Back at the start of the current American football season, the US’s favorite game was on its knees, mired in a series of unprecedented scandals.

Consider September alone: Elevator footage surfaced showing a player, Ray Rice, knocking his wife unconscious. The National Football League’s top executive held a disastrous press conference denying he had responded inadequately to the incident. Another player was indicted for allegedly striking a child with a tree branch. And the NFL made its most candid admission, in court documents obtained (paywall) by the New York Times, that up to one third of its players sustain serious brain damage.

It felt like the tide of popular opinion was finally beginning to turn against the sport. Even advertisers were starting to get nervous.

Yet here we are, on the eve of another Super Bowl. A record TV audience is expected for the game on Sunday (Feb. 1); a record advertising haul is all but confirmed. The scandals feel almost forgotten (although the league will air a public service announcement about domestic violence during the game). A somewhat frivolous scandal about deflated game balls is getting much more attention.

Last week, the latest edition of a long running survey by Harris Interactive found that football remains easily America’s most popular sport. If the scandals of recent months won’t turn people against it, then maybe nothing can.

Then again, history is littered with implosions of great empires that no-one saw coming. What if the NFL’s commercial dominance is just a mirage?

Demography is destiny

“I’m a big football fan, but I have to tell you if I had a son, I’d have to think long and hard before I let him play football,” President Obama famously told the New Republic in 2013. It seems many Americans agree. A survey by Bloomberg last month found that half of them wouldn’t want their sons playing the sport.

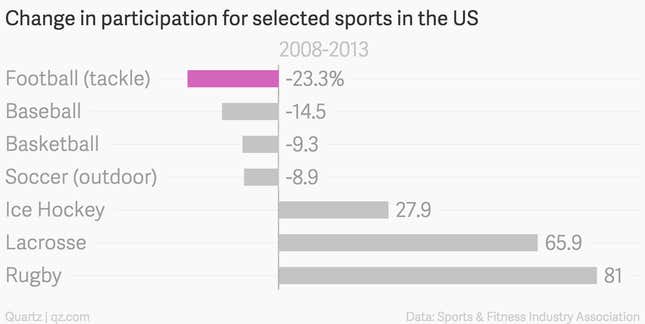

Participation has been waning for years. Between 2008 and 2013 the number of people playing tackle football, the full-contact version of the sport, declined by 1.9 million people, a drop of 23%, according to the Sports Industry and Fitness Association. There has even been an exodus from safer variants like “flag” football (down 21%) and touch football (down 32%).

The decline, which doesn’t even take into account the travails of 2014, was much sharper, in percentage terms, than the falls experienced by football’s two closest rivals in overall popularity, baseball and basketball.

American football also suffered a steeper player decline (in both percentage and absolute terms) than soccer, the world game that is starting to make serious inroads in the US.

The exodus from tackle football contrasts markedly with growth in other notably violent games like rugby, lacrosse and ice hockey.

It might be that football is losing participants to these sports. But they’re not a serious threat to it. Rugby and lacrosse remain niche and largely amateur activities (in the US at least, for rugby). Ice hockey is already established as a pro sport, but suffers from its own concerns about violence and concussions.

It’s also questionable whether participation numbers are really the best way to measure the health of football relative to other games. Football is, after all, a complicated game, typically played in highly organized settings, largely by elite athletes; other sports are much more conducive to social and casual play, and have long had bigger participation bases.

Still, if participation in tackle football keeps shrinking at its current rate, at some point there will be no one left to play it.

This is the bleak future the author Malcolm Gladwell envisages. In a 2009 essay for the New Yorker he famously compared football to dogfighting. More recently, he controversially said the sport will become ”ghettoized”, like joining the army—something done only by people who have few other options and don’t understand or are willing to take on the health risks.

Last year Gladwell reaffirmed his belief that football will eventually implode. ”We’re talking about brain injuries that are causing horrible, protracted, premature death,” he told Bloomberg. “This… is appalling. Can you point to another industry in America which, in the course of doing business, maims a third of its employees?”

If history is any guide…

Other sports that were once mainstream in the US, like boxing and horse racing, have fallen out of favor too. Yet the decline of those two pastimes arguably has less to do with the worries about brain damage (in boxing) or animal cruelty (in horse racing) than with maladministration.

Boxing has been plagued by corruption and stifled by bureaucracy. There are so many competing titles that the general public does not know who the best fighters are, and organizing match-ups between the ones they might know about is also proving nigh-on impossible. Corruption is a problem in horse racing too; the flight to the suburbs, and the rise of alternate forms of gambling are among the other factors (paywall) that have contributed to its decline.

But perhaps the single biggest reason why both boxing and horse racing fell out of the mainstream in the US is that, unlike football, they failed to harness the power of television. Boxing’s big fights are typically pay-per-view events which can cost a viewer a one-off fee upwards of $60, putting them out of reach for many people. And with the exception of one or two of the biggest events, horse racing in the US is marooned in the backwaters of cable.

Football: the ultimate TV sport

In contrast, football is perfectly made for television. Its spectacular athleticism, gladiatorial brutality and chess-like strategy appeal to Americans in the same way that Hollywood blockbusters do. And they work well across the full gamut of television formats, from epic drama (the average NFL game lasts over three hours) to six-second clips that go viral on social media:

This explains football’s ability to draw huge audiences at a time when viewership for almost everything else is fragmenting. This year’s Super Bowl may break last year’s record as the most watched telecast ever in the US. The three most watched broadcasts in the history of US cable TV all took place earlier this month. They were all college football games on ESPN.

Football is also—more than any other sport—perfectly tailored for advertising, since a game famously contains lots of stoppages, providing ample opportunities for commercial breaks. And blue-chip advertisers can’t get enough of it. In September, when there was serious talk of a consumer boycott of the NFL for its handling of the Ray Rice case, brewing giant Anheuser-Busch sounded a warning to the league. “We are not yet satisfied with the league’s handling of behaviors that so clearly go against our own company culture and moral code,” it said. Other sponsors like Pepsi and McDonald’s voiced similar concerns.

But no-one ceased advertising. This Sunday, the SuperBowl will attract 15 first-time advertisers, the most since 2000. And 30- and 60-second ad spots will command record rates.

The court of popular opinion

This chart probably explains why the advertisers didn’t bolt.

The consumer perception of the NFL plummeted as the Ray Rice scandal took hold, research from YouGov, a market-research agency, shows. But as the season wore on, people seemed to forget or blank out the off-field drama and started to focus on the games again. After a few classic playoff matches, the NFL’s perception had rebounded sharply (although YouGov points out, it’s well below where it was this time a year ago).

Football has become so important to the TV industry and so perfect a vehicle for advertisers that you get the feeling that it would take something truly, unfathomably catastrophic for it to to collapse. Michael Lewis, an associate professor of marketing at Emory University, compares America’s fervent support for football to partisan politics. “Look at people who identify as Republicans or Democrats and how they react to a scandal within their own party,” he tells Quartz. “There are some folks for the current president, it doesn’t matter what he does, Obama is going to be their guy. It’s exactly what would have happened with George Bush a decade ago.”

According to Lewis, the NFLs brand is almost unbreakable. But not completely. ”I think the only way the NFL could find itself in a problem is if something happened to the on-field product,” he says. “Something meaningful, a corruption of the game.” An endemic match-fixing problem, or widespread performance-enhancing drug abuse, perhaps.

Derek Thompson, from our sister site The Atlantic, has a completely unscientific, yet still compelling alternative theory about what might be going on. He thinks the league might be accumulating invisible damage, which at some point, might cause it to collapse. “You can’t see football’s moral disintegration if you just look at the numbers,” he recently wrote. “But that doesn’t prove that fans don’t care. Maybe they’re just starting to think.”

The endgame

American football has experienced at least one serious existential crisis before. In 1905, amid repeated deaths and rising unrest over player safety, then president Teddy Roosevelt convened a summit at the White House to make it safer. But those were different days, when government was more trusted. It’s hard to imagine today’s administrations intervening in something that’s both a national pastime and a massive industry.

It seems blindingly obvious to an outsider like me (I did not grow up in the US) that the very equipment designed to protect players—helmets—are a big part of the on-field violence problem. They give players a false sense of security, and are even used as weapons (as players charge into each other head first, rather than tackle with arms and shoulders). There are signs that this might someday be addressed: The NFL has been looking at ways to make helmets more shock-absorbent, and various researchers are looking at other ways to make them safer. Yet if Lewis’s analogy with partisan politics is correct, then maybe that won’t happen. Doing so might be the NFL equivalent of a Republican raising taxes.

If safety doesn’t improve, one way football could decline is if both pro and college football are swamped by lawsuits. Eventually, the game could become uninsurable, and the economics will no longer stack up. (This scenario was explored by the economists Kevin Grier and Tyler Cowen for Grantland in 2009). Or perhaps it will become “ghettoized”, as Gladwell put it, advertisers will retreat, and it will all come crashing down. Maybe the glaring lack of appeal of football outside of the US will prove its Achilles heel; or maybe, as Mark Cuban, the media magnate and basketball team owner has suggested, over-saturation in the US will be its undoing.

Maybe.

In any case, if like millions of Americans, you tune into NBC on Sunday evening to watch the big game, to see Katy Perry performing during halftime, or even for the commercials, the idea that football could fall off the map anytime soon will seem far-fetched, at best.