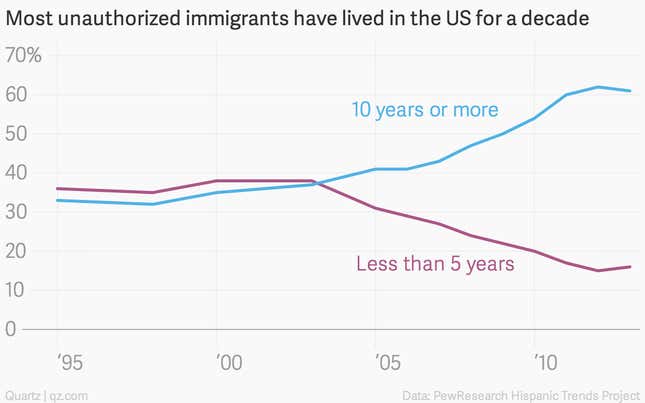

Angela Navarro, an unauthorized immigrant from Honduras to the US, has been in the news for seeking refuge in a Philadelphia church to avoid deportation, which would take her away from her husband and children, all US citizens. She has something in common with most other unauthorized immigrants: She’s lived in the US for more than a decade.

Tonight, US president Barack Obama will announce that he is allowing more than 5 million unauthorized immigrants to work legally in the United States if they have no criminal record and have lived in the country for five years.

His decision comes after House Republicans killed a bipartisan immigration reform bill passed by the Senate last year. The last attempt at comprehensive immigration reform failed in 2007; the most recent overhaul was accomplished in 1986. So the president argues that he needs to use his executive powers to act—in part because, even as unauthorized immigration into the US has slowed, the existing unauthorized population isn’t going anywhere.

Indeed, the median length of time that unauthorized immigrants have been living in the US is almost 13 years. Most experts don’t think it’s possible, even if the US wanted to spend billions and alienate everyone from big business to the religious community, to deport all these migrants, who make up one in 20 US workers.

But without legal certainty, immigrants live in fear of having their families broken up, and cannot contribute to the US economy as fully as they might otherwise; it’s a stalemate that serves neither side. Obama had hoped the 2013 compromise reached in the Senate would give the unauthorized population a statutory path to legal residence in exchange for even more militarized border security and visas for new, highly-skilled workers; but the House hasn’t voted on the bill, and most analysts expect very little legislation to be produced before the next president comes into office in 2017.

Absent a compromise, Obama, like presidents George H. W Bush and Ronald Reagan before him, will turn to executive action as way to rectify the impasse. Opponents of his use of prosecutorial discretion to protect unauthorized immigrants have said his move will poison the well for further negotiations with Congress. But after years of waiting for immigration reform, it’s hard not to see Obama’s move as a catalyst for Congressional action.