For many years, the story of Monopoly’s origins began with a man during the Great Depression. However, the game actually dates back to a left-wing woman, Lizzie Magie, who received a patent for her Landlord’s Game back in 1904. In this excerpt from her book “The Monopolists,” Mary Pilon explains who Magie was and what she was trying to say with her revolutionary game.

To Elizabeth Magie, known to her friends as Lizzie, the problems of the new century were so vast, the income inequalities so massive, and the monopolists so mighty that it seemed impossible that an unknown woman working as a stenographer in Washington, D.C., in the early 1900s stood a chance at easing society’s ills with something as trivial as a board game. But she had to try.

Night after night, after her work at the office was done, Lizzie sat in her home, drawing and redrawing, thinking and rethinking. She wanted her board game to reflect her progressive political views—that was the whole point of it—which centered on the economic theories of Henry George.

A charismatic nineteenth-century politician and economist who had passed away just a few years before, George had been a proponent of the “land value tax,” also known as the “single tax.” His main tenet was that individuals should own 100 percent of what they made or created, but that everything found in nature, particularly land, should belong to everyone.

George’s message had resonated deeply with many Americans in the late 1800s, when poverty and squalor were on full display in the country’s urban centers. Poor immigrants and natives alike were packed tightly together in noxious slums, where they slaved long hours in dirty, dangerous factories, earning little more than a pittance. The single-taxers believed that if all taxes were eradicated except for the one on property, and the poor and the working class were able to keep more of their hard-earned dollars, poverty levels would quickly diminish.

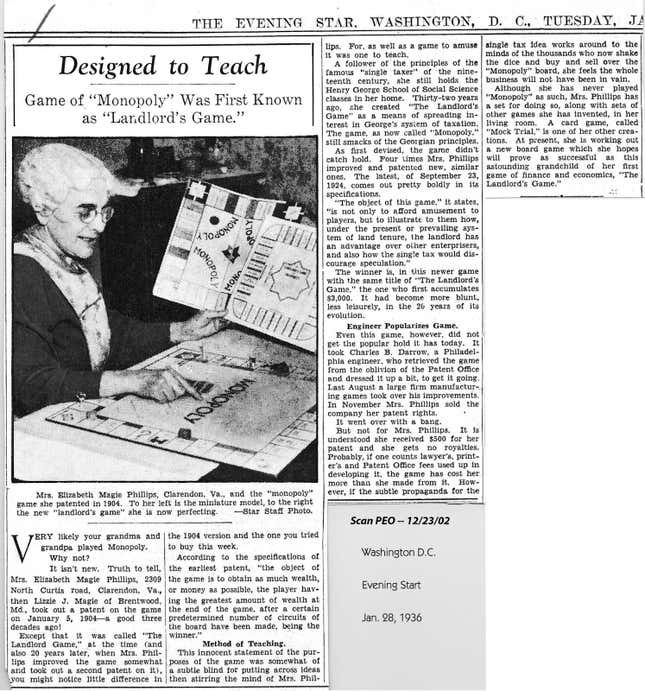

Among his impassioned followers was Lizzie, a distinctive-looking woman in her thirties, with curly dark locks and bangs that framed her face, Lizzie had inherited the bushy eyebrows of her father. The descendant of Scottish immigrants, she had pale skin, a strong jawline, and a strong work ethic. As she aged, she took to wearing her long, wavy hair in a bun, which accentuated her finely etched features.

In the early 1900s, Lizzie was unmarried, unusual for a woman of her age at the time. Even more unusual, however, was the fact that she was the head of her household. Completely on her own, she had saved up for and bought her home, along with several acres of property.

She lived in Prince George’s County, a Washington, D.C., neighborhood where the residents on her block included a dairyman, a peddler who identified himself as a “huckster,” a sailor, a carpenter, and a musician. Lizzie shared her house with a male actor who paid rent and a black female servant.

Lizzie’s anti-monopoly political views had been influenced, albeit indirectly, by Abraham Lincoln. In 1858, before she was born, Lizzie’s father, James Magie, accompanied Lincoln and Joseph Medill, the thirty-five-year-old publisher of the Chicago Tribune, as the lanky lawyer traveled around Illinois debating politics with Stephen Douglas.

When Lizzie was thirteen, her family suffered significant financial losses, probably due to the Panic of 1873, which had started six years earlier and was still having repercussions. It was triggered by several causes, including a fall in silver prices, railroad speculation, a trade deficit, property losses, and a general economic malaise tied to the Franco-Prussian War. Lizzie had to leave school to help support her family, a fact that she lamented long into her adulthood.

She attended a convention of stenographers with her father and soon found work in that field. At the time, stenography was a growing profession, one that had opened up to women as the Civil War removed many men from the workforce. The typewriter was gaining commercial popularity, leaving many to ponder a strange new world, one in which typists sat at desks, hands fixed to keys, memorizing seemingly illogical arrangements of letters on the new QWERTY keyboards.

Lizzie’s father also shared with his daughter a copy of Henry George’s bestselling 1879 tome, Progress and Poverty. The early seeds of what would later evolve into one of the most popular modern board games of all time had been planted.

“I have often been called a ‘chip off the old block,”’ Lizzie said of her relationship with her father, “which I consider quite a compliment, for I am proud of my father for being the kind of an ‘old block’ that he is.”

Lizzie found work as a stenographer and typist for the chief clerk of the Dead Letter Office, the receptacle for the nation’s undeliverable mail. Sometimes letters found their way to the office because of lousy penmanship. Other times there was no address at all. Prank letters arrived, senders unknown.

The Dead Letter clerks, many of them women, were responsible for sorting lost envelopes and parcels, and for disposing of the unclaimed mail, either by destroying it or by auctioning off its contents. The clerks also tallied up any enclosed money and handed the funds over to the U.S. Treasury. Only workers in the Dead Letter Office had the authority to open the mail, and some became lay detectives. Through their work, stories emerged of mothers reunited with lost sons and employees at last collecting long-missing paychecks.

In the evening after work, Lizzie pursued literary ambitions, writing poetry and short stories, and, as a player in Washington’s nascent theater scene, performed on the stage, where she earned praise for her comedic roles. Though small-framed and only in her twenties, she had a presence—the audience at the Masonic Hall exploded with laughter at her comical rendition of a simpering old maid. She also sometimes took on male roles. “She wants to fly,” James said of his daughter, “but hasn’t got the wings.”

On January 3, 1893, Lizzie went to the U.S. Patent Office to lay legal claim to her invention. As a woman, she would have been a standout in that office at any age, but at twenty-six, she was a phenomenon.

Four years later, Lizzie’s story “The Theft of a Brain: The Story of a Hypnotized Novelist and a Cruel Deed” was published in Godey’s, a women’s magazine based in Philadelphia. An important platform for men and women thinkers, Godey’s had published authors such as Frances Hodgson Burnett, Washington Irving, and Edgar Allan Poe.

“The Theft of a Brain” was about an aspiring novelist named Laura Lynn, who said to a friend that if she could write something that every- body read, she would be “perfectly happy.” Laura was talented and passionate, and her real difficulty was a lack of confidence. She sought out a professor, who hypnotized her into writing. Under hypnosis, she wrote a story titled “Privileged Criminals,” about a woman who was convicted of a crime she hadn’t committed. When Laura woke up, the professor told her that she had become a successful writer who was selling her short stories for five hundred dollars each. Laura was elated. She continued to write short stories for some time and then wrote a novel. But when she tried to publish the novel, she found that a plagiarized copy already existed and had become a bestseller. The plagiarist was none other than the hypnotist professor.

“I stole the brains of other undeveloped geniuses,” he confessed.

The plotline that Lizzie had created would soon hold eerie parallels to her own life.